Since the early days of archaeology, women have played a crucial role, making substantial and pioneering strides within the field. In fact, some of the discipline’s most significant early developments were forged by women.

Although some of their contributions date back more than a century, their work is less well known. Nonetheless, the archaeology domain has progressed, with women now constituting roughly half of all archaeologists.

This article aims to spotlight notable and trailblazing women archaeologists from the field’s nascent stages. These extraordinary individuals demonstrated determination and fearlessness in their quest to push the boundaries of archaeological exploration in innovative directions.

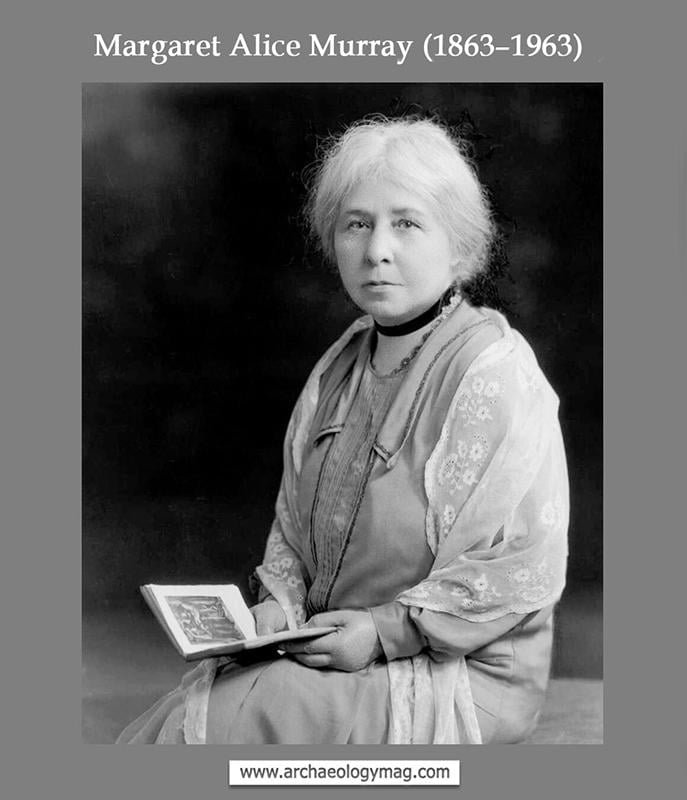

1- Margaret Alice Murray (1863–1963)

Margaret Murray was an Egyptologist, archaeologist, anthropologist, historian, and folklorist of Anglo-Indian origin. She was born on July 13, 1863, in Calcutta, India.

Margaret Murray was an Egyptologist, archaeologist, anthropologist, historian, and folklorist of Anglo-Indian origin. She was born on July 13, 1863, in Calcutta, India.

She later moved to England and was the first woman to be appointed as an archaeology lecturer in the United Kingdom.

From 1898 to 1935, she worked at UCL and served as President of the Folklore Society from 1953 to 1955. She also participated in larger social movements of the time, particularly the campaign for women’s suffrage.

Margaret Murray participated in excavations in Egypt (1902-4), Malta (1921-24), Hertfordshire, England (1925), Minorca (1930-31), Petra (1937), and Tell Ajjul, South Palestine (1938).

She is best known for her controversial witchcraft books. In The Witch Cult in Western Europe (1921), Murray proposed the idea that witchcraft was a pre-Christian religion in its own right, rather than a heretical aberration from established Christianity.

She died November 13, 1963, soon after her hundredth birthday.

2- Gertrude Caton-Thompson (1888–1985)

Gertrude Caton-Thompson was an archaeologist from England. She was born in 1888 in London. When she was five years old, her father died, leaving her with financial stability.

Gertrude Caton-Thompson was an archaeologist from England. She was born in 1888 in London. When she was five years old, her father died, leaving her with financial stability.

Her archaeological work was mostly done in Egypt. However, she also worked on expeditions in Malta, Zimbabwe, and South Arabia.

Her interest in archaeology began with a trip to Egypt with her mother in 1911, followed by a series of lectures by Sarah Paterson at the British Museum on Ancient Greece. As a result, she decided to volunteer as a “bottle washer” at an excavation site. This was her first experience of archaeological work.

She was an archaeologist at a time when participation by women in the discipline was uncommon. Her notable contributions to archaeology include developing a technique for excavating archaeological sites and information on Paleolithic to Predynastic civilizations in Zimbabwe and Egypt. She was a member of many organizations, such as the Prehistoric Society and the Royal Anthropological Institute.

After the Second World War, Caton Thompson retired from fieldwork. In 1983, she published her memoirs as an autobiography titled “Mixed Memoirs.” She died in her 97th year at Broadway, Worcestershire, in 1985.

3- Dame Kathleen Kenyon (1906–1978)

Dame Kathleen Kenyon, in full Dame Kathleen Mary Kenyon, was a British archaeologist who specialized in Neolithic culture in the Fertile Crescent.

Dame Kathleen Kenyon, in full Dame Kathleen Mary Kenyon, was a British archaeologist who specialized in Neolithic culture in the Fertile Crescent.

She educated at Somerville College, Oxford. She is best known for her fieldwork in Sabratha (Tripolitania), Jericho, Jerusalem, etc.

Dame Kathleen Kenyon excavated Jericho to its Stone Age foundation, proving it to be the oldest continually occupied human settlement yet discovered. She also led excavations at Tell es-Sultan, the ancient Jericho site, from 1952 to 1958.

She was initially appointed as a Trustee of the British Museum for an eight-year term beginning on June 12, 1965, but this was subsequently renewed; she finally retired as a Trustee on May 20, 1978.

From 1962 to 1973, she was the Principal of St Hugh’s College, Oxford. Kenyon was also the Honorary Vice President of the Chester Archaeological Society.

The Kathleen Kenyon Archaeology Collection, which was purchased from Kenyon’s estate in 1984, is kept at Baylor University in Waco, Texas.

The finds from her excavations are housed in a number of collections, including the British Museum, the UCL Institute of Archaeology, while the bulk of archive material is located at the Manchester Museum.

Kenyon has been called one of the twentieth century’s most influential archaeologists.

4- Gertrude Bell (1868–1926)

Gertrude Margaret Lowthian Bell was an archaeologist, writer, traveler, and political officer from England.

Gertrude Margaret Lowthian Bell was an archaeologist, writer, traveler, and political officer from England.

She was born into a rich family in Washington New Hall, County Durham. She was home-schooled at first, then went to school in London, eventually earning a first-class pass in Modern History (degree equivalent) at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford.

She then traveled throughout Europe and spent time in Bucharest and Tehran. Her travels continued with two round-the-world trips, one in 1897-1898 and the other in 1902-1903.

Gertrude developed an interest in Arab peoples around the turn of the century, learning their languages, researching their archaeological sites, and traveling deep into the desert. During the First World War, her intimate knowledge of the country and its tribes made her a target for British Intelligence recruitment.

Because of her extensive travels in Syria-Palestine, Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, and Arabia, she became a highly influential to British imperial policy-making. S he founded the Iraq Museum in Baghdad, as Honorary Director of Antiquities in Iraq.

Bell wrote voluminously during her life. She translated a book of Persian poetry, wrote several books about her travels, adventures, and excavations, and sent a steady stream of letters back to England during World War I that influenced government thinking at a time when few English people were familiar with the contemporary Middle East.

5- Dorothy Garrod (1892–1968)

Dorothy Annie Elizabeth Garrod was an English archaeologist who specialized in the Paleolithic period. She held the position of Disney Professor of Archaeology at the University of Cambridge from 1939 to 1952 and was the first woman to hold an Oxbridge chair.

Dorothy Annie Elizabeth Garrod was an English archaeologist who specialized in the Paleolithic period. She held the position of Disney Professor of Archaeology at the University of Cambridge from 1939 to 1952 and was the first woman to hold an Oxbridge chair.

She broke barriers again and again from how archaeology was done to who could do it. Her contributions to the archaeological community are truly unprecedented giving archaeologists the tools to continue their work in the present and the future.

Garrod carried out Paleolithic, or Old Stone Age, research in Gibraltar (1925–26) and in southern Kurdistan (1928). She also directed excavations at Mount Carmel, Palestine (1929–34), which brought to light the first evidence of Paleolithic and Mesolithic, or Middle Stone Age, cultures in Palestine. She turned to Stone Age studies in Bulgaria in 1938.

Dorothy Garrod was a leading authority on the Paleolithic for many years. She is undoubtedly one of the most influential archaeologists of her time.

6- Harriet Boyd Hawes (1871–1945)

Harriet Ann Boyd Hawes was an American archaeologist, nurse, and relief worker best known for discovering ancient remains on the Aegean island of Crete.

Harriet Ann Boyd Hawes was an American archaeologist, nurse, and relief worker best known for discovering ancient remains on the Aegean island of Crete.

Harriet Boyd was first introduced to the study of Classics by her brother. She graduated with a degree in Classics (specializing in Greek) from Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, in 1892, and then taught ancient and modern languages for four years, first as a private tutor in Henderson, North Carolina, and then at a girls’ school in Wilmington, Delaware. She enrolled in the American School of Classical Studies in Athens in 1896.

Having saved enough money to finance a trip to Crete, Boyd also visited the excavation at Knossos being worked by British archaeologist Arthur J. Evans, who suggested she explore the region around Kavousi. The discovery of Iron Age tombs there provided material for her master’s thesis; the degree was awarded to her by Smith College in 1901.

She had been an instructor in Greek archaeology, epigraphy, and modern Greek at Smith since 1900, and she retained the position until 1906. She was also the second person to have the honor of the Agnes Hoppin Memorial Fellowship bestowed upon her, and the very first female archeologist to speak at the Archaeological Institute of America.

Unlike many of her contemporaries, Hawes was more interested in the daily lives of the people she studied than in the gold, jewels, and palaces of the higher classes.

She not only made significant contributions to archaeology research, but she also broke down barriers in her male-dominated field, paving the way for future generations of female academics. She was a true pioneer of modern archaeological research.

7- Jane Dieulafoy (1851–1916)

Jane Dieulafoy was a French archaeologist, explorer, author, and journalist.

Jane Dieulafoy was a French archaeologist, explorer, author, and journalist.

She was born in Toulouse, France, to a wealthy family of bourgeoisie merchants. From 1862 until 1870, she studied at the Couvent de l’Assomption d’Auteuil in a Paris suburb. In May 1870, at the age of 19, she married Marcel-Auguste Dieulafoyare.

During the primary expedition, which they funded themselves, they crossed Iran from north to south on horseback, covering thousands of kilometers, to make a vast photographic inventory of Iranian patrimony; Jane took the photographs, thus putting together a record of exceptional quality for publications by Marcel and herself.

But she and her husband, are well-known for their excavations at Susa. The Susa mission was officially and financially supported by the Louvre and the Ministry of Public Instruction. They made numerous discoveries, some of which are on display at the Louvre.

In 1886, Jane Dieulafoy decorated of legion of honor.

8- Hetty Goldman (1881–1972)

Hetty Goldman was an archaeologist from the United States. She was the first woman faculty member at the Institute for Advanced Study and one of the first female archaeologists to conduct excavations in Greece and the Middle East.

Hetty Goldman was an archaeologist from the United States. She was the first woman faculty member at the Institute for Advanced Study and one of the first female archaeologists to conduct excavations in Greece and the Middle East.

She was born in New York City and was a Goldman Sachs banking family member. Goldman enrolled at Bryn Mawr College in 1899, where she majored in Classics and English. She continued study in Classics at Columbia University and worked as a manuscript reader after graduation.

In 1906, after a three-month tour of archaeological sites in Italy, she enrolled at Radcliffe College for graduate studies in classical languages and archaeology. Her master’s thesis on Greek vase painting helped her win the Charles Eliot Norton Fellowship to study at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens from 1910 to 1911. She was the first woman to hold the fellowship, and it was extended for a second year. In 1916, she received her PhD, having written a thesis entitled The Terracottas from the Necropolis of Halae.

Goldman became Professor Emerita in 1947. She was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1950. In 1966, she became the second recipient of the Archaeological Institute of America’s highest award, the Gold Medal for Distinguished Archaeological Achievement.

She died of pulmonary edema on May 4, 1972, in Princeton.

9- Tatiana Proskuriakova (1909–1985)

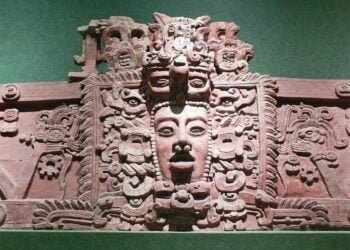

Tatiana Proskuriakova was a Russian-American Mayanist researcher and archaeologist who lived from 1909 to 1985. She made significant contributions to the decipherment of Maya hieroglyphs, the writing system of Mesoamerica’s pre-Columbian Maya civilization.

Tatiana Proskuriakova was a Russian-American Mayanist researcher and archaeologist who lived from 1909 to 1985. She made significant contributions to the decipherment of Maya hieroglyphs, the writing system of Mesoamerica’s pre-Columbian Maya civilization.

She was born in Tomsk, Russia’s Tomsk Governorate, and immigrated to the United States with her parents in 1916. She became an American citizen in 1924.

Proskuriakova enrolled at the Pennsylvania State College School of Architecture and graduated in 1930. She participated in two seasons of an archaeological expedition to Piedras Negras (Guatemala) in 1936-1937. In 1939, she made scientific expeditions to Copán and Chichen Itza.

She worked at the Carnegie Institute from 1940 to 1958, where she developed methods of dating ancient Mayan monuments based on the peculiarities of the fine arts style. She worked at the Mayapan excavations from 1950 until 1955. Proskouriakoff moved to Harvard University’s Peabody Museum in 1958, where she worked until her retirement in 1977.

Her paper “Historical Implications of a Pattern of Dates at Piedras Negras, Guatemala” was published in 1960. Her work helped provide the basis for Stuart’s breakthrough publication, “Ten Phonetic Syllables”, ushering in the now-accepted methodology of Maya hieroglyphic decipherable.

In her final years of life, she suffered from Alzheimer’s disease, and died on August 30, 1985; a tragic end for such a brilliant mind.

10- Theresa Bathsheba Goell (1901–1985)

Theresa Bathsheba Goell was an American archaeologist best known for leading excavations at Nemrud Dağı in Turkey’s southeast.

Theresa Bathsheba Goell was an American archaeologist best known for leading excavations at Nemrud Dağı in Turkey’s southeast.

She was born in New York and graduated from Radcliffe College with a BA. Her interest in archeological fieldwork began here. Goell went to England after graduating from Radcliffe, where she studied Newnham College in Cambridge and later studied in New York.

After her studies of architecture in Cambridge UK and archaeology in New York, she gained the necessary archaeological experience at the excavations at Tarsus in Cilicia, and from 1946 to 1949 she was the acting director of the excavations at Tarsus.

She made her first trip to Commagene and Nemrud Dağı in 1947. She was one of the first Western women to enter the mountainous Kurdish lands of south-eastern Turkey, and she faced many challenges. Excavations there would become her life’s work. Goell’s work in Turkey “nearly single-handedly opened up ancient Commagene to the world”.

She studied the tomb sanctuary from 1953 to 1973. Goell paid his final visit to Nemrud Dagh in 1973. She worked on the report on the Nemrud Dagh excavations until she had a stroke in 1983. She died on December 18, 1985, in New York City, after a long illness.

Her papers were given to Harvard University by her brother, which are now housed in the Schlesinger Library and Semitic Museum. Goell was posthumously awarded a master’s degree in 1990 for her work on Commagenian history.

11- Esther Boise Van Deman (1862–1937)

Esther Boise Van Deman was a prominent archaeologist in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. She was the first woman to specialize in Roman field archaeology and developed techniques for estimating the building dates of ancient Rome’s buildings.

Esther Boise Van Deman was a prominent archaeologist in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. She was the first woman to specialize in Roman field archaeology and developed techniques for estimating the building dates of ancient Rome’s buildings.

Esther Boise Van Deman was born in the state of Ohio. She was the youngest of six children. She graduated from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor with a bachelor’s degree in 1891 and a master’s degree in 1892. After teaching Latin in Massachusetts and Baltimore, Maryland, she received her Ph.D. in Latin from the University of Chicago in 1898. She then taught Latin at Mount Holyoke College (1898–1901).

After teaching at Mount Holyoke College, Van Deman went to Rome in 1901 to study at the American School of Classical Studies, which is now known as the American Academy in Rome. She was a Carnegie Institution fellow in Rome from 1906 to 1910, and a Carnegie Institution associate in Washington, D.C. from 1910 to 1925.

Van Deman discovered that the bricks blocking a doorway differed from those of the structure itself while attending a lecture in Rome’s Atrium Vestae in 1907, and showed that such differences in building materials provided a key to the chronology of ancient structures. Her preliminary findings were published in The Atrium Vestae by the Carnegie Institution (1909). Van Deman extended her research to other kinds of concrete and brick constructions, and in 1912, she published “Methods of Determining the Date of Roman Concrete Monuments” in The American Journal of Archaeology. Her basic methodology, with few modifications, became standard procedure in Roman archaeology.

Van Deman taught Roman archaeology at the University of Michigan from 1925 to 1930. She spent most of the rest of her professional life in Rome, where she died in 1937.

12- Edith Hayward Hall Dohan (1877–1943)

Edith Hall Dohan was one of the first American women in the field of archaeology. She graduated from Smith College in 1899 and went on to study archaeology and Greek at Bryn Mawr College, spending 1903-1905 at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens.

Edith Hall Dohan was one of the first American women in the field of archaeology. She graduated from Smith College in 1899 and went on to study archaeology and Greek at Bryn Mawr College, spending 1903-1905 at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens.

She joined Harriet Boyd Hawes and Richard Seager in excavating Gournia in Crete in 1904, from which she developed her PhD thesis, The Decorative Art of Crete in the Bronze Age, completed in 1907. In 1908, She received Bryn Mawr College’s first classical archaeology PhD.

From 1908 to 1912, she taught at Mount Holyoke College. In 1910 and 1912, she returned to two other archaeological sites in Crete, working under the auspices of the Penn Museum. In 1912, Dohan became the assistant curator of the Mediterranean Section at the Penn Museum.

After an interruption to start a family (1915–20), she returned to the museum, becoming its curator in 1942. She was the editor of the American Journal of Archaeology from 1932 to her death, specializing in Etruscan graves. She published an important corpus of Italic tomb groups held in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. In 1943, Dohan died unexpectedly at her desk.

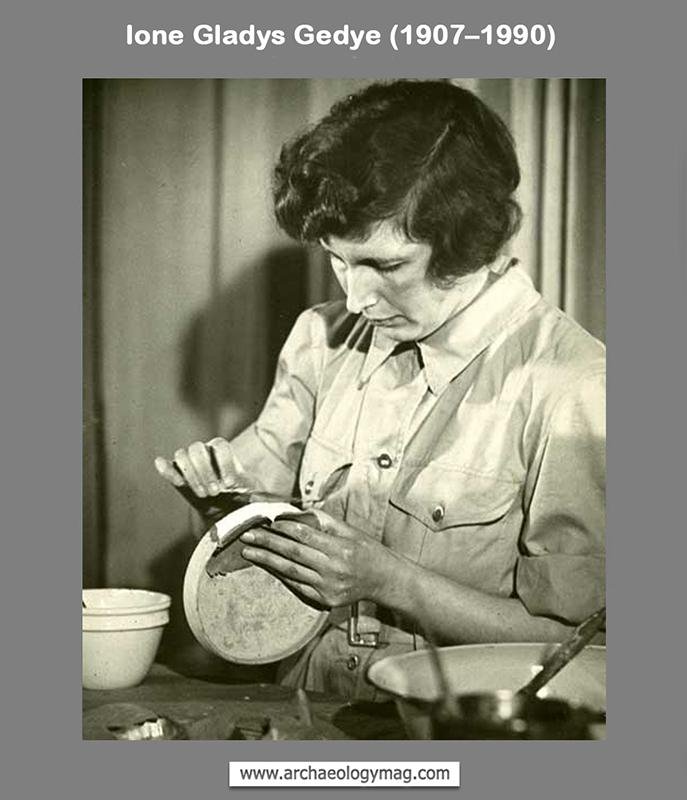

13- Ione Gladys Gedye (1907–1990)

Ione Gladys Gedye was a British conservator and archaeologist who founded the Repair Department at the Institute of Archaeology. She worked in conservation at the Institute for several decades and was a significant influence in the early years of archaeologically themed television programs.

Ione Gladys Gedye was a British conservator and archaeologist who founded the Repair Department at the Institute of Archaeology. She worked in conservation at the Institute for several decades and was a significant influence in the early years of archaeologically themed television programs.

Ione Gedye was the only daughter of civil engineer Lieutenant Colonel Nicholas George Gedye (1874-1947), of the Royal Engineers, OBE, and his wife Vera, daughter of Radclive’s John Thompson. Between 1918 and 1925, Gedye attended Francis Holland School, in Graham Terrace. She was a Flinders Petrie student and studied classical archaeology at University College London.

Gedye joined Tessa Verney Wheeler and Kathleen Kenyon in the Verulamium excavations. Wheeler had her clean up the excavations’ metalwork and encouraged her interest in artifacts.

She was one of the original staff members of the Institute of Archaeology’s technical department, which opened in 1937. She founded the Repair Department, which was initially housed in a former operating theater.

From 1937 to 1975, she taught conservation. In the late 1950s, Gedye was joined in her work by Henry W. M. Hodges, who helped her in developing the training course. Early broadcasts of archaeological digs by the BBC were informed by Gedye’s work. This work educated the public and contributed to the professionalization of archaeology in the United Kingdom.

Gedye retired in July 1975 and died in 1990. Every year, the UCL Institute of Archaeology bestows the Ione Gedye Award on the best conservation-based dissertation.