Daniel Wilson, a distinguished 19th century Canadian archaeologist, first came to Newark in 1856. He wanted to see for himself the amazing earthworks described in the first publication of the Smithsonian Institution — “Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley.”

The authors, Ephraim Squier and Edwin Davis, devoted seven pages of their book to Newark, but frankly admitted that these earthworks “are so complicated, that it is impossible to give anything like a comprehensible description of them.”

So Wilson came to Newark to see what he could make of them.

He later wrote the following about that first visit: “… after driving over a circuit of several miles, embracing the remarkable earthworks … all idea of mere combined labor is lost in the higher conviction of manifest skill and even science.”

Wilson was unaware of the deep knowledge of geometry and astronomy that we now know was encoded in the earthworks, but he recognized the science behind the scale, symmetry, and precision of their design and construction.

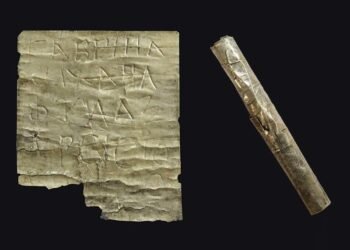

He compared the Newark Earthworks to “the British Avebury” and “the temples and sphinx-avenues of the Egyptian Karnak and Luxor,” but by no means was he suggesting any direct connections between these wonders of the world. He was familiar with the Newark Holy Stones “and other similar productions of perverted American ingenuity,” which were used then, and still are being used, as supposed proof that various Old World civilizations and not Indigenous American Indians actually built the monumental earthworks.

Wilson dismissed the Holy Stones and the other frauds as “the work of such illiterate and shallow knaves, that they scarcely merit notice, were it not for the amount of discussion they excited, before the all engrossing civil war preoccupied the public mind with its stern realities.”

My colleagues, local historian Jeff Gill, Jenn Bush, Director of the Johnson-Humrickhouse Museum, and I agree with Wilson that the Newark Holy Stones are 19th century fakes, but we do not agree that they are the work of illiterate and shallow knaves. Instead, we’ve argued that they were scientific forgeries crafted by educated and well-intentioned men to undermine the racist theory of polygenesis, which argued that American Indians and Sub-Saharan Africans were subhumans and therefore not entitled to basic human rights.

Wilson also was opposed to this notion, at least insofar as it related to American Indians. He wrote that while it was “natural and reasonable that the men of the sixteenth century should believe” that America was peopled with “monstrosities” rather than with “human beings like ourselves”; but it was incredible “to see men of science still finding it difficult to emancipate themselves from the idea.”

Gill, Bush and I also agree that concerns over an impending American Civil War gave the Holy Stones forgeries a special urgency; and that the outcome of that war, the end of slavery, made them more or less irrelevant and so they largely slipped from the public mind.

Wilson made several visits to Newark over the years and even became a corresponding member of the Licking County Pioneer, Historical and Antiquarian Society. He was fascinated by the Newark Earthworks with their “perplexing element of elaborate geometrical figures, executed on a gigantic scale by a people” who had no metal tools, “and yet giving proof of skill fully equaling, in the execution of their geometrical designs, that of the scientific land-surveyor.”

This perplexing element is one facet of our argument that the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks have the Outstanding Universal Value required for inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List alongside sites such as Avebury, Karnak and Luxor.

By Brad Lepper, the Senior Archaeologist for the Ohio History Connection’s World Heritage Program.

By Brad Lepper, the Senior Archaeologist for the Ohio History Connection’s World Heritage Program.