Recent archaeological research has provided compelling evidence that Anglo-Saxon warriors from sixth-century Britain participated in Byzantine military campaigns in the eastern Mediterranean and northern Syria. The findings, supported by artifacts from prominent Anglo-Saxon burial sites, suggest a previously unrecognized international dimension to their history.

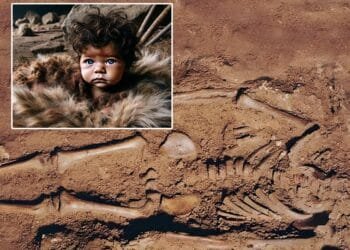

One of the most significant pieces of evidence comes from the renowned Sutton Hoo site in Suffolk, where a 27-meter-long ship burial, one of the UK’s most spectacular archaeological finds, was unearthed. This site yielded a treasure trove of artifacts, including Byzantine silverware and items that could not have arrived in Britain solely through conventional trade routes. Among these discoveries were objects such as Sasanian personal seals and silver drachms, which Dr. St John Simpson, a senior curator at the British Museum, argues challenge the simplistic view that all non-local goods found in Britain came through trade.

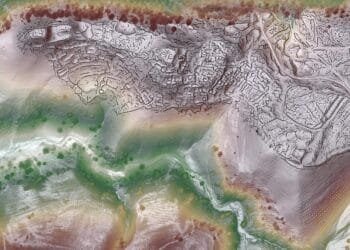

Dr. Simpson, along with Helen Gittos, a medieval historian from Oxford University, has meticulously analyzed the exotic items excavated at Sutton Hoo, Taplow, and Prittlewell. They have concluded that these artifacts likely originated from the eastern Mediterranean and northern Syria. The presence of these items suggests that Anglo-Saxon warriors had been involved in Byzantine military campaigns against the Sasanian Empire, a powerful Iranian dynasty that controlled vast territories.

In an interview with the Guardian, Simpson noted, “The eastern connections of the warrior tunics at Prittlewell and Taplow, coupled with the design of the shoulder clasps from Sutton Hoo, strengthen the idea that these individuals returned from Syria aligned even more closely with the late antique fashions of Byzantine-Sasanian elite warrior society.”

At Taplow in Buckinghamshire, archaeologists discovered the remains of a man wearing a Eurasian-style riding jacket, a distinctive and unusual form of dress. Meanwhile, the Prittlewell burial chamber in Essex yielded a copper flagon adorned with a unique pearl roundel depicting St. Sergius in a Sasanian-style roundel. This iconography firmly places the flagon within a Sasanian design language, suggesting it was crafted in a Sasanian workshop.

“These finds put the Anglo-Saxon princes and their followers center-stage in one of the last great wars of late antiquity,” Simpson explained. “It takes them out of insular England into the plains of Syria and Iraq in a world of conflict and competition between the Byzantines and the Sasanians and gave those Anglo-Saxons literally a taste for something much more global than they probably could have imagined.”

Another intriguing find was the presence of bitumen lumps at Sutton Hoo, previously assumed to be connected with the ship’s caulking. However, scientific analysis has shown that these bitumen lumps originated from a specific source in northeast Syria. The Sasanians used bitumen in the lining of pottery and for its perceived medicinal properties. Simpson suggested, “I think that’s another item that’s been brought back with perceived or real curative power by superstitious warriors who’ve possibly even converted to Christianity on effectively Byzantine crusades against the Sasanians.”

The evidence gathered by Simpson and Gittos points to Anglo-Saxon warriors serving under Byzantine emperors Tiberius II and Maurice, who recorded in his military handbook that “Britons” were skilled fighters in wooded areas. This involvement likely stemmed from a combination of adventure and the prospect of pay, as the Byzantines were known to recruit mercenaries from across Western Europe to bolster their mobile armies.

Helen Gittos stated: “This opens up a startlingly new view onto early medieval British history.” The discoveries suggest that the Anglo-Saxon elite were not only aware of but actively participated in the broader geopolitical and military conflicts of their time, far beyond the shores of Britain.