New research provides compelling evidence that seaweed and freshwater plants were key elements of the prehistoric European diet, offering valuable insights into dietary practices from the Mesolithic period through the Neolithic transition and into the Early Middle Ages.

Scientists from the University of York and the University of Glasgow conducted an in-depth analysis of dental calculus from 74 individuals across 28 archaeological sites spanning from northern Scotland to southern Spain, presenting “direct evidence for widespread consumption of seaweed and submerged aquatic and freshwater plants.”

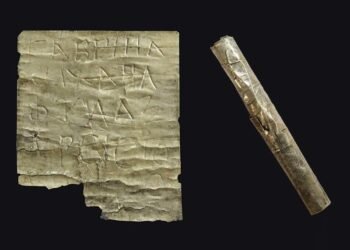

The study, published in Nature Communications, challenges the conventional belief that seaweed was mainly utilized for non-edible purposes such as fuel or fertilizers in ancient times. Dental calculus, the hardened plaque on ancient teeth, provided the researchers with a unique opportunity to explore the dietary habits of prehistoric Europeans.

“Today, seaweed and freshwater aquatic plants are virtually absent from traditional, western diets,” said Professor Karen Hardy from the University of Glasgow.

“Our study also highlights the potential for rediscovery of alternative, local, sustainable food resources that may contribute to addressing the negative health and environmental effects of over-dependence on a small number of mass-produced agricultural products that is a dominant feature of much of today’s western diet, and indeed the global long-distance food supply more generally.”

Seaweed, recognized for its nutritional value and sustainability, was a prominent component of the prehistoric European diet around 8,000 years ago, providing essential nutrients and protein. Researchers suggest that the decline of seaweed consumption coincided with the shift toward cereal crop cultivation, effectively ending its role as a dietary staple.

While seaweed is no longer a common dietary item in Europe today, there is growing interest in its nutritional benefits and sustainable production. The European Commission predicts that seaweed could offer more than 100 million tonnes of additional food by the 2040s. This revival could reintroduce seaweed as a dietary staple, continuing a tradition that dates back thousands of years.

The study also highlights the importance of historical dietary practices in reconstructing the past and the potential for forgotten local food resources to address modern health and environmental challenges. By studying the dietary components preserved in dental calculus, researchers can gain valuable information about the eating habits of ancient populations, paving the way for improved understanding and informed choices for the present and future.