In a quest to unravel one of the great enigmas of human evolution—why Homo sapiens is the sole surviving human species—Tom Higham and Katerina Douka, a formidable research duo from the University of Vienna, are employing cutting-edge scientific techniques.

Renowned for their extensive experience, this couple previously worked at the University of Oxford and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, later joining the University of Vienna in 2021. Their research findings are regularly published in high-impact journals, with their latest work featured in Science Advances.

It has long been known that remnants of our ancient relatives are interwoven within modern human DNA. Humans possess a fraction of genes inherited from archaic groups such as Neanderthals, and nearly every individual of European or Asian descent carries an average of two percent Neanderthal DNA in their genetic makeup, with a slightly lower proportion for those of African heritage.

This genetic legacy not only underpins certain dispositions observed in contemporary humans but also serves as tangible evidence that different human species engaged in interbreeding over 40,000 years ago.

Tom Higham and Katerina Douka, molecular archaeologists by trade, are accustomed to scrutinizing fragments of ancient bones and teeth, employing a diverse array of archaeological research methods, from traditional tools to state-of-the-art equipment such as laser-based mass spectrometers. For over a decade and a half, they’ve collaboratively worked with other experts to deepen our comprehension of the pivotal Paleolithic era, also known as the Old Stone Age.

It’s now evident that during this period, spanning 150,000 to 30,000 years ago, our planet was home to a minimum of eight distinct human species—potentially even more—fostering genetic exchange among them.

Today, Tom Higham remarks on this unique period in human evolution, stating, “Today is a very unusual time in terms of human evolution.” He goes on to highlight the remarkable fact that for several million years, humanity coexisted with various hominin groups before being left as the sole surviving human species, along with our great ape relatives.

One of the key discoveries in their extensive research emerged from a minuscule bone fragment extracted from Siberia’s Denisova Cave—a finding that Katerina Douka regards as profoundly significant for the study of early human history. This discovery eventually settled debates among researchers regarding whether different human species had interacted and exchanged genetic material.

The turning point arrived in 2010 when the Neanderthal genome was unveiled, confirming that modern humans had indeed interbred with Neanderthals. However, the extent of these interbreeding events was greater than initially assumed.

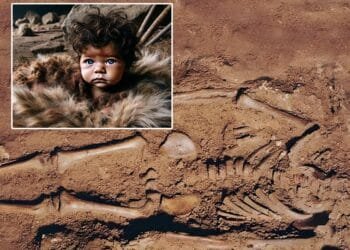

In 2015, the research duo employed a groundbreaking collagen fingerprinting technique called ZooMS and identified a small bone fragment with ancient mitochondrial DNA that was initially attributed to Neanderthals. Yet, further sequencing revealed that the bone belonged to a 13-year-old girl whose mother was Neanderthal, while her father was Denisovan—a truly groundbreaking find, marking the first-generation offspring of two distinct human types.

Tom Higham underscores the remarkable progress in the field, remarking, “Before 2010, such analyses were not possible because the methods did not exist then. We can now take a few milligrams of powder from tiny archaeological bone fragments—there are bags of bones, tons of them, sitting in storage facilities—and identify the bones to species, thereby finding potential human bone fragments hiding, like this little Denisovan bone.”

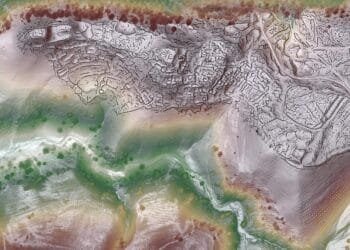

A couple and a dream team when it comes to investigating ancient DNA and unravelling secrets of early human history: Katerina Douka and Tom Higham. The two archaeologists are not only research colleagues – they are also a couple. At the moment, they are still in the process of setting up their offices and laboratories. Some pictures in the background are still waiting to be hung up. Credit: feelimage – MaternWhile the study of human origins requires a myriad of scientific methods, Tom Higham emphasizes that contemporary archaeological science relies on an arsenal of techniques from different fields, including artificial intelligence, laser-based satellite technology for 3D surface reconstruction, electron microscopes, CT scanners, and particle accelerators. This multi-disciplinary approach has led to a surge in the methods available for answering critical archaeological questions in the last two decades.

The significance of archaeological science extends far beyond delving into the past; it is the sole means to comprehend our ancient history, predating the advent of writing and record-keeping. Tom Higham notes the astonishing closeness of human relations, evident through instances of interbreeding among different human groups.

As for the future, Tom Higham and Katerina Douka aim to explore the coexistence of diverse human species 50,000 years ago and unravel the fate of our extinct relatives. The question of whether Neanderthals simply disappeared or interbred with Homo sapiens has been partially answered, revealing that their DNA lives on within us. Still, it has raised new questions that drive their research forward.

Their work holds the potential to position Vienna as a global center for this type of research, given the substantial number of experts currently engaged in the field. On their desks, a substantial collection of bone samples awaits probing, representing the next frontier in addressing the profound mysteries of human origins, which may be concealed within the next minuscule bone awaiting examination.

More information:

Ludovic Slimak et al, (2022), Modern human incursion into Neanderthal territories 54,000 years ago at Mandrin, France, Science Advances. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abj9496

Viviane Slon et al, (2018), The genome of the offspring of a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father, Nature. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-018-0455-x