Researchers led by the Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research, in collaboration with The Sarawak Museum Department, have made a significant discovery by dating the drawings found in Gua Sireh Cave in Sarawak, shedding light on a story of conflict.

This limestone cave in western Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo, is renowned for its charcoal drawings adorning its chambers, attracting numerous visitors. The drawings depict Indigenous resistance to frontier violence in the 1600s and 1800s CE.

Radiocarbon dating of the drawings has revealed their age to be between 280 and 120 cal BP (CE 1670 to 1830), aligning with a period of escalating conflict as Malay elites, who controlled the region, imposed heavy tolls on Indigenous hill tribes, including the Bidayuh. These radiocarbon dates are groundbreaking as they mark the first chronometric age determinations for Malaysian rock art.

The research team, led by Dr. Jillian Huntley, initially sought to confirm that charcoal had been used to create the drawings, as radiocarbon dating relies on carbon-bearing materials. The analyses, conducted in collaboration with Dr. Emilie Dotte-Sarout at the University of Western Australia, confirmed that various species of bamboo charcoal had indeed been used, ensuring the drawings’ suitability for dating. Due to their placement on limestone walls, the drawings have been remarkably well-preserved.

These black drawings are part of a broader distribution of art found from the Philippines through central Island Southeast Asia across Borneo and Sulawesi to Peninsular Malaysia, linked to the Austronesian-speaking peoples’ diaspora.

Previous research by the Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research had dated similar drawings in the Philippines to around 3,500 years ago and in southern Sulawesi to approximately 1,500 years ago.

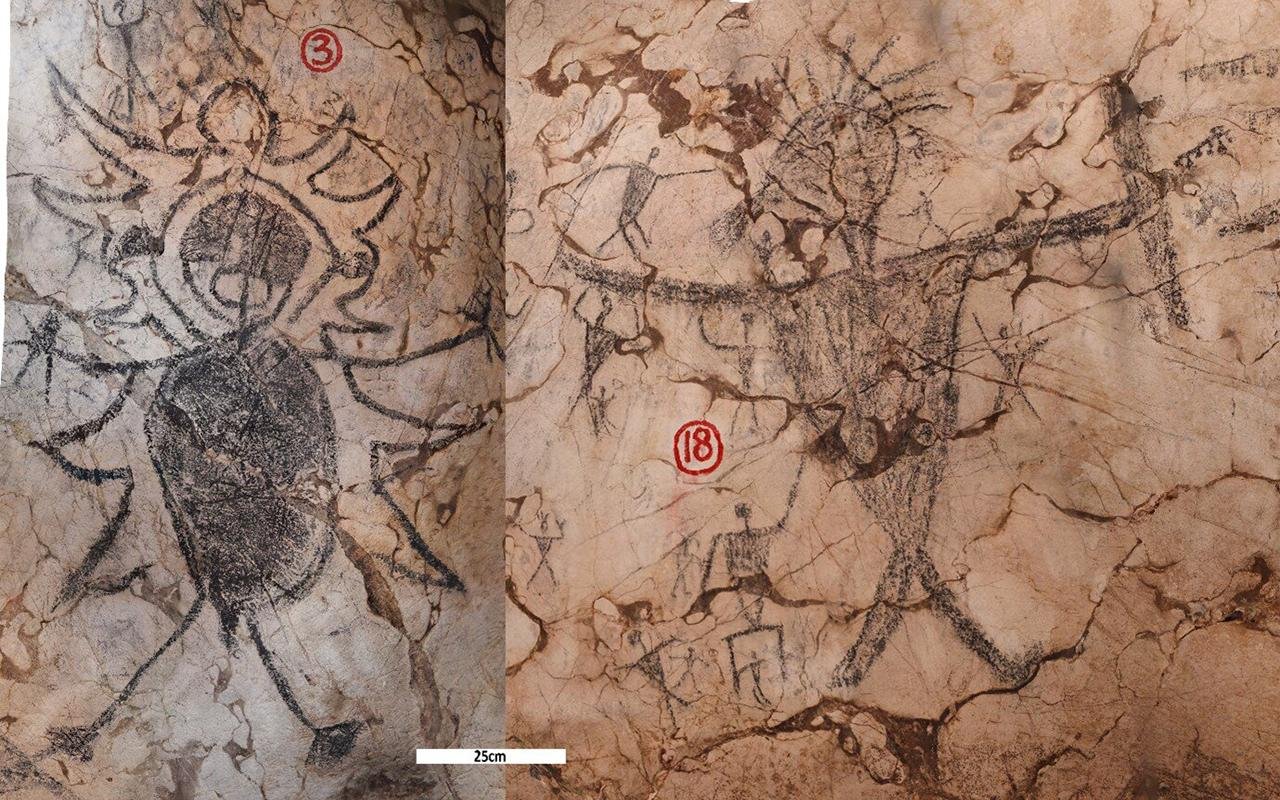

The drawings in Gua Sireh depict various scenes, including people wearing headdresses, some armed with shields, knives, and spears, engaged in activities such as hunting, butchering, fishing, fighting, and dancing. While prior research provided clues about their age, the precise dating has illuminated their historical context.

Mohammad Sherman Sauffi William, a curator at The Sarawak Museum Department and a descendant of the Bidayuh people, explained that the oral histories of the Bidayuh, who maintain custodial responsibilities over the site, helped inform the understanding of the dates.

The oral accounts recall the use of Gua Sireh as a refuge during territorial violence in the early 1800s when a Malay Chief demanded the Bidayuh hand over their children. Refusing to comply, the Bidayuh retreated to the cave, resisting a force of 300 armed men. While they suffered losses, the majority of the tribe escaped through a passageway at the back of the largest entrance chamber, preserving their children’s safety. The figures in the drawings are depicted wielding distinctive weapons, such as a Pandat and two short-bladed Parang Ilang, commonly used during warfare.

This research is part of a broader effort to understand the significance of this rock art in Southeast Asia and its role in documenting Indigenous histories and experiences.