Archaeological research at the renowned Mesolithic site of Star Carr in North Yorkshire has revealed an unexpected level of organization and sophistication in the living spaces of hunter-gatherers. A collaborative team from the University of York and the University of Newcastle has uncovered evidence suggesting that these early inhabitants maintained orderly homes by designating specific areas for various domestic activities.

Located at the eastern end of the Vale of Pickering near Scarborough, Star Carr is one of the most significant Mesolithic sites in Europe. During prehistoric times, it was situated near the outflow of a palaeolake known as Lake Flixton. Today, the site offers invaluable evidence of early British dwellings and some of the earliest known architecture.

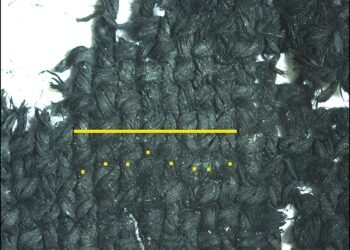

The study, published in the journal PLOS One, utilized a combination of spatial and microwear data to analyze 341 lithic artifacts. This approach allowed researchers to identify distinct activity zones within the structures, highlighting how different materials such as wood, bone, antler, plant, hide, meat, and fish were processed.

Dr. Jess Bates from the University of York’s Department of Archaeology explained, “We found that there were distinct areas for different types of activity. Messy tasks like butchery were conducted in designated spaces, separate from cleaner activities like crafting bone and wooden objects, tools, or jewelry. This was surprising given the mobile nature of hunter-gatherers, who would often travel to find food. Yet, they demonstrated a very organized approach to creating not just a house but a sense of home.”

The three structures analyzed were likely cone-shaped or domed and built using wood from felled trees, possibly covered with plant materials like reeds or animal hides. This construction style provided both shelter and a sense of permanence.

Dr. Bates noted: “This new work on these very early forms of houses suggests that these dwellings didn’t just serve a practical purpose in terms of shelter from the elements. Certain social norms of a home were observed that are not massively dissimilar to how we organize our homes today.”

Previous studies have shown that these early inhabitants kept their dwellings clean, with evidence of sweeping inside the structures. The new research expands on this by demonstrating a sophisticated understanding of spatial organization and task-specific zones within the homes. This level of domestic order reflects a shared group understanding among the hunter-gatherers of how to organize tasks and maintain their living spaces.

The microwear analysis, combined with Geographic Information System (GIS) technology, provided a detailed interpretation of how tools were used and how activities were spatially distributed across the structures. This method has proven crucial in uncovering the complexities of Mesolithic life at Star Carr.

Dr. Bates concluded, “In modern society, we are very attached to our homes both physically and emotionally, but in the deep past, communities were highly mobile. It is fascinating to see that despite this, there is still this concept of keeping an orderly home space. This study shows that micro-scale analysis can be a really exciting way of getting at the details of these homes and what these spaces meant to those who lived there.”

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.

I’m constantly being surprised by new discoveries and the revelations they provide on ancient humanity. Once a period recognisable by simple flint tools, we are now discovering that, at least for some communities, life had far more structure (including architecture) than previously thought.