The Bronze Age Mycenaeans, renowned for their impressive architecture and legendary roles in Homeric epics, have long been a subject of study. One of their most notable technological achievements, the Dendra armor, has recently been the focus of an extensive study to determine its practicality and effectiveness in battle.

The armor, discovered in 1960 near the village of Dendra, has been scrutinized for decades, with debates centered on whether it was purely ceremonial or genuinely used in combat. A recent study conducted by researchers from the University of Thessaly in Greece and the University of Birmingham in the UK has provided compelling evidence supporting the latter.

The research, led by Andreas Flouris, a professor of physiology at the University of Thessaly, aimed to test the combat effectiveness of the Dendra armor through a rigorous simulation based on historical accounts, particularly those from Homer’s “The Iliad.” This epic poem, while largely considered a work of fiction, provides detailed descriptions of Bronze Age warfare, which the researchers used to create a realistic combat simulation.

Thirteen volunteers from the Hellenic Armed Forces’ marines were recruited to don replicas of the Dendra armor and participate in an 11-hour combat simulation. The replicas were meticulously crafted to match the original armor, made of hammered bronze plates and dating back to the 15th century BCE. The armor weighed approximately 51 pounds (23 kilograms) and was made using a blend of copper and zinc to closely resemble the original materials. Additionally, a replica of a Mycenaean cruciform sword was created, along with other weapons such as spears and stones, to enhance the authenticity of the simulation.

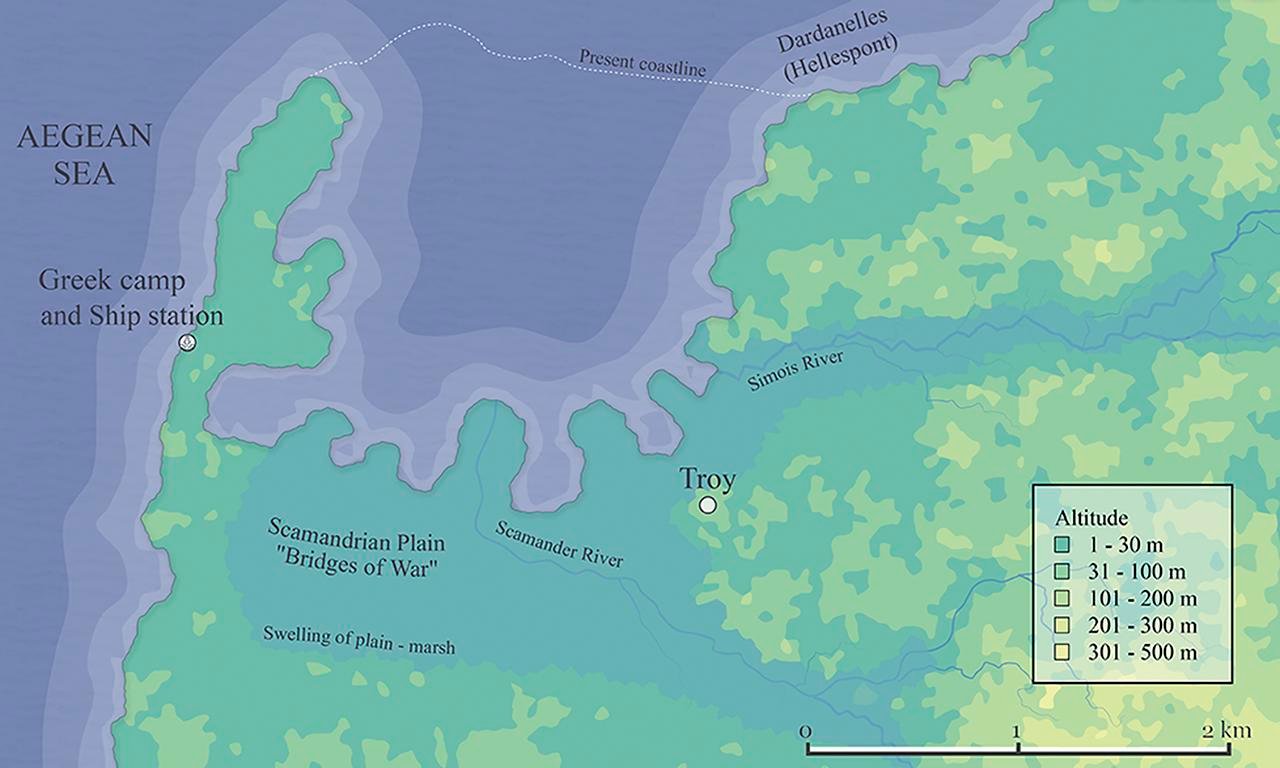

The combat protocol was designed to mimic the daily activities and environmental conditions of Late Bronze Age warriors. The researchers used paleoclimate data to recreate the climate of Troy, which was estimated to be around 64 to 68 degrees Fahrenheit (18 to 20 degrees Celsius) with an annual relative humidity of 70% to 80%. The volunteers followed a diet similar to that of a Mycenaean soldier, consisting of bread, beef, goat cheese, green olives, onions, and red wine, providing them with nearly 4,500 kcal per day.

Throughout the simulation, participants engaged in various combat scenarios including duels, foot warrior versus chariot, distance encounters, and chariot versus ship battles. The researchers recorded the volunteers’ heart rates, core body temperatures, average skin temperatures, and energy expenditures to assess the physical demands of wearing the armor. Despite signs of fatigue and soreness, the volunteers successfully completed the regimen, indicating that the armor did not hinder their fighting abilities or cause severe strain.

The study, published in the journal PLOS ONE, concluded that the Dendra armor was indeed suitable for extended combat. “The efficacy and variety of Mycenaean swords and spears have long been recognized,” said Flouris and his colleagues. “The addition of ‘heavy’ armor will have given elite Mycenaean warriors considerable advantages over those with a shield only for defense or with the lighter ‘scale’ armor in use in the Middle East.”

Co-author Ken Wardle from the University of Birmingham added that the armor wearers exhibited high-intensity interval exercise, characterized by periods of intense effort followed by rest, much like Homeric descriptions of combat. This suggests that the Mycenaean warriors could have sustained prolonged engagements on the battlefield, retreating periodically to recover and eat, as described in “The Iliad.”

Barry Molloy of the University College Dublin acknowledged that while Homer is not always considered a reliable source for Bronze Age warfare, the rigorous protocols used in this study are significant for understanding the practical use of the armor.

The study also introduced a computer-based mathematical model to simulate combat conditions, allowing for further testing of the armor’s effectiveness in various scenarios. This software, made freely available, aims to enhance the understanding of Mycenaean combat technology and its evolution into the Iron Age.

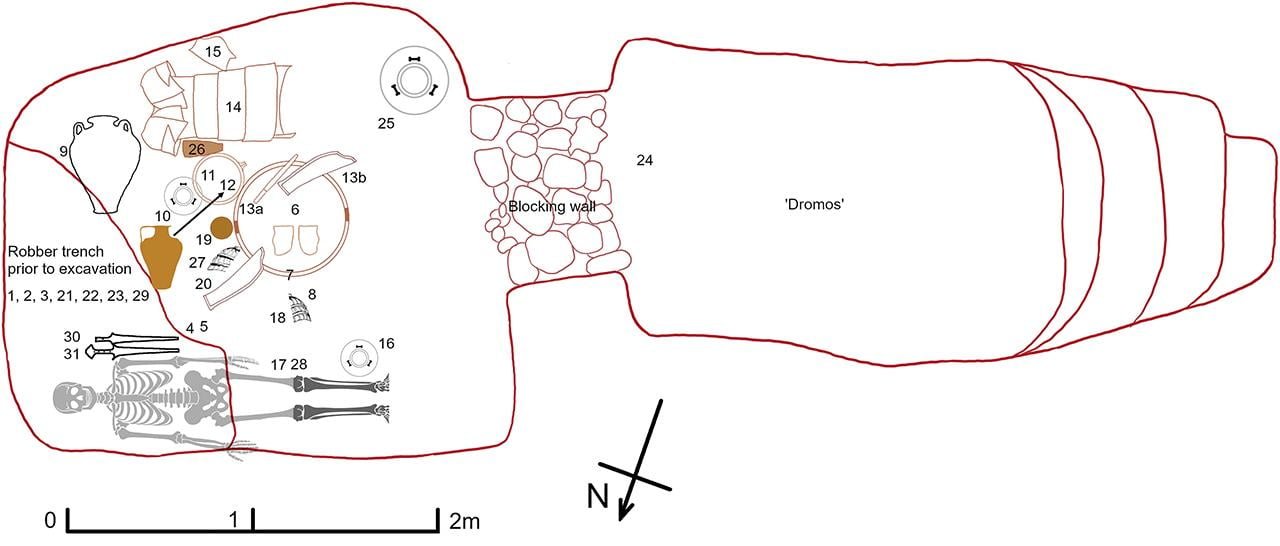

Researchers suggested that the findings could help interpret other similar artifacts, such as those found in the Griffin Warrior Tomb in Greece.