Researchers have uncovered the fossilized remains of an ape species named Anadoluvius turkae, which may challenge the prevailing theory that the ancestors of African apes and humans evolved exclusively in Africa.

This finding suggests a potential European origin for hominines, a group that encompasses humans, African apes such as chimps and bonobos, and their fossil ancestors. While this discovery is intriguing, it’s important to note that it pertains to the common ancestor of hominines and not to the human lineage specifically.

Professor David Begun, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Toronto and co-senior author of the study emphasizes the distinction between the common ancestor of hominines and the human lineage. “Since that divergence, most of human evolutionary history has occurred in Africa. It is also most likely that the chimpanzee and human lineages diverged from each other in Africa,” he told Live Science.

The key discovery centers around an ape fossil found in Çorakyerler, central Anatolia, dating back 8.7 million years. This species, Anadoluvius turkae, is estimated to have weighed between 110 to 130 pounds, akin to a large male chimpanzee. The fossil’s surrounding context, including other animal remains like giraffes, warthogs, rhinos, and geological evidence, suggests that A. turkae inhabited a dry forest environment reminiscent of where early humans in Africa may have lived.

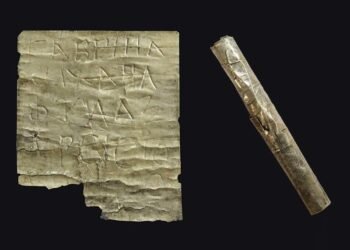

In this study, the scientists focused on a well-preserved partial skull unearthed at the site in 2015. This fossil includes most of the facial structure and the front part of the braincase, enabling a detailed analysis of evolutionary relationships. According to Professor Begun, this allowed them to reconstruct the face of an ancestor no one had ever seen before.

The researchers propose that A. turkae, along with other fossil apes like Ouranopithecus in Greece and Turkey and Graecopithecus in Bulgaria, constitutes a group of early hominines. This suggests that the earliest hominines may have originated in Europe and the eastern Mediterranean, specifically evolving from ancestors in Western and Central Europe.

However, this revelation raises questions about why hominines, if they originated in Europe, are not present there today, except for humans who arrived more recently. Additionally, it prompts inquiries about why ancient hominines did not disperse into Asia.

According to Professor Begun, evolution is unpredictable, shaped by a series of unrelated and random events. While it may not be immediately apparent why apes didn’t migrate from the eastern Mediterranean to Asia during the late Miocene, conditions in Africa might have been more favorable for such a dispersal.

Nevertheless, this study does not aim to assert that Eurasia played a primary role in human evolution; rather, it seeks to pinpoint the common ancestor of African apes and humans. Between 14 million and 7 million years ago, the ecological conditions in Europe, Asia, and Africa differed significantly, much like today’s regional variations. Understanding the ecological circumstances in which our ancestors evolved remains critical to grasping our origins.

Christopher Gilbert, a paleoanthropologist at Hunter College of City University of New York, acknowledges the significance of this discovery but highlights that recent comprehensive analyses of fossil great apes and early hominins do not align with the hypothesis of a European origin for hominines. Instead, they suggest that European apes branched off earlier than orangutans, making them distant relatives of living African great apes and humans.

Gilbert also emphasizes that a scarcity of hominine fossils in Africa during this period might be due to gaps in the African fossil record. He cites the paleontological axiom, “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence,” suggesting that the absence of fossils does not necessarily negate the possibility of hominine presence in Africa.

Professor Begun acknowledges the need for more evidence to definitively establish a connection between European and African hominines. Future fieldwork on both continents may provide additional insights into this intriguing aspect of human evolution.