For decades, the narrative surrounding Easter Island, or Rapa Nui, has been one of ecological disaster. It was widely believed that the island’s early inhabitants depleted their resources, leading to environmental collapse and a dramatic reduction in population. However, recent research revealed that the island’s population was never as large as previously thought and that its people demonstrated remarkable resilience and ingenuity in their agricultural practices.

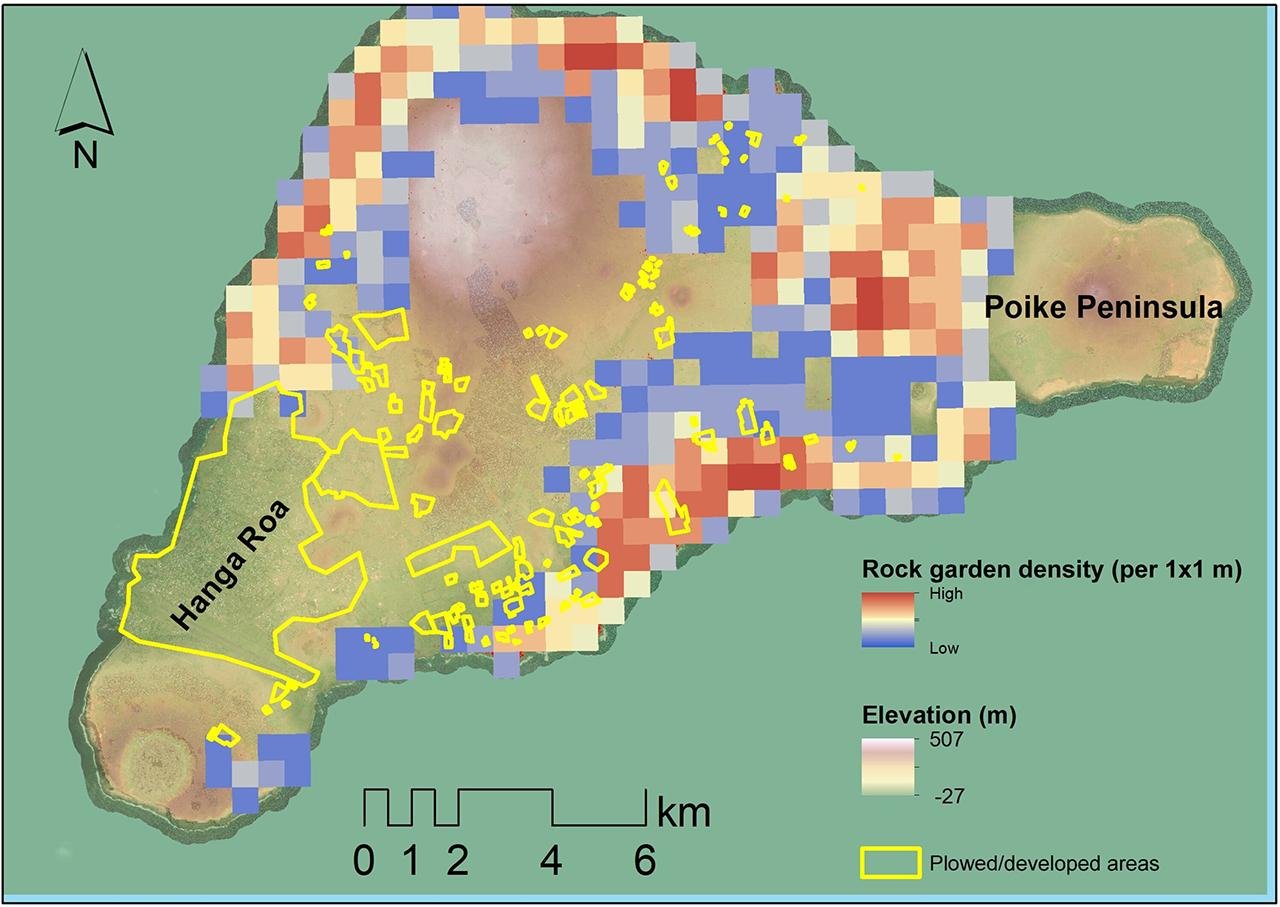

A team of researchers, including faculty from Binghamton University and Columbia University, conducted an in-depth analysis of Easter Island’s rock gardens to reassess the island’s pre-contact agricultural output and population size. The study, published in Science Advances, was co-authored by Binghamton University’s Professor Carl Lipo, Environmental Studies Research Development Specialist Robert J. DiNapoli, and post-doctoral fellow Dylan S. Davis, along with other collaborators.

Easter Island, formed from volcanic eruptions a million years ago, has inherently infertile soils due to the erosion of essential nutrients like potassium, phosphorus, and nitrogen, as well as the impact of oceanic salt spray. “Rapa Nui’s soils were never highly fertile,” explained Lipo. “The island’s first settlers had to adapt to these limitations.”

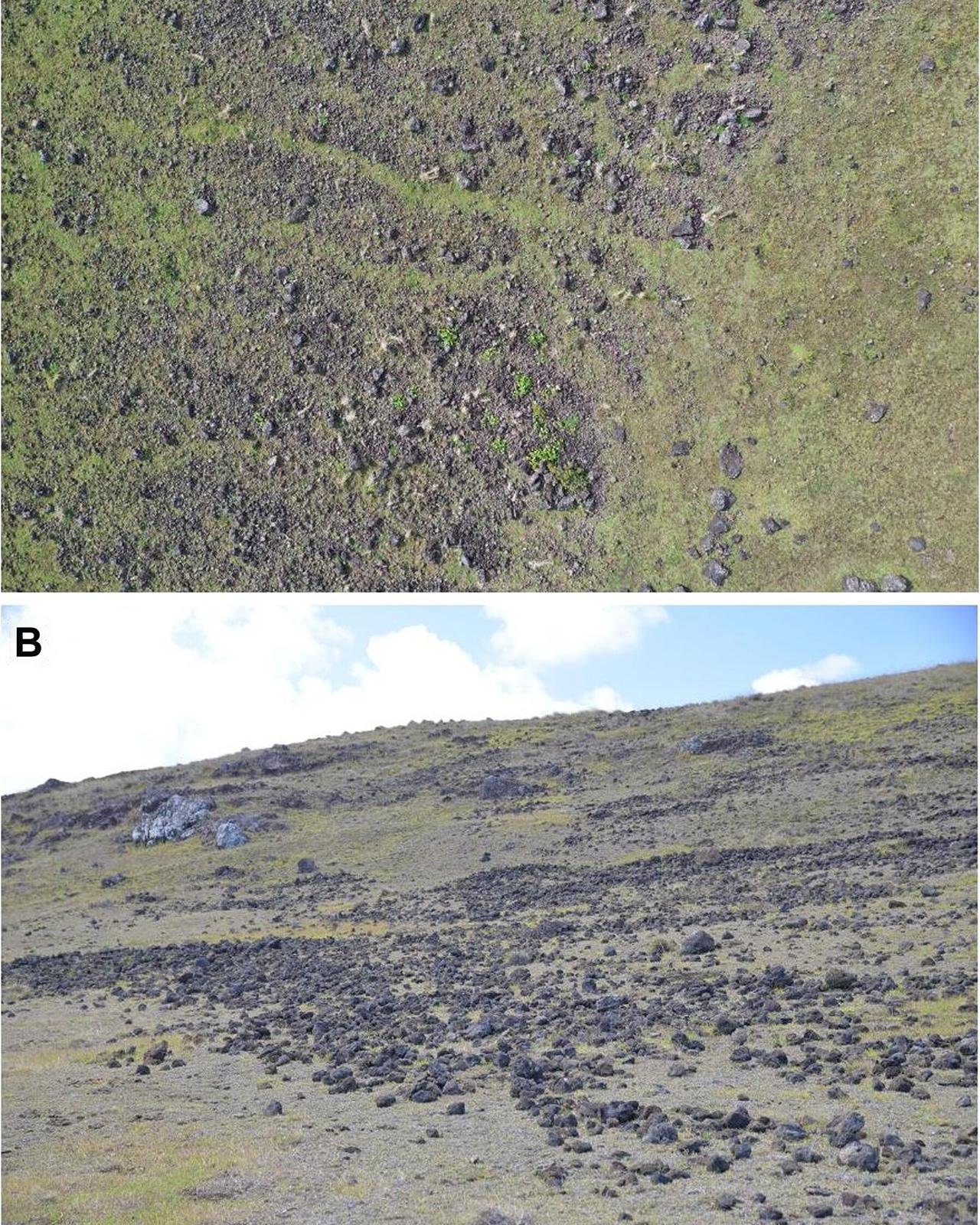

Initially, the islanders employed slash-and-burn techniques to enrich the soil, but this led to deforestation. They subsequently turned to composting plant waste and utilizing rock mulch to enhance soil fertility. While composting alone was insufficient to sustain agriculture, rock mulch proved effective, albeit labor-intensive. Islanders manually broke off pieces of bedrock and mixed them with soil, thereby enhancing nutrient levels and preventing erosion.

Rock mulching, a method used by other cultures, including the Maori in New Zealand and indigenous peoples in the American Southwest, involves breaking rocks into small particles to expose more surface area for nutrient release. “Modern agriculture uses machines to crush rocks into small particles, which exposes more surface area,” Lipo said. “Rapa Nui inhabitants did this manually, breaking rocks and incorporating them into the soil.”

The primary crops grown in these rock gardens included dry-land taro and yams, but sweet potatoes, with numerous varieties, were the mainstay, according to DiNapoli. Early European visitors estimated that rock gardens covered 10 percent of the island. However, previous studies using satellite imagery misidentified various features, such as roads, as gardens.

Dylan Davis used shortwave infrared (SWIR) satellite imagery and machine learning to produce a more accurate estimate, revealing about 180 acres of mulched land, significantly less than previously thought. SWIR imagery, typically used for geological mapping, can distinguish between different mineral compositions and moisture levels, helping rock gardens stand out more distinctly from the surrounding terrain.

Based on the revised garden area, researchers estimated that around 3,000 people lived on Rapa Nui at the time of European contact. Early European accounts suggesting a population of 3,000 to 4,000 align with archaeological findings, Lipo said. “The island’s ecological constraints meant it could never support a large population,” Davis stated. “The inhabitants adapted their environment to maximize agricultural yield, but the population remained relatively small. This case illustrates sustainable adaptation rather than ecological collapse.”

The misconception about the island’s population size partly stems from the impressive moai statues and the assumption that large workforces were needed to build them. “We should not simplify Easter Island’s history to fit convenient narratives,” Lipo said. “Understanding the island within its own ecological context reveals a different story than what has been popularly believed.”

Carl Lipo emphasized that the research provides credit to the Rapa Nui people for their ingenuity in surviving on the island. “You know, 14 by seven miles doesn’t give you a lot of different things you could do with it, but they made the most of what they had,” Lipo told reporters. “Europeans when they arrived to this island were bewildered by the fact that there were spectacular statues and very few numbers of people. They assumed that in order to move these gigantic statues, there must have been much larger populations. Really that’s a European perspective.”

Easter Island’s case is often misused as an example of ecological failure, Lipo noted. “Ecologists often continue to use Rapa Nui as a case study for collapse and ecological failure. They use it for modeling and for policy setting over and over again, which we think is really misguided. Easter Island is a great case of how populations adapt to limited resources on a very finite place and how they did so sustainably.”