Scientists studying ancient diseases have discovered one of the earliest examples of zoonotic spillover, an event where a disease jumps from animals to humans, CNN reported.

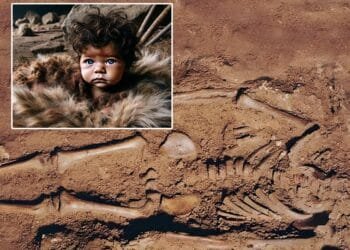

This significant revelation revolves around the fate of a Neanderthal man, believed to have fallen ill while butchering or cooking raw meat. The remarkable findings have emerged from a reexamination of the fossilized bones of the “Old Man of La Chapelle,” a Neanderthal whose remains were discovered in a cave near the French village of La Chapelle-aux-Saints in 1908.

Over a century later, these ancient bones continue to divulge new insights into the lives of Neanderthals, the robust Stone Age hominins that once inhabited Europe and parts of Asia before their mysterious disappearance approximately 40,000 years ago.

The Neanderthal in question, estimated to be in his late 50s or 60s at the time of his death some 50,000 years ago, displayed advanced osteoarthritis in his spinal column and hip joint, as confirmed by a study conducted in 2019.

However, a recent reanalysis led by Dr. Martin Haeusler, a specialist in internal medicine and the head of the University of Zurich’s Evolutionary Morphology and Adaptation Group at the Institute of Evolutionary Medicine, unveiled that not all the bone changes could be attributed to osteoarthritis-related wear and tear. Instead, they discovered signs of inflammatory processes.

According to Dr. Haeusler, “A comparison of the entire pattern of the pathological changes found in the La Chapelle-aux-Saints skeleton with many different diseases led us then to the diagnosis of brucellosis.”

Published in the journal “Scientific Reports” last month, this study marks a pivotal moment in our understanding of ancient diseases. Brucellosis, the identified ailment, remains prevalent in modern times, with humans typically contracting it through direct contact with infected animals, consumption of contaminated animal products, or inhalation of airborne agents.

The symptoms of brucellosis are diverse, encompassing fever, muscular pain, night sweats, and a range of lasting effects, including arthritis, back pain, testicular inflammation leading to infertility, and endocarditis, which, as Dr. Haeusler notes, is the most common cause of death from the disease. Importantly, this case represents the “earliest secure evidence of this zoonotic disease in hominin evolution,” even predating its discovery in Bronze Age Homo sapiens skeletons dating back approximately 5,000 years.

The transmission of brucellosis to the Neanderthal man is believed to have occurred during the handling and preparation of animals hunted for food. Possible sources include wild sheep, goats, wild cattle, bison, reindeer, hares, and marmots, all of which constituted the Neanderthal diet. Interestingly, mammoths and woolly rhinoceros, two of the larger animals hunted by Neanderthals, are considered unlikely disease reservoirs, at least based on the health of their extant relatives.

Considering that the Neanderthal lived to an advanced age for the period, Dr. Haeusler speculates that he may have suffered from a milder form of the disease. This discovery underscores the significance of the Old Man of Chapelle, who played a pivotal role in dispelling misconceptions about Neanderthals being primitive Stone Age brutes. More recent research indicates that these ancient hominins possessed intelligence on par with our own.

Early interpretations of the skeleton depicted a man with a slouched posture, bent knees, and a forward-jutting head. Subsequent research revealed a different story. Even with the burden of degenerative osteoarthritis, the Old Man of Chapelle would have walked upright. The skeletal remains also suggest that he had lost most of his teeth and likely relied on assistance from other members of his group for sustenance.

In summary, the Neanderthal “Old Man of Chapelle” is teaching us not only about the ancient past but also about the enduring relevance of zoonotic diseases.