In a new study published in the journal PLOS ONE, Brazilian researchers from the University of São Paulo’s Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology (MAE-USP) have revised the historical narrative of human occupation along Brazil’s coast.

This research, involving collaboration with scientists from the United States, Belgium, France, and various Brazilian states, brings fresh perspectives on the ancient sambaqui builders at the Galheta IV archaeological site in Laguna, Santa Catarina.

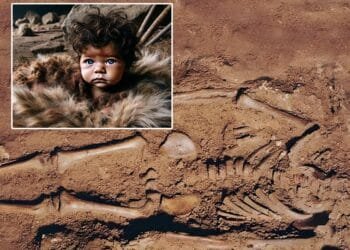

Sambaquis, also known as shell middens, are ancient mounds consisting of layers of shellfish debris, human and animal bones, plant remains, and various artifacts. These structures serve as evidence of long-term human occupation and were used for burial, shelter, and territorial demarcation. The builders of these mounds, the sambaquieiros, were previously thought to have been replaced by the Southern Jê ancestors. However, the new findings challenge this assumption.

The theory that one ethnic group replaced the other arose partly because sites like Galheta IV mark the end of sambaqui building. André Strauss, a professor at MAE-USP and a key author of the study said, “There was far less interaction than has been thought between these midden builders and the proto-Jê populations. Their funerary practices and pottery were different, and the sambaquieiros lived there from birth and were descendants of people who had lived in the same place.”

This new perspective emerged from an extensive analysis of archaeological evidence, including the re-examination of materials collected between 2005 and 2007. Jéssica Mendes Cardoso, the study’s lead author, quantified isotopes from strontium, carbon, and nitrogen in human remains, revealing that fish and other seafood comprised 60% of the group’s diet. Additionally, the analysis showed that these individuals were not cremated, a practice typical among Southern proto-Jê populations.

The Galheta IV site offers unique insights into the ancient coastal inhabitants. Among the findings were faunal remains, such as bones of marine birds like albatrosses and penguins, and mammals such as fur seals. “These animals were not part of their daily diet but were consumed seasonally or possibly kept at the site. They were likely part of their funeral rites since no one lived in this place. The site was a burial ground,” Cardoso explains. For example, one burial unit contained the remains of 12 albatrosses.

The study provided new dating for the site, estimating it was active between 1,300 and 500 years ago, rather than the previously thought 1,170 to 900 years ago. The analysis of pottery found at the site also suggests that the proto-Jê influence was more a matter of cultural exchange than population replacement. Out of 190 potsherds excavated, 131 were large enough for detailed examination. The pottery’s design differed significantly from that of the upland proto-Jê but was similar to other coastal sites, indicating coastal cultural diffusion.

Fabiana Merencio, a co-author of the study and postdoctoral fellow at the Federal University of Santa Catarina, remarks, “The pottery is very different from that found in the Santa Catarina uplands, in terms of shape and decoration, but similar to that found at other coastal sites on both the north and south of the state. These are the oldest pottery remains found in the state, dating from 1,300 years ago, whereas the pottery found in the uplands is about 1,000 years old.”

The study suggests that the observed changes in material culture and settlement patterns were likely due to environmental and cultural factors, such as changing sea levels and interactions with other groups, rather than a complete population replacement.

Verônica Wesolowski, an archaeologist and professor at MAE, notes, “We have no evidence of a population exchange. The replacement would be the disappearance of a biological unity from the cultural forms associated with it. The population of Galheta IV is closely related to the ancient sambaqui people, but the material culture seems to have more similarities with the Jê population.”

This comprehensive approach, incorporating isotopic analysis, zooarchaeology, and pottery examination, underscores the complexity of human interactions and adaptations in prehistoric coastal Brazil.

Looking forward, a new research group led by Ximena Villagran, a professor at MAE-USP, plans to explore another site, Jabuticabeira II, to further investigate these historical dynamics.