Researchers have revealed two infant burials beneath a prehistoric monument known as a dragon stone, or Vishapakar, at the Lchashen site near Lake Sevan in Armenia.

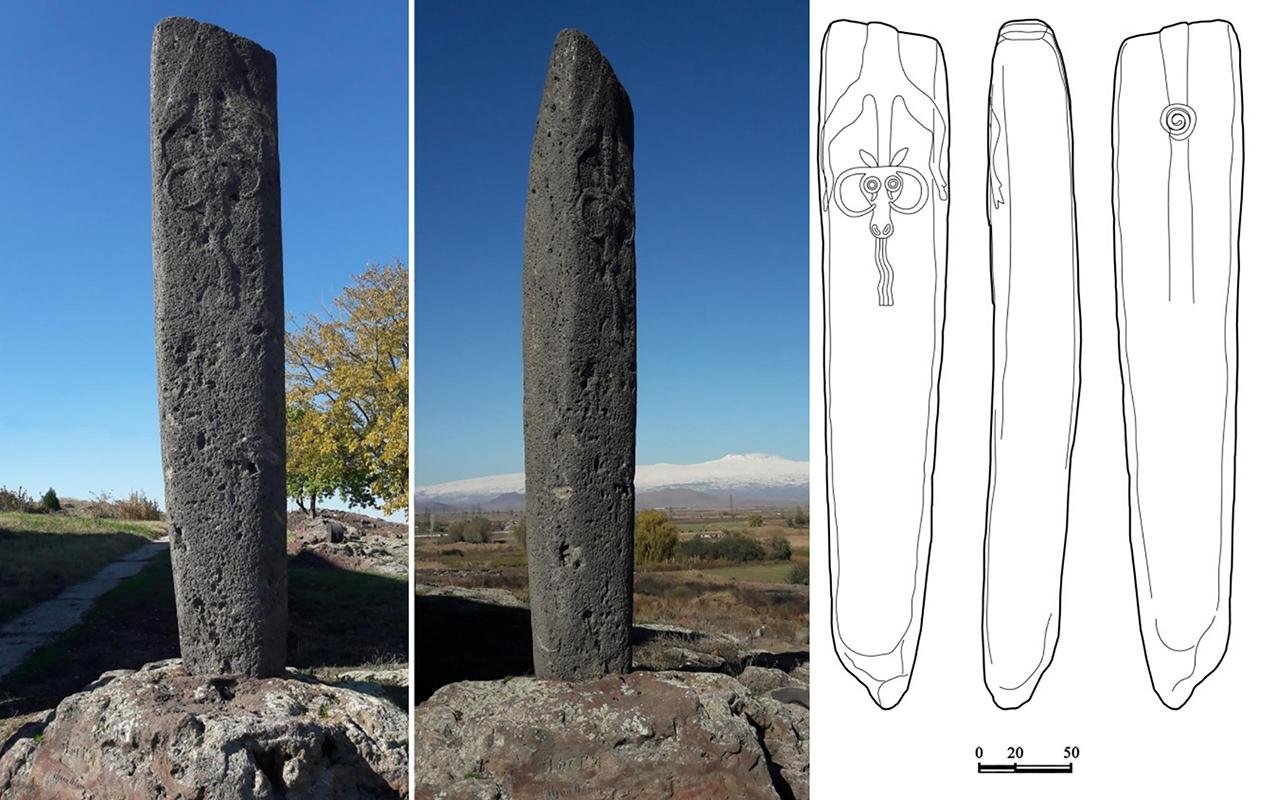

Dragon stones are prehistoric basalt stelae adorned with animal imagery such as fish heads or serpents. Found primarily in the Armenian Highlands, these monoliths are associated with Armenian folklore, representing vishaps—mythical water dragons believed to be guardians of water and thunder. Researchers have documented around 150 dragon stones, most of which are located in water-rich mountain meadows at altitudes between 6,500 and 10,000 feet. These stones vary in height from 150 cm to 550 cm (59 to 216.5 inches) and are thought to have been commemorative monuments placed at the center of open-air sanctuaries.

The stones are typically found near springs or canals, suggesting a ritual connection with water. This connection is evident in the carvings of animals, particularly fish and bovids (such as goats, sheep, and cows), which are believed to symbolize the vishaps.

In 1980, during construction work near an ancient cemetery in the village of Lchashen, workers discovered a dragon stone more than 11 feet high, decorated with the image of a sacrificed bovid. Excavations revealed a burial pit beneath this stone, dating back to the 16th century BCE. This burial site is unique among the hundreds of graves excavated in the region because it is the only one marked by a dragon stone and one of the very few that contained infant remains.

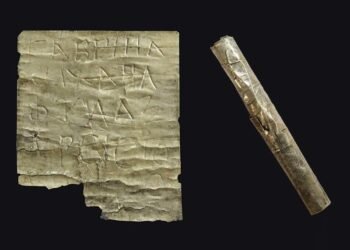

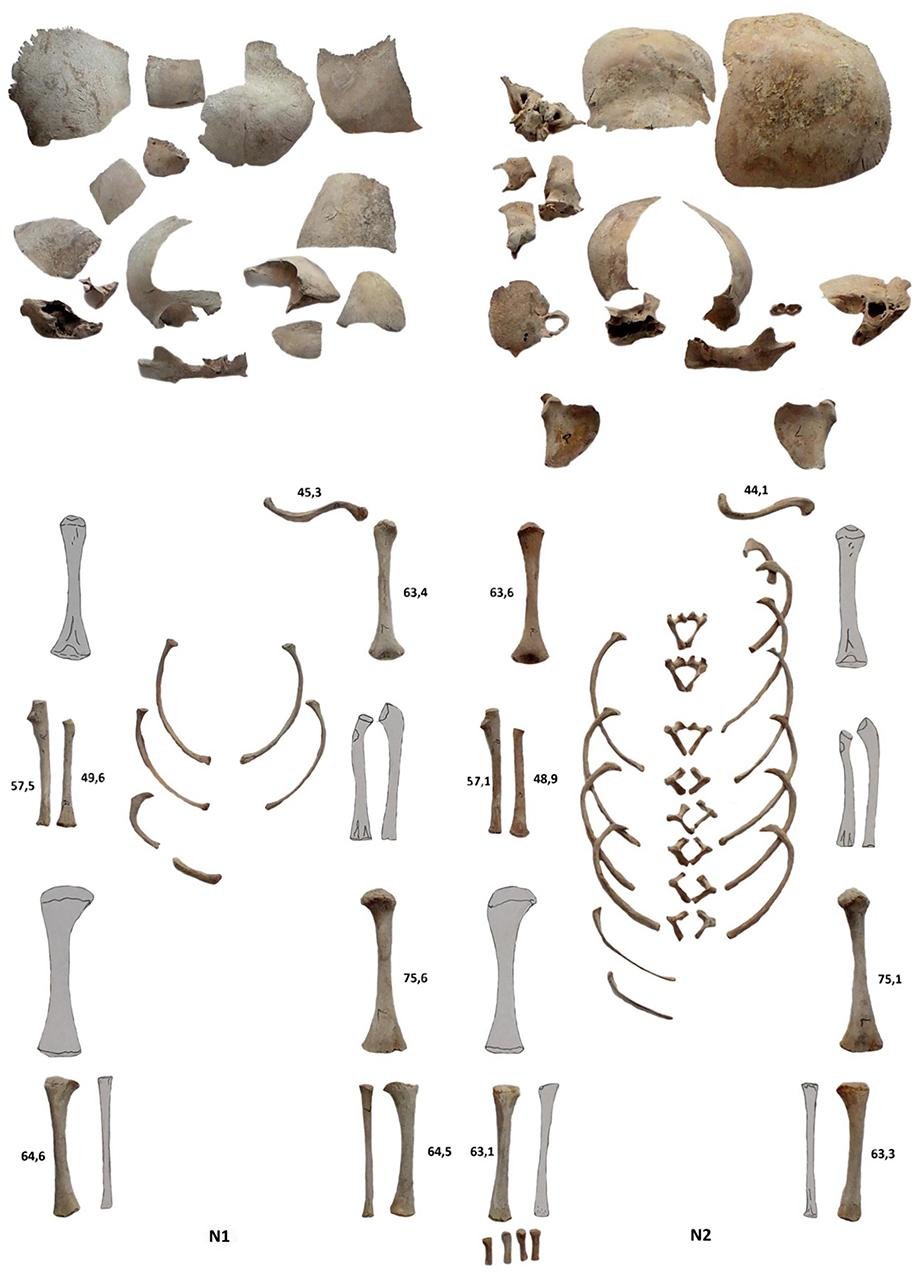

The burial pit contained the remains of two infants, known as Dragon1 and Dragon2, along with archaeological artifacts such as painted pottery, a bronze hairpin, a carnelian bead, a bone needle, a fragment of obsidian, and human bones of an adult woman. Initial analyses of these remains were conducted in the 1980s, but it wasn’t until recently that detailed genetic testing was performed.

The ancient DNA analyses revealed that the two infants were second-degree relatives with identical mitochondrial sequences, indicating a close familial relationship. This finding suggests possible biological relations such as half-sisters, aunt-niece, double-cousins, or grandparent-grandchild. However, researchers propose that the most likely relationship is either that the two babies were aunt and niece, or they were half-siblings born to the same mother through heteropaternal superfecundation—a rare phenomenon where a woman becomes pregnant with two babies from different fathers at the same time.

The presence of infant remains under such a significant monolith raises questions about the funerary practices and beliefs related to death and the afterlife in Bronze Age Armenian society. The burial context, combined with the monumental dragon stone, suggests a possible ritual or symbolic significance that is not yet fully understood.

“In Late Bronze Age Armenia in general and at Lchashen in particular, burials of children are rare, and the burial of two newborns combined with a monumental stela is unique,” stated the study authors. They also noted that in the South Caucasus, stelae were sometimes used to mark graves, but out of 454 Bronze Age graves excavated at Lchashen, only this one was marked with a dragon stone.

The sacrificed bovid carved on the dragon stone could symbolize a cultural death rather than a natural one. Researchers suggest that the burials might have been the result of a difficult birth or a sacred killing, although no direct traces of violence were detected on the fragile infant remains.

This discovery has broader implications for understanding the role of dragon stones in Bronze Age funerary practices. The association between these monuments and burials suggests that dragon stones may have had a funerary or ritualistic role beyond mere decoration or commemoration.