The origins of syphilis, a sexually transmitted infection that devastated Europe during the late 15th century, have puzzled researchers for decades. A new study, published in Nature, provides groundbreaking insights into the debate over whether the disease originated in the Americas or existed in Europe before the voyages of Christopher Columbus. Drawing on ancient DNA from archaeological remains across the Americas, the study strongly supports the hypothesis that syphilis and its related diseases have deep roots in the Americas.

The first recorded syphilis epidemic swept across Europe in the aftermath of King Charles VIII of France’s invasion of Naples in 1494. Known for its disfiguring symptoms and high mortality rate, the disease rapidly spread across the continent. At the time, it was called by various names, including the “French disease” by Italians and the “Neapolitan disease” by the French, reflecting the tendency to blame neighboring nations for outbreaks.

The epidemic occurred shortly after Columbus and his crew returned from the Americas, fueling speculation that the disease was introduced to Europe through transatlantic contact. This theory, known as the “Columbian hypothesis,” posits that syphilis originated in the Americas and was brought to Europe by the early explorers. However, an opposing theory suggests that syphilis had existed in Europe earlier but became more virulent in the late 15th century.

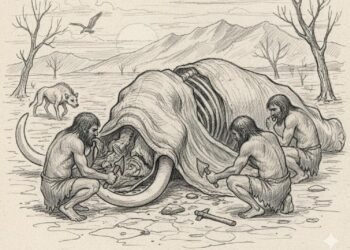

The new study, led by Kirsten Bos and Johannes Krause of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, analyzed ancient DNA from skeletal remains in Mexico, Peru, Argentina, and Chile. Using state-of-the-art paleopathology techniques, the researchers reconstructed five genomes of Treponema pallidum, the bacterium responsible for syphilis and its related diseases, yaws and bejel. These genomes date back as far as 9,000 years, predating Columbus’s voyages.

“We’ve known for some time that syphilis-like infections occurred in the Americas for millennia, but from the lesions alone, it’s impossible to fully characterize the disease,” explained Casey Kirkpatrick, a postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute. The genomic analysis revealed that T. pallidum originated in the Americas during the middle Holocene epoch and subsequently diversified into the subspecies responsible for treponemal diseases today.

Dr. Kirsten Bos stated: “The data clearly support a root in the Americas for syphilis and its known relatives. Their introduction to Europe, which started in the late 15th century, is most consistent with the evidence.” The study further suggests that the global spread of syphilis was facilitated by transatlantic human trafficking and European colonial expansions.

While the study provides compelling evidence for an American origin of syphilis, it does not settle all debates. Skeletal remains in Europe exhibiting syphilis-like lesions that predate 1492 challenge the Columbian hypothesis. “The search will continue to define these earlier forms, and ancient DNA will surely be a valuable resource,” said Johannes Krause, co-author of the study. He added, “Who knows what older related diseases made it around the world in humans or other animals before the syphilis family appeared.”

The study underscores the interconnectedness of human history and disease. Indigenous populations in the Americas harbored early forms of syphilis and related diseases long before European contact. “While indigenous American groups harbored early forms of these diseases, Europeans were instrumental in spreading them around the world,” Bos remarked. The European expansion not only carried syphilis to new regions but also subjected indigenous communities to devastating epidemics of foreign diseases like smallpox.

OMG! This fact has been known for at least 100 years and no recent study was needed to confirm it. Europeans took syphilis back to Europe well befor colonization began. It killed millions in the first two years, since they had no natural immunity. Native Americans got yellow fever in return.

While this idea has been part of public discourse for many years, the purpose of scientific disciplines like archaeology is to provide evidence-based conclusions. Popular beliefs or assumptions, no matter how widespread, need to be tested and verified through rigorous research. Science doesn’t rely on hearsay or assumptions.

Smh another article about blaming the White man for EVERYTHING, how did it start in America before the White man came to America? The evil racist White man brought it to America, liberal logic 🤦🏻♀️ everyone hate colonialism but everyone enjoys the fruits of colonizers.

It’s not blame.

Every germ mutates. It’s just this one might ( HYPOTHESIS) have developed in the americas

I see the centuries old moral implications of disease is still with us. Shame

I wish you would update the title of the article to include HYPOTHESIS

this article is being shared on social media. And people are unfortunately only reading the title

I KNOW it is in the 1st paragraph but these are the times we are in. Reading comprehension is very low

And titles are what people read

Thank you.