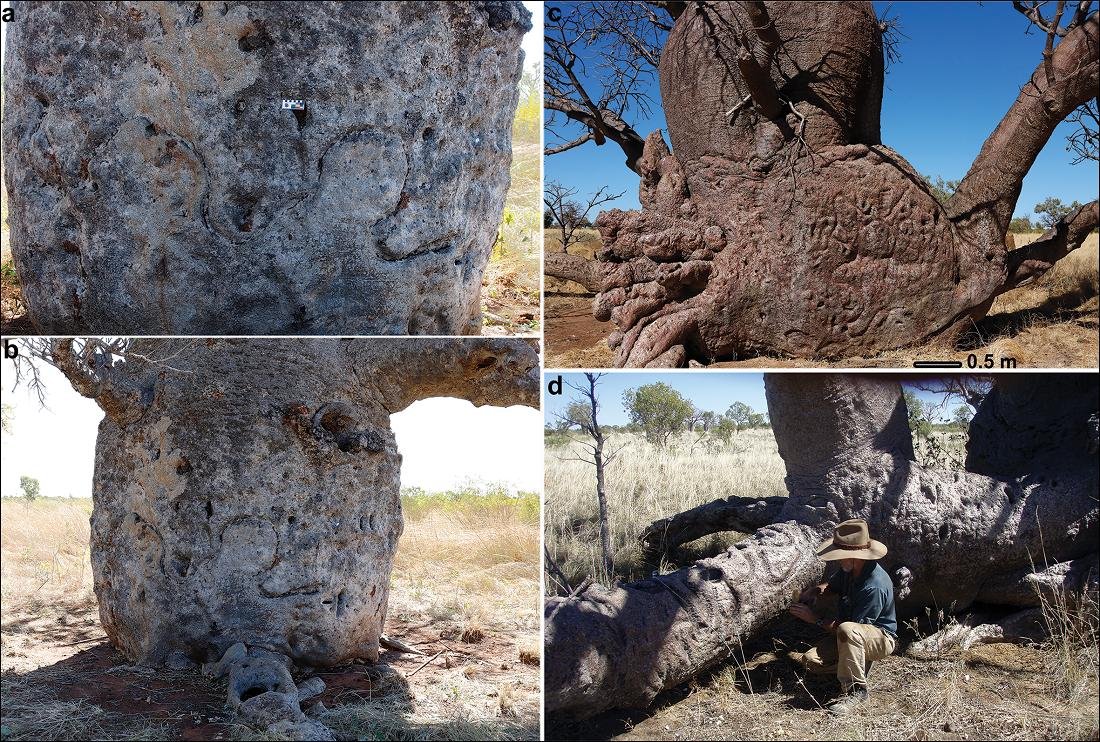

A collaborative effort between researchers and a group of First Nations Australians is underway to document ancient art found in the bark of Australia’s boab trees. In the remote Tanami Desert, a survey is being conducted to locate and record these trees.

Carved trees, also referred to as dendroglyphs or arborglyphs, represent a captivating yet largely undiscovered form of cultural heritage in Australia. Despite being overshadowed by the magnificent rock art found across the continent, these trees serve as a significant expression of Aboriginal visual cultural practice and tradition.

The broader category of culturally modified trees, encompassing various forms of scarring from resource extraction and cultural activities, is emerging as a growing area of study.

The Australian boab (Adansonia gregorii), easily identified by its large, bottle-shaped trunk, holds economic importance for Indigenous Australians, as its pith, seeds, and young roots are consumed.

Additionally, many of these trees bear cultural significance, featuring motifs and symbols carved into their bark. After over two years of fieldwork involving researchers from The Australian National University (ANU), The University of Western Australia, and The University of Canberra, 12 trees with carvings were discovered through collaboration with five Traditional Owners.

Professor Sue O’Connor, from the ANU School of Culture, History, and Language, notes that many of the carved trees are centuries old, underscoring the urgency to create high-quality recordings before these heritage trees succumb.

Boabs, unlike most Australian trees, have soft and fibrous inner wood, leading them to collapse upon death. This remarkable artwork, comparable in significance to the renowned rock art, is now at risk of being lost.

Brenda Gladstone, a traditional owner, emphasizes the importance of preserving Indigenous knowledge and stories for future generations, describing the effort as a race against time.

Professor O’Connor added Australian boabs have never been successfully dated. “They are often said to live for up to 2,000 years but this is based on the ages obtained from some of the massive baobab trees in South Africa which are a different species,” she says. “We simply don’t know how old the Australian boabs are.

Although more boabs are visible on Google Earth, researchers couldn’t explore them during this trip. However, they remain targets for examination on future Tanami adventures.

Researchers posit that, similar to the retouching of rock art to perpetuate creation stories, carvings on boab trees were regularly re-grooved. This practice likely served to maintain knowledge of the Dreamtime creative process and ensure that people’s obligations to observe the law stayed fresh in the memory of those using such campsites.

The collaboration in this project illustrates how incorporating traditional Indigenous knowledge into archaeological inquiries enriches our understanding of the cultural landscape and contributes to our knowledge of dendroglyphs in Australia.

More information: O’Connor, S., Balme, J., Frederick, U., Garstone, B., Bedford, R., Bedford, J., . . . Lewis, D. (2022). Art in the bark: Indigenous carved boab trees (Adansonia gregorii) in north-west Australia. Antiquity, 1-18. doi:10.15184/aqy.2022.129