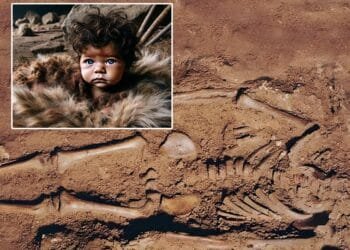

Archaeologists in 2017 unearthed a significant historical find in Cambridgeshire, England – the remains of a Roman slave who met a brutal end through crucifixion during the third or fourth century CE.

This extraordinary discovery has led to a comprehensive digital facial approximation. The project, featured on a BBC Four program titled “The Cambridgeshire Crucifixion,” showcases the intricate work of forensic artist Joe Mullins from George Mason University in Virginia.

The man, believed to be between 25 and 35 years old at the time of his death, was found buried in a cemetery alongside more than 40 others who displayed signs of rigorous manual labor. The skeleton is described as “battered” and unique due to the preservation of a nail in his heel.

“This man had such a particularly awful end that it feels as though by seeing his face you can give more respect to him,” Professor Corinne Duhig, an osteoarchaeologist from the University of Cambridge, who was part of the project, told the BBC. The reconstruction not only serves as a scientific endeavor but also aims to humanize an individual who lived more than 1,700 years ago.

The intricate process involved in reconstructing the man’s face began with Joe Mullins, who utilized CT scans of the skull and advanced computer software. Describing the process as “putting an ancient jigsaw puzzle together,” Mullins meticulously sculpted the facial muscles, guided by biomarkers and genetic information derived from the man’s DNA.

With a genetic profile compiled from the DNA, Mullins determined specific features, including the color of the man’s skin and dark eyes. The facial approximation not only brings forth the physical attributes but also serves as a poignant reminder of the humanity behind the ancient remains. Mullins shared, “One of the biggest surprises I always have while working on this kind of case is that this person was once a living human being.”

The Cambridgeshire Crucifixion documentary highlights that this man, only the second Roman crucifixion victim ever found globally, had a two-inch nail driven through his heel bone. Radiocarbon dating places his death between 130 CE and 337 CE, placing him in a Roman settlement between Cambridge and Godmanchester.

The documentary delves into the reasons behind such a brutal form of punishment, which was prevalent for both severe crimes and minor misdemeanors.

“He might have been a slave and committed some crime or misdemeanour — one that would not have resulted in crucifixion if he had been of higher rank,” Dr. Duhig told MailOnline in 2021. The victim’s status as a slave may have played a role in the harsh punishment meted out to him.

Crucifixions were not exclusive to those convicted of severe crimes; slaves could face this gruesome fate for seemingly minor infractions, underlining the harsh realities of Roman society. The documentary suggests that the Cambridgeshire man might have been involved in supplying materials and services to a local Roman settlement, making him vulnerable to punishment if he crossed those in power.

The facial reconstruction process, as narrated by Mullins, reflects the transformative nature of his work. “It’s like creating a portrait from the inside out,” he said. The completion of a facial approximation, for Mullins, occurs “when he sees a person staring back at him” on his computer screen.

The unveiling of the reconstructed face contributes to the broader understanding of Roman-era life in Britain. It also serves as a poignant reminder of the harsh realities of slavery and the diverse range of individuals who experienced the complexities of ancient societies.

Could it be that the Romans crucified those who committed crimes as a way of letting others know that if they misbehaved, this could happen to them? It’s a way of keeping people in line.