Researchers from the National Institute of Genetics, the University of Tokyo, and the Wakasa History Museum have conducted metagenomic analyses on coprolites excavated from the Torihama shell-mound site in Fukui Prefecture, Japan. The coprolites, dating back to the Early Jomon period, are estimated to be between 5,500 and 7,000 years old.

The findings revealed through DNA analysis of the coprolites, showcase the remarkable preservation of genetic materials from the digestive tracts of the Jomon people. Despite the age-related degradation of DNA, researchers successfully identified genetic fragments of viruses, such as human betaherpesvirus 5 and human adenovirus F. The study allows scientists to explore the co-evolution of bacteria and the viruses that infect them throughout history,

Luca Nishimura, Ituro Inoue, Hiroki Oota, and Mayumi Ajimoto, the researchers involved in the study, emphasized the significance of coprolites in providing insights into ancient cultures. They stated, “This data can help us to understand more details about culture and lifestyle in the past.”

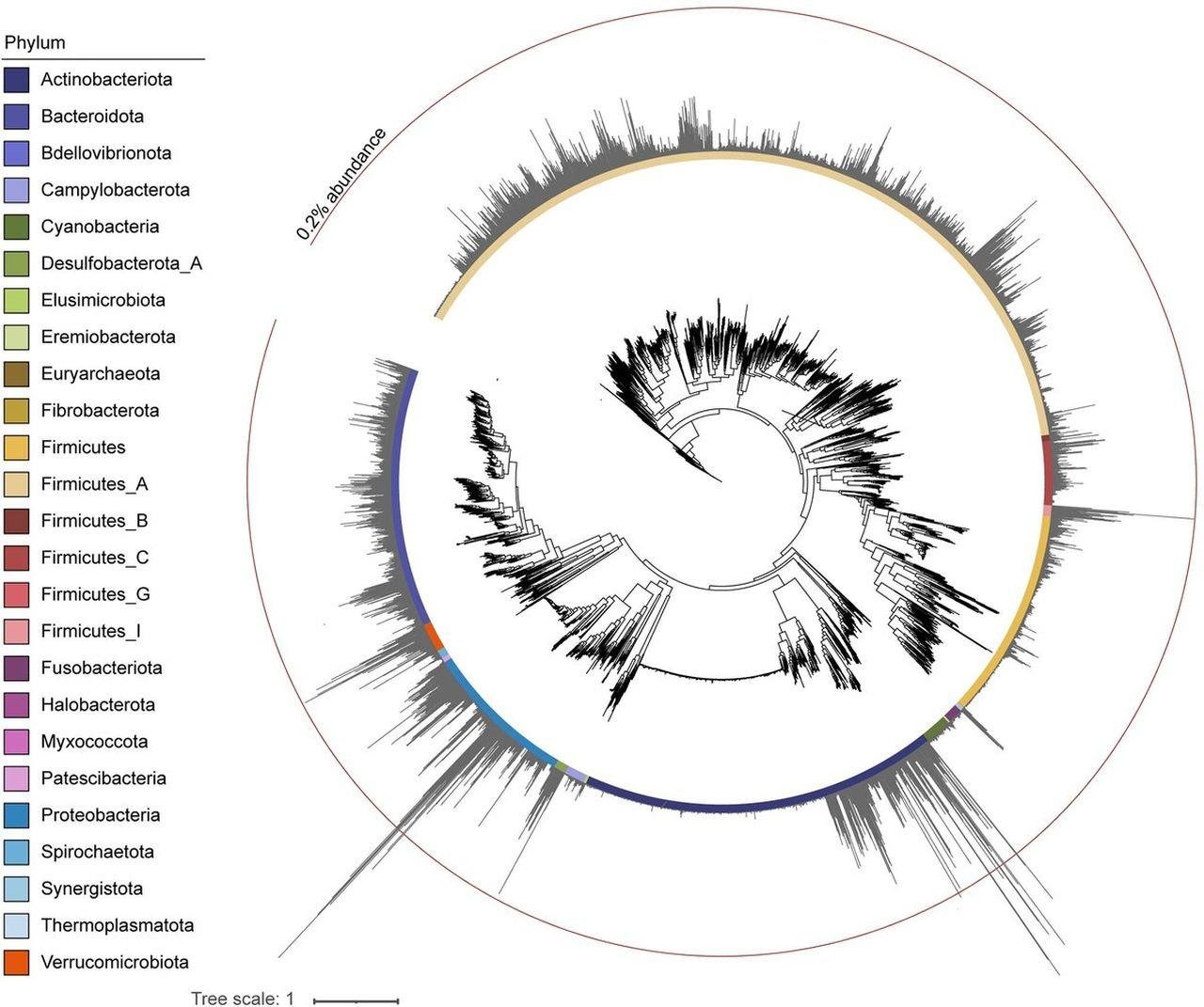

One key revelation from the study is that the gut contents of the ancient Jomon people closely resembled those of their modern descendants. The researchers compared the DNA remnants preserved in the coprolites with a library of modern DNA samples, finding similarities in the bacterial species and viral sequences. The gut viromes of present-day Japanese people share commonalities with the ancient Jomon gut environment, with viral sequences originating from Siphoviridae, Myoviridae, and Podoviridae families.

The coprolite analysis also sheds light on the dietary characteristics of the Jomon people. Through genomic information, the researchers identified the DNA of plant and animal species consumed by the ancient population, including Vigna angularis (red beans) and Oncorhynchus nerka (salmon), which continue to be dietary staples in the Fukui region to this day. Nishimura and the team noted, “Our findings provide genomic support that the Jomon people may have hunted and utilized salmon, possibly red salmon, as a food source.”

The study underscores the potential of coprolite analysis in unraveling long-term host-viral co-evolution trends. In a broader context, the research contributes to the growing field of microbiome analysis, which has implications for understanding the health and lifestyles of ancient populations.

The significance of this research extends beyond the historical context, as microbiomes, comprising bacteria, viruses, and fungi, play a crucial role in various aspects of human health. Recent studies, such as one published in Nature Microbiology, have connected the diversity of gut microbiomes to conditions like auto-immune disorders, obesity, and kidney stones. Understanding the long-term evolution of these microbial communities provides valuable information about human health and dietary patterns.