In 1977, archaeologists excavating the Bronze Age cemetery of Shahr-i Sokhta in southeastern Iran unearthed an extraordinary relic: a 4,500-year-old board game buried in a richly adorned grave. This game, consisting of a board with 20 circular spaces formed by a carved snake design, 27 geometric pieces, and four dice, has captured the imagination of researchers for decades. Now, modern tools and cross-disciplinary analysis are shedding light on how this ancient pastime might have been played.

Shahr-i Sokhta, meaning “Burnt City,” is a significant archaeological site in southeastern Iran, dating back to the Bronze Age (3rd millennium BCE). Located near the Helmand River in the Sistan-Baluchestan province, it was a flourishing urban center of the Helmand culture, known for its advanced craftsmanship, trade networks, and early urban planning.

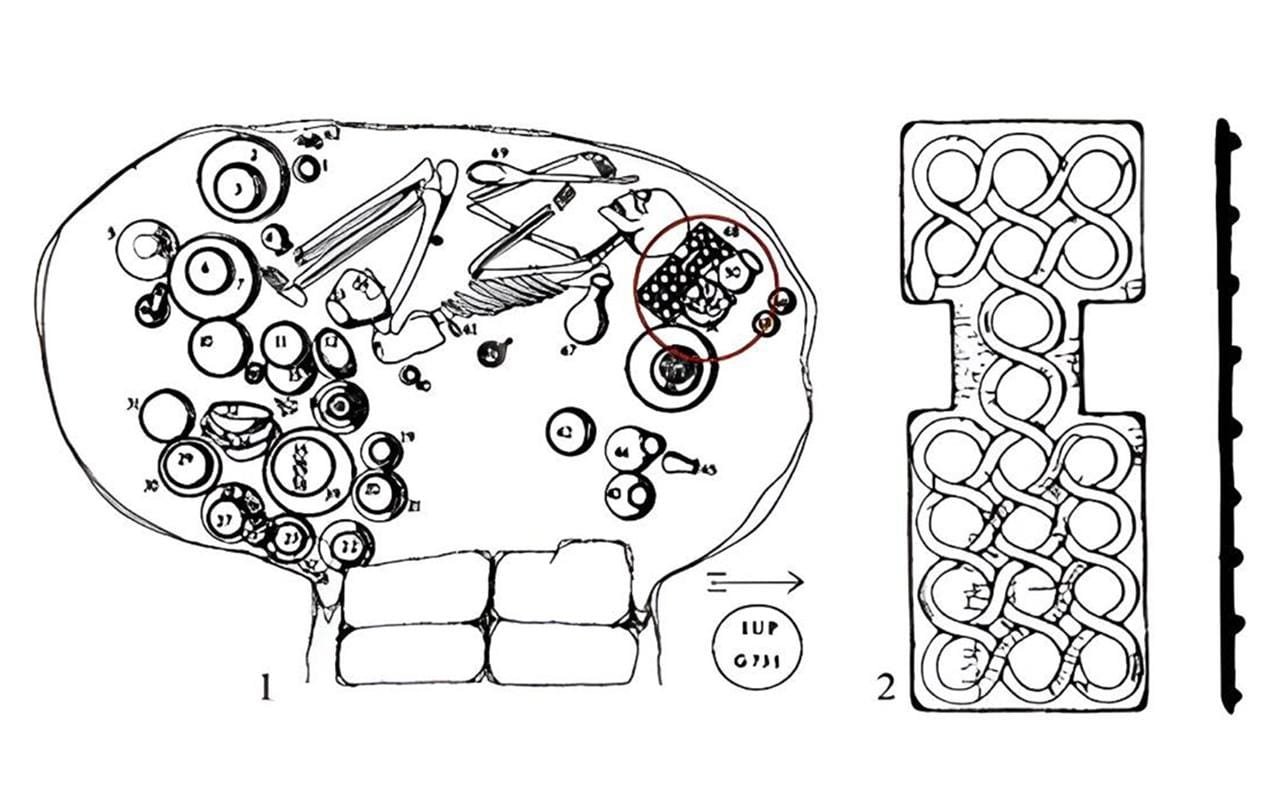

Excavations have revealed remarkable finds, including an artificial eye and intricate jewelry. Grave No. 731 yielded the complete board game, one of the oldest ever discovered, dating back to approximately 2600–2400 BCE. This treasure stands alongside other iconic ancient games such as Senet from Egypt and the Roman Ludus Latrunculorum.

Unlike the Royal Game of Ur from Mesopotamia—whose rules were deciphered from a cuneiform tablet in the British Museum—no written instructions for the Shahr-i Sokhta game have survived. Researchers thus turned to a combination of archaeological evidence, historical comparisons, and modern computational tools to reconstruct plausible gameplay.

The Shahr-i Sokhta board game appears to be a strategic racing game akin to the Royal Game of Ur, though with added complexity. According to researchers, the game’s objective is to move all 10 of a player’s pieces off the board before the opponent does, using a combination of dice rolls and strategic placement of “blocker” and “runner” pieces.

“The core gameplay revolves around racing, with blocker pieces introducing additional strategy without overshadowing the runners,” explained the research team in their study, soon to be published in the Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies. Players use dice to advance their pieces, and special rules allow strategic movements for the blockers, which can hinder the opponent’s progress.

The researchers hypothesize that the game’s additional pieces, including “star” pieces resembling rosettes found in the Ur game, added layers of complexity. Unlike Ur, the Shahr-i Sokhta game emphasizes a balance between strategy and chance, making it less repetitive and more engaging for players. The game was tested by 50 experienced players, who evaluated its gameplay and compared it to the Royal Game of Ur.

Modern AI techniques are further aiding the understanding of ancient games. By simulating thousands of potential rulesets, AI algorithms help determine which rules result in enjoyable gameplay. The Shahr-i Sokhta game has also benefited from computational modeling, which confirms its superiority in strategic depth compared to the simpler Royal Game of Ur.

The discovery and analysis of the Shahr-i Sokhta game deepen our understanding of how board games evolved in the ancient world. Unlike the Ur game, which was associated with Mesopotamian royalty, the Shahr-i Sokhta game was found in a wealthy but non-royal grave, suggesting it was more accessible and widespread in eastern regions.