Archaeologists in Pompeii have unearthed a prison bakery that exposes the harsh realities of ancient slavery in the Roman city. The bakery, located in Regio IX, insula 10, offers valuable information about the exploitation of enslaved individuals and animals who were confined to produce bread for the city’s inhabitants.

Pompeii, famously buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in CE 79, has revealed a residential home undergoing renovation during the catastrophic event. The site is divided into two distinct sections: one adorned with “refined frescoes,” and the other housing the shocking prison bakery. The latter is characterized by a confined space with small windows, barred with iron grates, allowing only limited light.

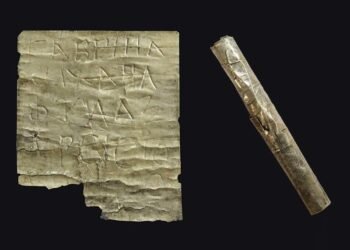

The enslaved workers, alongside a donkey, were imprisoned in the bakery to grind the grain necessary for bread production. The millstone area features semicircular recesses in the basalt flooring, revealing a coordinated movement of enslaved workers and blindfolded animals.

Pompeii Archaeological Park director, Gabriel Zuchtriegel, highlights the significance of this discovery, stating, “It is the most shocking side of ancient slavery, the one devoid of both trusting relationships and promises of manumission, where we were reduced to brute violence.”

Zuchtriegel emphasizes the importance of understanding the conditions faced by these enslaved workers, who played a vital role in supporting the city’s economy and contributing to the fabric of Roman civilization.

Moreover, the bakery’s location within a residential home undergoing renovations suggests that the property was not vacant at the time of the eruption. The discovery of three victims within the bakery further supports this notion.

The bakery-prison aligns with descriptions from Roman writer Apuleius, who, in the 2nd century CE, recounted the harsh conditions faced by enslaved individuals and animals working together in similar contexts.

Zuchtriegel notes, “It is a space in which we must imagine the presence of people of servile status whose owner felt the need to limit freedom of movement.”

The excavated space also reveals intentional carvings in the floor, likely designed to prevent animals from slipping and to guide them in a circular motion, resembling a clockwork mechanism. Zuchtriegel cites iconographic and literary sources, including reliefs from the tomb of Eurysaces in Rome, suggesting that a donkey and a slave typically worked together to move the millstone.

The findings complement an upcoming exhibition, “The Other Pompeii: Common Lives in the Shadow of Vesuvius,” set to open on December 15 at the Palestra Grande in Pompeii.

This exhibition aims to highlight individuals often overlooked by historical chronicles, including slaves who constituted the majority of the population and significantly contributed to the economy, culture, and social fabric of Roman civilization.