Researchers from the University of Exeter have recently completed a comprehensive study shedding light on the early inhabitants of the Amazon Basin. Their investigation, part of the €2.5m European Research Council-funded LASTJOURNEY project, centered on rock shelters in northwest Colombia, which served as homes to some of the earliest migrants to South America approximately 13,000 years ago.

These early settlers, facing the challenges of dense rainforest and acidic clay-based soils, established themselves in shallow cave dwellings, where they engaged in a variety of domestic and ritual activities. Mark Robinson, Associate Professor of Archaeology at the University of Exeter, said: “The ‘peopling’ of South America represents one of the great migrations of human history – but their arrival into the Amazon biome has been little understood.”

The excavation efforts, led by the UE team, have not only pushed back the estimated timeline of human occupation but have also provided novel information about the daily lives and historical trajectories of these ancient peoples.

The study focused on two rock shelters in the Serranía La Lindosa region, situated on the fringes of the Amazon and Orinoco basins. Through meticulous analysis of soil sediments both within and outside the shelters, researchers were able to discern patterns of human activity spanning millennia. Traces of stone tools, charcoal, and organic matter revealed evidence of food preparation, consumption, and disposal, alongside periods of abandonment lasting over a millennium.

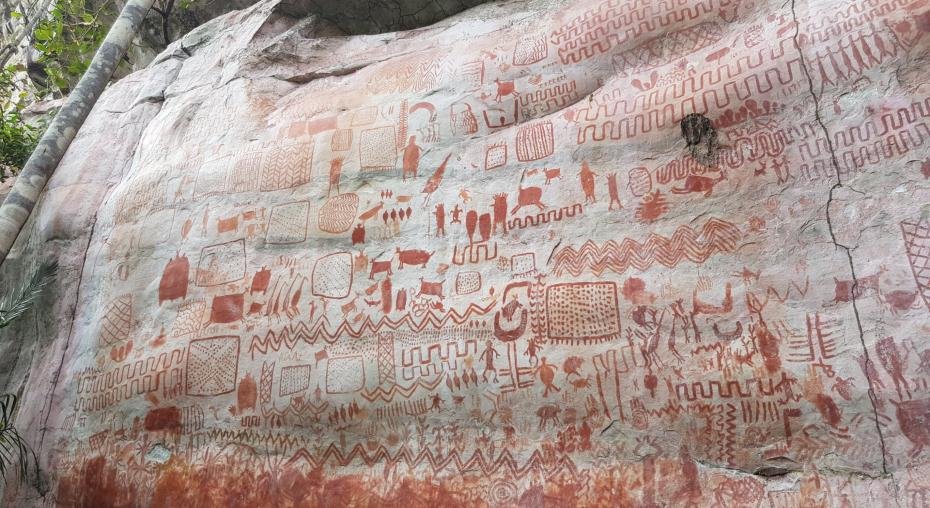

José Iriarte, Professor of Archaeology at Exeter, highlighted the attractiveness of the region to early forager groups, citing its abundant resources, including palm-dominated tropical forests, savannahs, and riverine areas. These shelters, strategically located to offer protection and visibility, served as hubs for various activities, from food procurement to artistic expression.

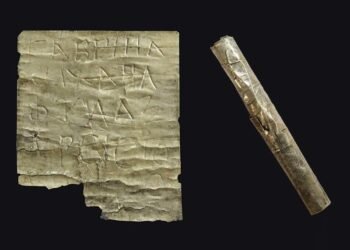

The presence of ceramics dating back approximately 3,000 years, along with evidence of soil cultivation from 2,500 years ago and traces of maize cultivation 500 years ago, underscores the long-term occupation and adaptation of these sites by successive generations. Ongoing research endeavors aim to further explore the rich array of artifacts recovered, including animal bones, plant remains, and ochre paintings.

Dr. Jo Osborn, Postdoctoral Research Associate, said: “All of the rock shelters exhibit ochre paintings from the earliest occupations,” she noted, suggesting that these pioneers were not only surviving but also actively documenting and interpreting their encounters with this new environment.

The findings of this study, published in Quaternary Science Reviews, offer a compelling narrative of human resilience and ingenuity in the face of challenging environmental conditions.