In their search for silver ore, the Romans established two military camps in the Bad Ems area near Koblenz in the 1st century AD. This is the result of research carried out as part of a teaching excavation that spanned several years and was carried out by Goethe University’s Department of Archaeology and History of the Roman Provinces in cooperation with the federal state of Rhineland-Palatinate.

Several surprising findings were made during the process. For one, the exciting research story earned young archaeologist Frederic Auth first place at the Wiesbaden Science Slam.

When Prof. Markus Scholz, who teaches archaeology and the history of Roman provinces at Goethe University, returned to Bad Ems toward the end of the excavation work, he was astonished: After all, all the photos sent by his colleague Frederic Auth showed but a few pieces of wood. Not surprisingly, Scholz was ill-prepared for what he saw next: a wooden defense construction consisting of sharpened wooden stakes, designed to prevent the enemy’s approach.

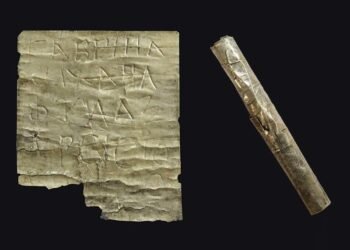

The martial-looking structure was intended to deter enemies from attacking the camp. Such installations — comparable, if you will, to modern barbed wire — are referenced to in literature from the time. Caesar, for instance, mentioned them. But to date, none had been found.

The damp soil of the Blöskopf area obviously provided the ideal conditions: The wooden spikes, which probably extended throughout the entire downward tapering ditch around the camp, were found to be well preserved.

Two previously undiscovered Roman military camps

The work of the Frankfurt archaeologists and Dr. Peter Henrich of the General Directorate for Cultural Heritage of the German federal state of Rhineland-Palatinate, uncovered two previously unknown military camps in the vicinity of Bad Ems, situated on both sides of the Emsbach valley.

The excavations were triggered by observations made by a hunter in 2016, who, from his raised hide, spotted color differences in the grain field, indicating the existence of sub-surface structures. A drone photo of the elevation, which bears the beautiful name “Ehrlich” (the German word for “honest”), confirmed the thesis: the field was crisscrossed by a track that could have originated from a huge tractor.

In reality, however, it was a double ditch that framed a Roman camp. Geomagnetic prospecting later revealed an eight-hectare military camp with about 40 wooden towers.

The archaeological excavations, carried out in two campaigns under the local direction of Dr. Daniel Burger-Völlmecke, revealed further details: the camp, apparently once intended as a solid build, was never completed. Only one permanent building, consisting of a warehouse and storeroom, was located there. The 3,000 soldiers estimated to have been stationed here probably had to sleep in tents. Burn marks show that the camp was burned down after a few years. But why?

It was the student team, led by Frederic Auth, that identified the second, much smaller camp, located some two kilometers away as the crow flies, on the other side of the Emsbach valley. The “Blöskopf” is no blank slate when it comes to archaeology: Exploratory excavations carried out in 1897 uncovered processed silver ore, raising the assumption that a Roman smelting works was once located there.

The thesis was further supported by the discovery of wall foundations, fire remains and metal slag. For a long time it was assumed that the smelting works were connected to the Limes, built some 800 meters to the east at around 110 AD.

These assumptions, considered valid for decades, have now been disproved: The supposed furnace in fact turned out to be a watchtower of a small military camp holding about 40 men. It was probably deliberately set on fire before the garrison left the camp.

The spectacular wooden defense structure was discovered on literally the penultimate day of the excavations — along with a coin minted in 43 AD, proof that the structure could not have been built in connection with the Limes.

Roman tunnels located above the silver deposit

But why did the Romans fail to complete the large camp, instead choosing to abandon both areas after a few years? What were the facilities used for? Archaeologists have found a possible clue in the writings of historian Tacitus: He describes how, under Roman governor Curtius Rufus, attempts to mine silver ore in the area failed in 47 AD.

The yield had simply been too low. In fact, the team of Frankfurt archaeologists was able to identify a shaft-tunnel system suggesting Roman origins. The tunnel is located a few meters above the Bad Ems passageway, which would have enabled the Romans to mine silver for up to 200 years — that is, if only they had known about it. In the end, the silver was mined in later centuries only.

The Romans’ hope for a lucrative precious metal mining operation also explains the military camp’s presence: They wanted to be able to defend themselves against sudden raids — not an unlikely scenario given the value of the raw material. “To verify this assumption, however, further research is necessary,” says Prof. Scholz.

It would be interesting to know, for example, whether the large camp was also surrounded by obstacles meant to hinder an enemy approach. So far, no wooden spikes have been found there, but traces could perhaps end up being discovered in the much drier soil.

Silver mining reserved for later centuries

The fact that the Romans abruptly abandoned an extensive undertaking is not without precedent. Had they known that centuries later, in modern times, 200 tons of silver would be extracted from the ground near Bad Ems, they might not have given up so quickly.

The soldiers who were ordered to dig the tunnels obviously had not been too enthusiastic about the hard work: Tacitus reports that they wrote to Emperor Claudius in Rome, asking him to award the triumphal insignia to the commanders in advance so they would not have to make their soldiers slave away unnecessarily.

All considered, an exciting research story, which Frederic Auth, who has led the excavations in Bad Ems since 2019, also knows how to recount in an exciting way. His account won first prize in an interdisciplinary field of applicants at the 21st Wiesbaden Science Slam in early February. The young archaeologist is already booked for further appearances: Auth will perform in Heidelberg on March 2, in Bonn on March 7, and in Mannheim on March 19.

The research in Bad Ems was carried out jointly with the Directorate of State Archaeology in the General Directorate for Cultural Heritage of Rhineland-Palatinate, the Institute of Prehistory and Early History at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, and the Berlin University of Applied Sciences. Also involved were the hunter and honorary monument conservator Jürgen Eigenbrod and his colleague Hans-Joachim du Roi, as well as several metal detectorists with the necessary permits from the historical monument authorities.

The project was financed with support from the Gerhard Jacobi Stiftung, the Society for Archaeology on the Middle Rhine and Moselle, and the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG). The wooden spikes have meanwhile been preserved at the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum in Mainz.