Archaeologists discovered 10,500-year-old cremated bones in a Stone Age campsite in northern Germany. Not only are these the earliest human remains discovered at the site, but they are also the oldest known burial in northern Germany.

The finding represents the first time human remains have been discovered at Duvensee bog in the Schleswig-Holstein region, and it is the earliest known burial site in northern Germany. The campsite is one of at least 20 Mesolithic and Neolithic campsites at Duvensee, and it is located on what was once the prehistoric lake’s western shore.

The remains are one of the only ones discovered in Europe from the early Mesolithic period. According to Live Science, archaeologists believe that ancient people buried their dead close to where they died, and that specialized graveyards were not used until later ages.

Hazelnuts were a big attraction in the area because Mesolithic people could gather and roast them, Harald Lübke(opens in new tab), an archaeologist at the Center for Baltic and Scandinavian Archaeology, an agency of the Schleswig-Holstein State Museums Foundation, told Live Science.

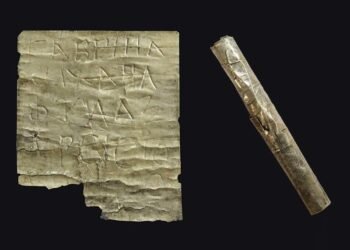

Archaeologists discovered flint tools at the bog site as well. Because flint does not exist naturally in the area, Lübke told Live Science that ancient communities likely repaired their flint tools and weapons there after migrating to the bog for the fall hazelnut harvest.

The burial was discovered earlier this month during excavations at a site first identified in the late 1980s by archaeologist Klaus Bokelmann and his students, who found worked flints there not during a formal excavation, but during a barbecue at a house on the edge of a nearby village, Lübke said.

“Because the sausages were not ready, Bokelmann told his students that if they found anything [in the bog nearby], then he would give them a bottle of Champagne,” he said. “And when they came back, they had a lot of flint artifacts.”

The first sites investigated by Bokelmann in the 1980s were on islands along the lake’s western shore, which has fully silted up over the last 8,000 years or so, forming a peat bog known as a “moor” in Germany.

Archaeologists have recovered bark mats for sitting on damp soil, pieces of worked flint, and the remains of many Mesolithic fireplaces for roasting hazelnuts, but no burials have been identified at the island sites.

“Maybe they didn’t bury people on the islands but only at the sites on the lake border, which seem to have had a different kind of function,” Lübke added.

The finding of human remains at the site sheds light on another aspect of life for the bog’s hunter-gatherers, but many questions remain.