Tutankhamun, also known as King Tut, held the throne of ancient Egypt for approximately a decade, making him one of the most renowned pharaohs in history. His fame largely stems from the remarkably preserved condition of his tomb, where his image and associated artifacts have been extensively showcased.

While the tomb of Tutankhamun likely fell victim to looters and treasure seekers in antiquity, remarkably, his mummy and the majority of his burial items managed to endure through the ages. The tomb’s strategic location, nestled within the valley floor and concealed by the accumulation of debris resulting from natural floods and tomb construction, helped safeguard its entrance from discovery.

King Tut: Who Was He?

Tutankhamun, who reigned around 1341 BC to 1323 BCE, held the position of an Egyptian pharaoh during the concluding years of the 18th Dynasty within the New Kingdom era of Egyptian history.

His ascension to the throne took place around 1334 BCE, when he was just nine years old, following the demise of his father, Akhenaten, and the brief reigns of Neferneferuaten and Smenkhkare.

Tutankhamun’s accession to power occurred during a period of significant religious upheaval orchestrated by Akhenaten, who had introduced the worship of a single deity, Aten, while disregarding other gods.

This transformation ushered in what is now known as the Amarna Period. One of Tutankhamun’s notable achievements was the restoration of traditional religious practices, a pivotal act during his reign.

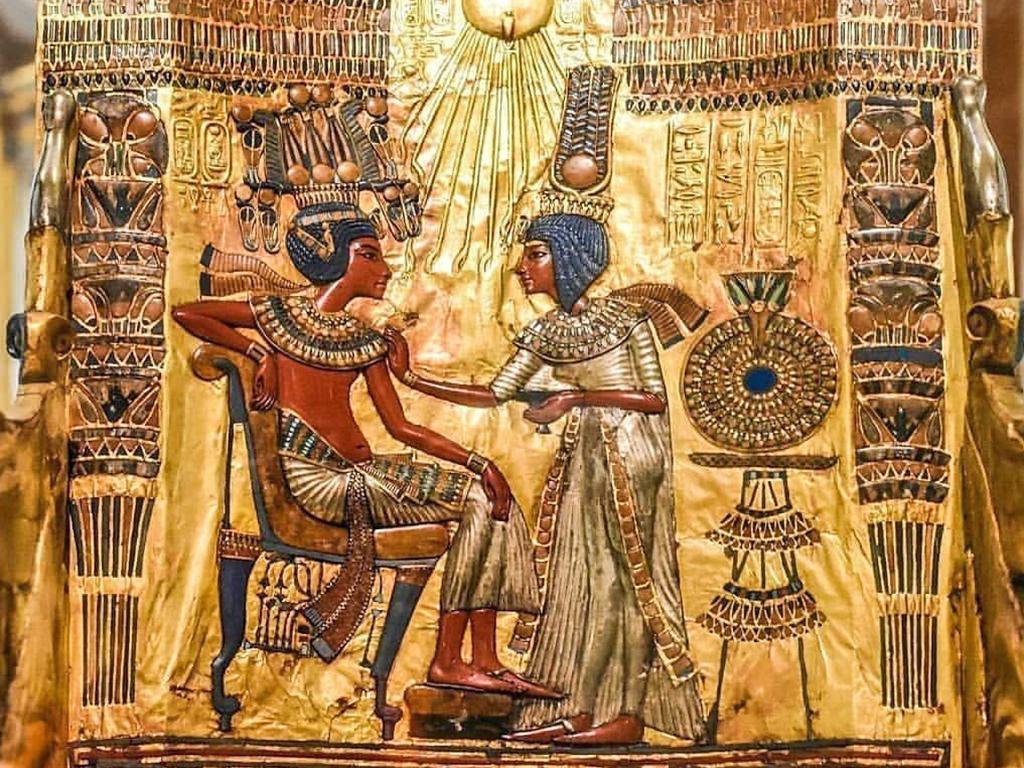

To signify this shift, his name was altered from Tutankhaten, which bore reference to Akhenaten’s deity, to Tutankhamun, which honored Amun, a crucial figure in the traditional Egyptian pantheon. A parallel change was made to the name of his queen, from Ankhesenpaaten to Ankhesenamun.

Tutankhamun married his half-sister Ankhesenamun, yet the couple did not produce any offspring. Tragically, his life was cut short at the tender age of eighteen, and to this day, the cause of his untimely demise remains shrouded in mystery, with theories ranging from a chariot accident to a fatal blow to the head or even a fatal encounter with a hippopotamus.

Where is the tomb of King Tut?

King Tut’s tomb, designated KV62, is situated in the eastern branch of the Valley of the Kings, positioned between the tombs of Rameses II and Rameses IV.

Who discovered the tomb?

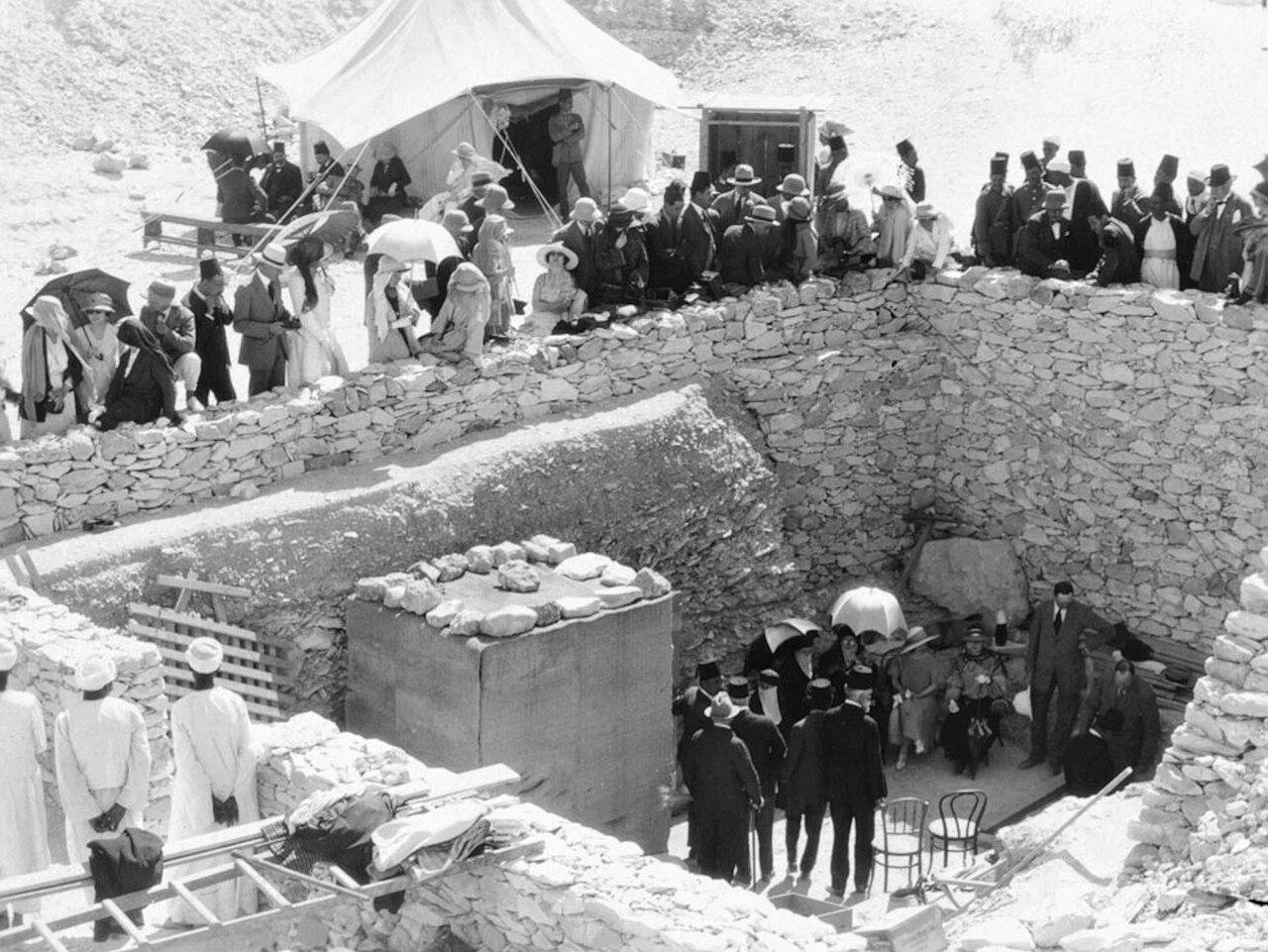

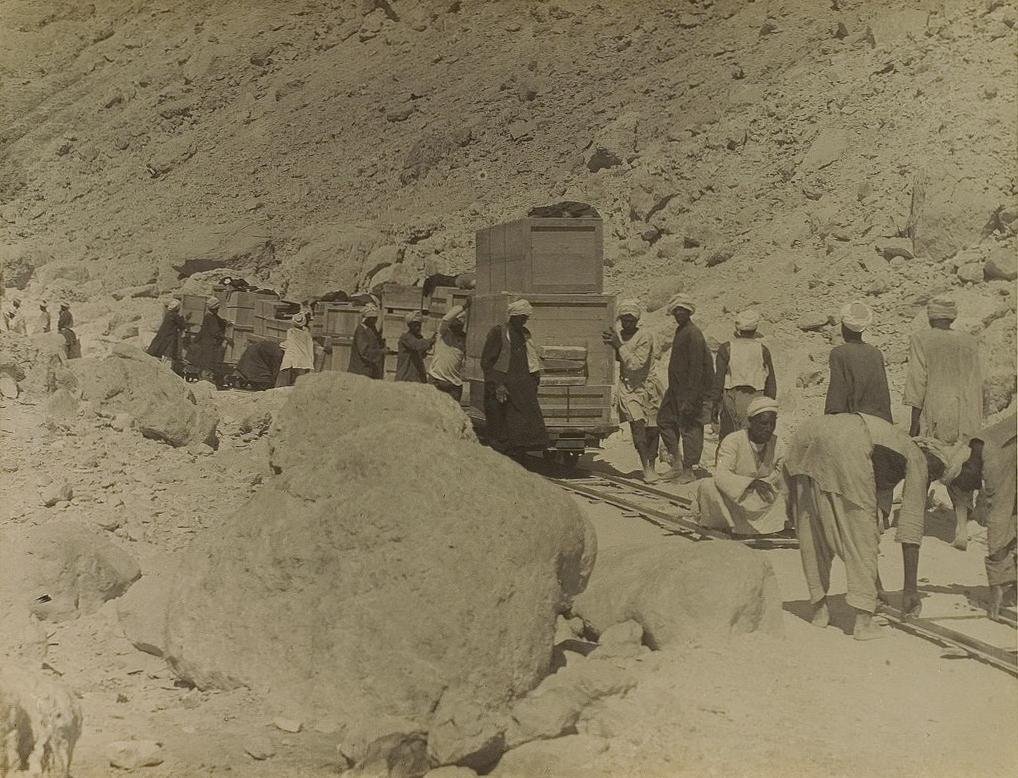

The momentous discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb was attributed to a team of excavators led by the English archaeologist Howard Carter in the year 1922.

By 1914, many archaeologists believed that they had unearthed all the tombs of the Pharaohs within the Valley of the Kings. However, Howard Carter remained steadfast in his conviction that the tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun was still concealed within the valley.

Carter dedicated five years to scouring the Valley of the Kings, initially encountering disappointment. His patron, Lord Carnarvon, grew impatient and nearly terminated funding for the quest. Nonetheless, Carter managed to persuade Carnarvon to extend his financial support for an additional year.

In 1922, after six years of relentless searching, Howard Carter stumbled upon a crucial clue—an underground step hidden beneath aged workmen’s huts. Swiftly, he revealed a stairway leading to the entrance of King Tut’s tomb.

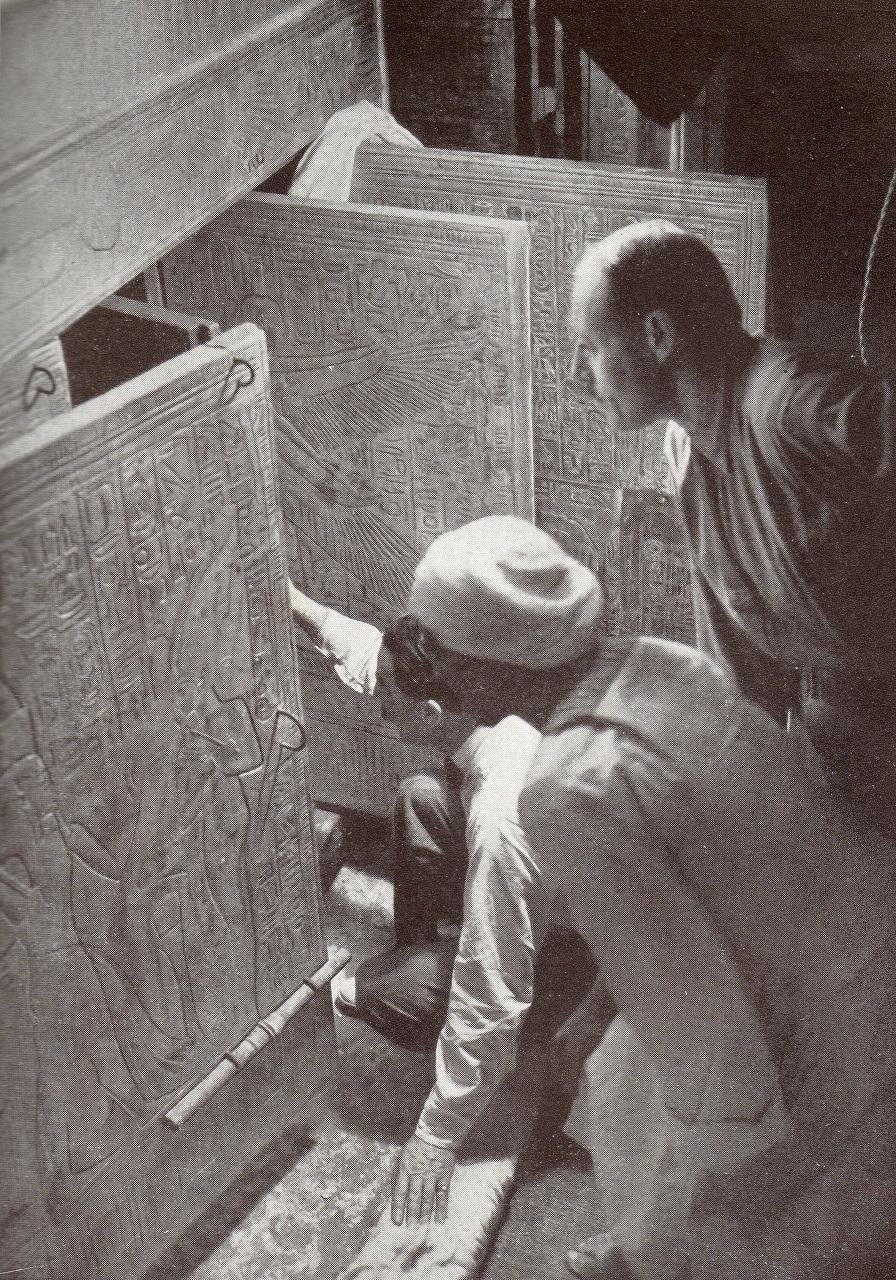

On November 26 of that year, when Carter and Lord Carnarvon ventured into the tomb’s inner chambers, they were overcome with exhilaration. What they encountered was nothing short of astounding: the tomb, after more than three millennia, remained virtually intact, with its treasures untouched. The explorers embarked on their meticulous investigation of the tomb’s four chambers, marking the beginning of a historic journey into the legacy of King Tutankhamun.

Tutankhamun’s Tomb: Architecture

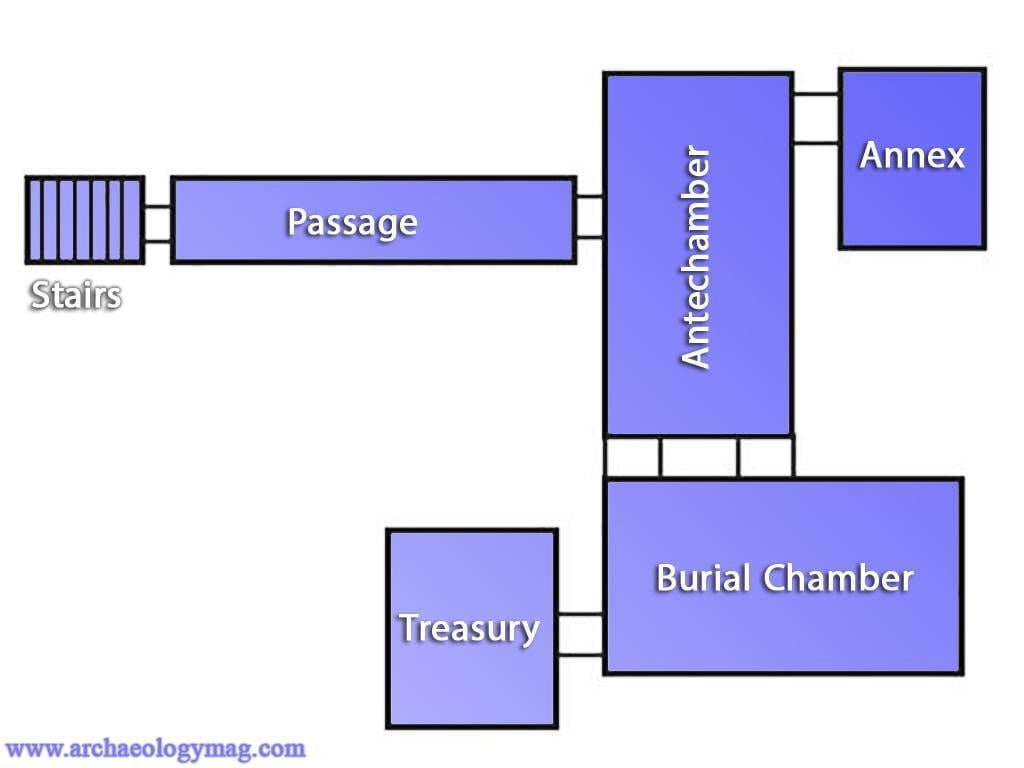

Tutankhamun’s tomb was meticulously crafted in the fashion of the kings from the illustrious eighteenth dynasty. This regal resting place comprises four chambers, including an entry staircase and a connecting corridor. The tomb layout entails an east–west descending corridor, an antechamber positioned at the western terminus of the passage, an annex, a burial chamber, and a room adjacent to the burial chamber, famously known as the treasury. It is possible that the burial chamber and treasury were later additions to the original tomb, tailored specifically for Tutankhamun’s interment.

Originally, doorways between the stairway and the corridor, the corridor and the antechamber, the antechamber and the annex, and the antechamber and the burial chamber were sealed with partitions fashioned from limestone and plaster. These partitions bore intricate impressions from seals held by various officials involved in Tutankhamun’s burial and restoration efforts. These seals featured hieroglyphic inscriptions that celebrated Tutankhamun’s devotion to the gods throughout his reign. Regrettably, these partitions were breached by robbers, and while most of the breaches were subsequently repaired by restorers, the hole created by the robbers in the annex entryway remained unsealed.

Upon entering the tomb, a flight of stairs leads to a short corridor. Initially, this stairway consisted of sixteen steps, but the bottom six steps were intentionally removed during the burial process to accommodate the passage of the largest funerary items through the doorway. Later, these steps were reconstructed, only to be removed again by excavators when the same monumental items were extracted from the tomb.

The first room encountered within the tomb is the antechamber, where numerous furnishings destined for Tutankhamun’s eternal journey were unearthed. An annex is linked to this chamber, and at its far end, there is an entrance leading to the burial chamber.

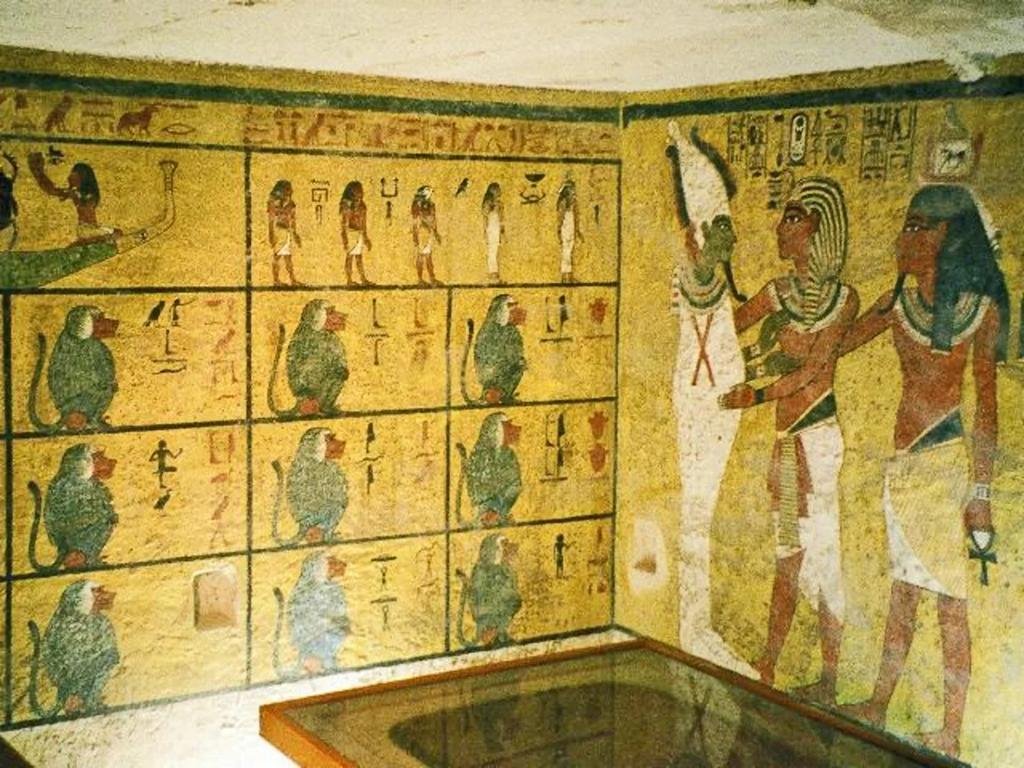

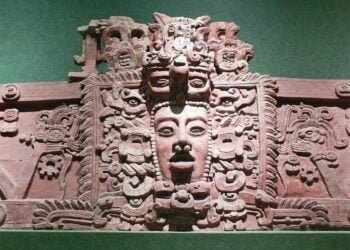

Within the burial chamber, four niches adorn the walls, each housing “magic bricks” inscribed with protective spells. Apart from the impressions of seals, the sole adornment in the tomb is found in the burial chamber, where figures set against a yellow backdrop grace the walls.

The chamber heights vary from 2.3 to 3.6 meters, with the annexe, burial chamber, and treasury floors positioned about 0.9 meters below the antechamber’s floor. Notably, a small niche on the west wall of the antechamber once served as a maneuvering point for transporting the sarcophagus through the room.

Guarding this chamber were two obsidian-black sentry statues symbolizing the royal ka (soul) and the aspirations for rebirth, qualities associated with Osiris, the deity who achieved rebirth after death.

In contrast to other contemporary royal tombs in Egypt, Tutankhamun’s final resting place is somewhat smaller and exhibits less intricate ornamentation, possibly due to its adaptation for Tutankhamun following his untimely demise.

Remarkably, the east wall of the tomb features an image portraying Tutankhamun’s funeral procession, a motif distinctively absent in other royal tombs. The north wall showcases Ay conducting the sacred Opening of the Mouth ritual upon Tutankhamun’s mummy, a ritual that validated him as the rightful heir to the throne. Tutankhamun is also depicted on this wall, receiving the blessings of the goddess Nut and the god Osiris for the afterlife.

The south wall portrays the king in the company of the deities Hathor, Anubis, and Isis. This wall bore a unique challenge, as part of its decoration was painted on the partition that separated the burial chamber from the antechamber, necessitating the destruction of the figure of Isis during the removal of the partition during tomb clearance.

The west wall features a striking depiction of twelve baboons, extracted from the first segment of the Amduat, a funerary text recounting the sun god Ra’s journey through the netherworld.

Intriguingly, the figures on three of the walls exhibit the distinctive proportions characteristic of Amarna Period art, while the south wall reverts to the conventional proportions observed in art preceding and following the Amarna era.

What did archaeologists find inside the tomb?

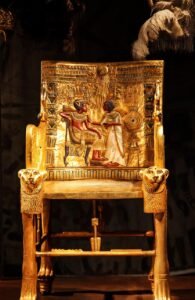

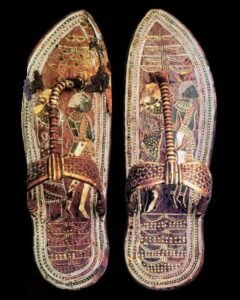

Tutankhamun, like other pharaohs, was buried with a vast array of funerary possessions and personal treasures, necessitating a meticulous arrangement due to the spatial constraints of the tomb.

Among these cherished items were statues, resplendent gold jewelry, Tutankhamun’s mummy, intricately designed chariots, meticulously crafted model boats, the revered canopic jars, elegant chairs, and captivating paintings.

In the inner sanctum of the burial chamber lay the sarcophagus, cradling the remains of King Tut. This sacred chamber sheltered three intricately nested coffins that enshrined the mummy, culminating in the grandeur of a final coffin wrought entirely from the precious metal, gold.

Unfortunately, Tutankhamun’s mummy was discovered in a state of disrepair, with much of the wrappings and even substantial portions of the mummy’s tissues having undergone carbonization.

Within this hallowed space, Howard Carter also unveiled the resplendent funerary mask of Tutankhamun, an iconic artifact now residing in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, symbolizing the grandeur of ancient Egypt. This exquisite mask stands at a height of 54 cm, spans 39.3 cm in width, and extends to a depth of 49 cm. Fashioned from two layers of high-karat gold, ranging in thickness from 1.5 to 3 mm, this masterpiece weighs an impressive 10.23 kilograms. Adorning the mask’s shoulders is an ancient spell from the Book of the Dead, meticulously inscribed in hieroglyphs.

The countenance of the pharaoh is poignantly portrayed, bedecked with the regal nemes headcloth adorned with the symbolic emblems of a serpent (Wadjet) and vulture (Nekhbet), emblematic of Tutankhamun’s dominion over both Upper and Lower Egypt.

The mask further boasts an intricate inlay of gemstones, including lapis lazuli (encompassing the eyes and brows), quartz (fashioning the eyes), obsidian (adorning the pupils), along with carnelian, amazonite, turquoise, and faience.

Within this chamber, two mummified fetuses also found their eternal resting place, representing distinct stages of development—one at five months and the other ranging between seven to nine months. Intriguingly, the coffins enclosing these fetal remains remain unmarked with their names—referred to as 317a(2) for the smaller fetus and 317b(2) for the larger one. Remarkably, both Tutankhamun’s mummy and these fetal specimens have undergone genetic analysis.

In a pivotal discovery, DNA analysis conducted in 2010 on the mummies within the Valley of the Kings unveiled the familial connection, establishing these fetuses as Tutankhamun’s offspring. Their mother, identified from her mummy discovered in KV21, is presumed to be Ankhesenamun.

The tomb held an astonishing treasure trove of nearly 5,000 artifacts in total. Over the span of a decade, Howard Carter and his dedicated colleagues meticulously cataloged every item, preserving for eternity the captivating legacy of Tutankhamun.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.