The current excavations in Uppåkra are at the forefront of cutting-edge archaeological techniques. Researchers are currently solving significant parts of a historical puzzle by combining big data, data modeling, and DNA sequencing. Perhaps we’ll find out if the Justinianic Plague, the forerunner of the Black Death, reached Uppåkra. This has been uncertain until now.

Torbjörn Ahlström, Lund University’s professor of Historical Osteology, stands on a hill outside Lun. His gaze falls on the fertile soil that has served people in the area for centuries.

Torbjörn Ahlström is about to start a new project in Uppåkra. It is now a quiet village in southern Sweden’s countryside, but it was once the most powerful center in the Nordic countries for nearly 1,000 years (between 100 BCE and the 10th century).

Uppåkra is the largest Iron Age settlement in the Nordic countries and one of Northern Europe’s richest archaeological sites. So far, excavation has been periodic and has covered only a fraction of the area.

“However, the autumn of 2022 is special. We will now reveal Hallen, a 30-meter-long building at the heart of the community, the very epicenter of power in Uppåkra”, says Torbjörn Ahlström.

Supported by new techniques

The archeological team working on Hallen is an experienced group that includes “ordinary” archaeologists, an archaeologist in charge of stratigraphy (documenting the different cultural layers), an animal osteologist (analyzing animal bones), and a palaeobotanist (studying fossilized plants).

“Archaeology is in the midst of its third science revolution, providing us with entirely new opportunities”, Torbjörn Ahlström adds.

Simply put, the team is combining several different techniques to paint a broad picture of life in the Nordic countries’ great power center.

“For example, we use DNA sequencing in combination with isotope analyses of strontium, oxygen, carbon and nitrogen. This has, in fact, revolutionized archaeology and gives us answers about kinship, mobility, habits and health in ancient cultures” Sandra Fritz, Historical Osteology Project Assistant at Lund University, explains.

Different findings can be detected and matched against global databases by sequencing prehistoric DNA.

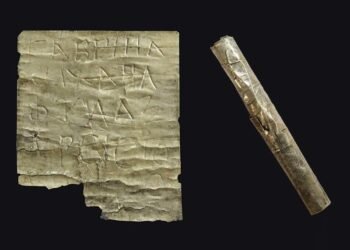

“We extract soil DNA from cultivated soil, a method that is completely new, which basically means we take a soil sample and extract all the available DNA”, says Torbjörn Ahlström.

A tube is pushed into the earth and sent to a laboratory for DNA analysis. This technique differs from other forms of DNA analysis that use bone fragments from animals or humans rather than soil.

“Combined with other methods such as micromorphology, archaeogenetics and isotopes and radiographic analyses, it gives us a good chance of getting a fairly detailed picture of the prehistoric conditions in Uppåkra”, says Sandra Fritz.

“Personally, I hope to find the answer to whether Uppåkra was reached by the Justinianic Plague, the forerunner of the Black Death, which swept through here in several waves between 1300 and 1700. We know that Germany and England suffered from the Justinianic Plague in the 6th century, but it has not yet been pinpointed in Scandinavia”, explains Torbjörn Ahlström.

Uppåkra found by accident

Uppkra was more or less discovered by accident. In 1934, the foundations of a pigsty were to be dug near the church in the village of Uppåkra,

“The soil revealed the first signs of the community in Uppåkra. Today we have 28,000 artifacts; pottery, charred bones and charcoal – in short, a massive prehistoric site”, says Torbjörn Ahlström.

The entire Uppåkra site is large, covering 50 hectares, and the excavations take time. So far, researchers have discovered a brewery, jewelry, and a glass bowl that was most likely made on the Black Sea’s shores in Uppåkra.

“What was the relationship with the continental Roman Empire? Did the people of Uppåkra fight for it as auxiliary troops? ” says Torbjörn Ahlström.

He points out across the valley and walks along the indicated location of the hall. Four wooden stakes are driven into the ground to mark another central location, Kulthuset.

“This is where religious rituals took place, close to the power center Hallen”, says Torbjörn Ahlström.

Detailing how Hallen went through at least seven different construction phases, he concludes that the placement of Hallen and Kulthuset was important to people – they were always rebuilt on the same spot.

“We hope to uncover a lot of finds that can tell us something about the use of power at this time. The history of what actually happened in Uppåkra’s Hallen is an indication of what happened throughout a large part of the Iron Age”, says Torbjörn Ahlström. — Provided by Lund University