New evidence challenges long-held beliefs about the gendered division of labor in hunter-gatherer societies, revealing that women have been actively involved in hunting, fishing, and warfare throughout history. Recent archaeological findings and analysis of ethnographic reports from the past century suggest that women have played a significant role in providing food and contributing to human survival.

A comprehensive review led by Abigail Anderson of Seattle Pacific University examined 63 modern foraging societies from various regions, including the Americas, Africa, Australia, Asia, and the Oceanic region.

The analysis revealed that nearly 80 percent of these societies had evidence of female hunting, and in cases where hunting was the primary source of food, women actively participated in hunting 100 percent of the time.

Contrary to common assumptions, women did not let childcare hinder their hunting activities, as they often brought their children, including infants, along with them.

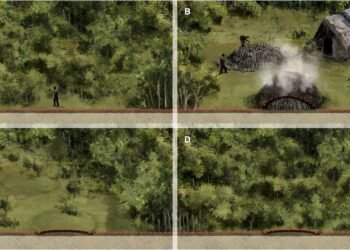

The research challenges the traditional notion of “man the hunter” and “woman the gatherer,” highlighting that women have been involved in hunting for millennia. Female hunters employ unique strategies and toolkits compared to their male counterparts.

For example, Agta women in the Philippines use knives and often hunt in teams during the day, while men primarily use bows and arrows and hunt alone at night.

Moreover, women exhibit specialization in hunting specific prey. In societies like the Tiwi in Australia, women primarily hunt small animals, while men focus on larger game. In the Matses society of the Peruvian Amazon, women specialize in hunting large game using sticks and machetes.

Historically, scientific bias has contributed to the overlooking of female hunters. For instance, archaeologists often assumed that human remains found near weapons belonged to males, leading to an underrepresentation of female warriors. Recent discoveries, however, have challenged these assumptions, demonstrating the presence of female warriors in Viking and Scythian cultures.

The study emphasizes the need to reassess existing paradigms and interpretations of archaeological and ethnographic data, ensuring that biases do not shape scientific understanding. By acknowledging the extensive evidence of women’s involvement in hunting and other “violent” activities, a more accurate representation of female behavior emerges.

Women’s contributions to hunting are not limited to participation alone but also extend to the development of specialized skills. Different cultures exhibit variations in hunting tools and strategies used by women, reflecting distinct training regimes and cultural norms surrounding hunting, meat processing, and consumption.

Women hunters often display greater flexibility in hunting strategies and engage in partnerships with a diverse range of individuals, including husbands, other women, children, and dogs. In contrast, men primarily hunt alone or with a single partner.

The specialization and flexibility exhibited by women hunters challenge the perception that hunting is exclusively a male domain.

Contrary to the belief that childcare hinders women’s hunting activities, research suggests that infants and children frequently accompany adults on hunting expeditions. Various foraging societies have evidence of children being carried during hunts, highlighting the importance of infants remaining with adults. This challenges the notion that women’s caregiving responsibilities prevent their active participation in hunting.

The data compiled from ethnographic reports demonstrate that women in foraging societies across the world have historically engaged in hunting, regardless of their child-bearing status.

These findings disrupt the traditional hunter/gatherer paradigm and emphasize the diversity and flexibility of human subsistence cultures. By recognizing the contributions of women to hunting, a more inclusive framework can be developed to understand human culture.

The study calls for a reevaluation of archaeological evidence, a reassessment of ethnographic data, and a deconstruction of the “man the hunter” narrative. The term “forager” is proposed as a more inclusive alternative that acknowledges the non-sexual division of labor in hunting and gathering.

By embracing this new perspective, future research can better interpret past and future discoveries in the context of female hunters and challenge preconceived notions about gender roles.

The study was published in PLOS ONE.