Archaeologists from Cotswold Archaeology have recently discovered the remains of a watermill in Buckinghamshire, England, as part of the HS2 Archaeology Program.

Excavations were conducted in collaboration with CA and COPA partners. The Buckinghamshire Archaeological Society conducted a study on the watermill, which operated until the early 19th century.

Evidence suggests that the site’s activity continued into the medieval era. The estate where the mill was discovered was established after 949 to support the establishment of the burh at Buckingham.

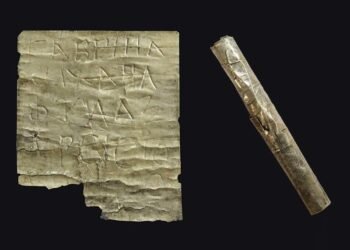

The earliest activity recorded at the site was a possible prehistoric ring ditch. A Mesolithic mace head was recovered from the fill of a post-medieval quarry pit that truncated this ring ditch; the mace head may have originated from a truncated deposit inside the putative ring ditch.

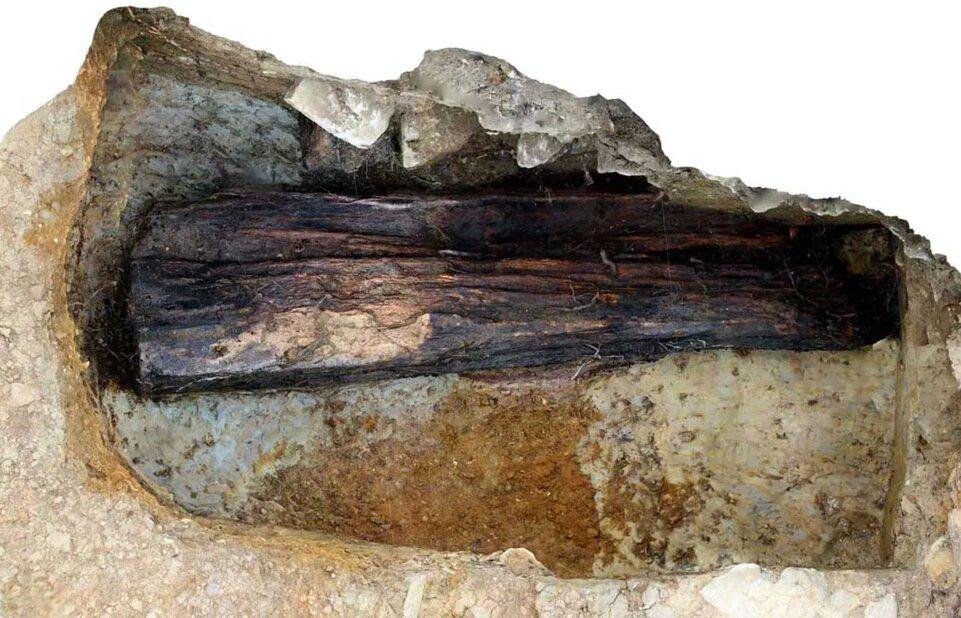

Based on archaeological remains, it appears that the watermill was operational during the 13th century. The remains of three timber beams, which are partially exposed and set in a sizeable clay packing deposit, indicate that they may have formed part of a timber building’s corner.

The positioning of these beams, which are situated directly north of the mill race and outflow pond, leads us to believe that they may have formed the western portion of the watermill’s structure. This structure would have facilitated the connection of the watermill’s drive mechanism to the waterwheel.

The mill structures’ final phase was built during the late post-medieval period and is still present on the site. The walls of the mill race were robustly constructed to channel water to the mill wheel, presumably located beneath the existing farm track that was not investigated during the project. The height of the walls and the broad funnel indicate that a significant amount of water could flow through it. However, the surviving mill race has a gentle slope, possibly due to modern ditch management after the mill’s abandonment.

The excavation also uncovered a related building with two predominantly stone-constructed rooms. Within the northern room, a series of postholes formed an internal partition that enclosed a stone rubble surface. In the southern room, a brick floor surface was discovered, which along with the wall material, dates back to the 18th century or later.

No evidence of the Anglo-Saxon watermill recorded in the Domesday Book was identified, and it is improbable that all remnants and characteristics linked to an earlier watermill were obliterated, despite the site’s extensive use from the medieval era onward. This implies that the Anglo-Saxon watermill was sited elsewhere.

The excavation of the watermill site provides valuable insights into the history of watermills in medieval and post-medieval England. By uncovering the remains of the watermill, archaeologists have shed light on an important aspect of England’s history that might have otherwise been lost to time.