Archaeological excavations led by the National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research (Inrap) have unearthed a necropolis for stillborn and young children in Auxerre, France. Situated in the historic center of the city, the site dates back to the 1st to 3rd centuries and is part of the larger necropolis of Roman Autessiodurum.

Since February 2024, under the guidance of the State (DRAC Bourgogne–Franche-Comté), Inrap archaeologists have been conducting detailed excavations at Place du Maréchal Leclerc in Auxerre. The fortified town of Autessiodurum, founded by the Gallic Senones people in 30 BCE, became a provincial capital under Roman rule by the 3rd century. The new fortifications in the 4th century enclosed the town, covering what is now identified as a necropolis for young children and stillborns.

This necropolis is distinct in several ways. According to ancient customs, necropolises were typically located outside city boundaries. The burial ground in Auxerre adhered to this tradition but featured many unique characteristics that set it apart from contemporaneous sites. Notably, the necropolis was specifically designated for infants and stillborns, reflecting the high mortality rates among young children during this period.

Excavations revealed that burials were performed with great care and involved complex, multi-stage funerary rituals. Up to eight stages have been observed, underscoring the intricate nature of these rites. Most of the infants were interred in fetal positions, though some were laid on their backs.

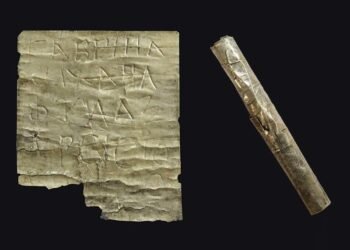

The containers used for burials varied widely, including ceramic vessels, wooden coffins, tree bark, stone caskets, textiles, and other soft materials. In several instances, bodies were covered with fragments of amphora or long curved roof tiles (imbrex) to protect them. One notable grave was marked with a stone engraved with a rosette.

The archaeological team discovered numerous broken ceramic dishes near the burials, which were likely used for offerings to the dead and the gods. Such practices are consistent with Gallo-Roman traditions, where funerary offerings were meant to serve the deceased in the afterlife.

According to Inrap’s statement, “To protect these young deceased people, objects intended for protection in the afterlife (called ‘apotropaic’ or ‘prophylactic’) accompany them, such as a pearl, a coin, a spindle. A miniature ceramic cup was also placed at the head of a young child.”

These protective objects varied, including beads, coins, small jewelry, and miniature ceramic goblets, all intended to safeguard the deceased in their journey to the afterlife. The presence of these items indicates that, despite the high mortality rate among infants, there was significant care and attention given to their burials.

One of the most striking findings is the high density and overlapping nature of the burials. Up to five levels of tombs have been identified, a feature that is unique in the Gallo-Roman world, where maintaining the integrity of each tomb was typically prioritized. This overlapping suggests a scarcity of burial space, necessitating the reuse of areas and the superimposition of graves. This practice could also reflect the societal status of the deceased children, who may not have been perceived as full individuals in their own right.

The discovery in Auxerre aligns with similar findings in other recent excavations, such as those in Narbonne. The site’s excellent state of preservation provides archaeologists with a unique opportunity to study these ancient practices in depth.