Researchers have uncovered a prehistoric quicksand trap in Spain that ensnared large herbivores.

The Fuente Nueva 3 (FN3) archaeological site in Granada, southern Spain preserves some of the earliest evidence of human presence in Western Europe, dating back approximately 1.4 million years. Among the notable discoveries are carved stones, or lithic tools, and manuports, which are unmodified stones used for various purposes, including breaking bones to access marrow and as throwing weapons to deter predators.

The FN3 site also contains numerous fossils of large mammals, many of which exhibit marks from skinning, butchering, and marrow processing activities, indicative of early human tool use. Additionally, some bones bear tooth marks from scavenging carnivores.

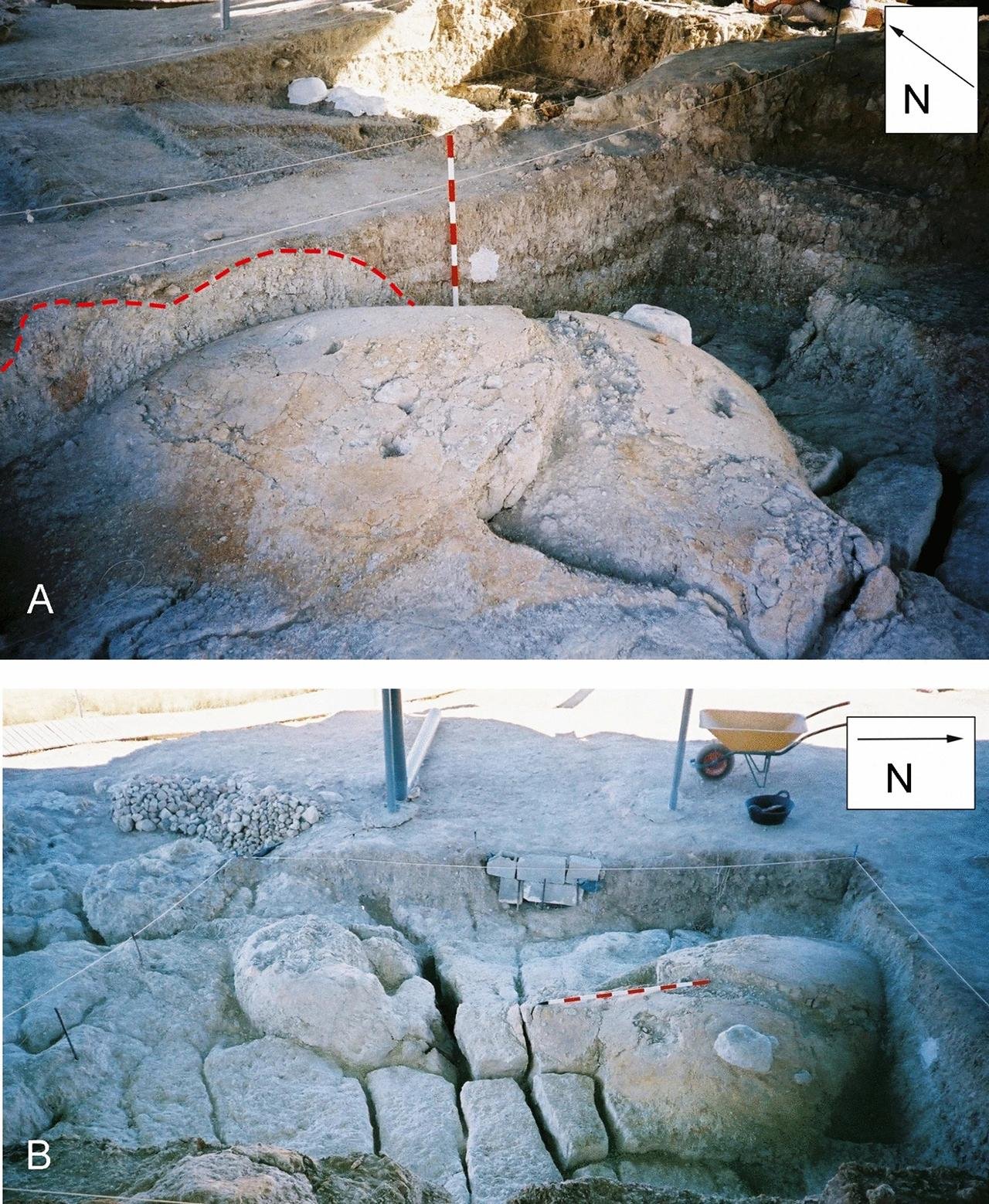

The study, led by a team of researchers from the University of Málaga (UMA), including Full Professor of Paleontology Paul Palmqvist and Professor of Stratigraphy and Paleontology María Patrocinio Espigares, analyzed the sedimentology of the FN3 site. They found that the site contains two distinct archaeological levels: a lower level (LAL) and an upper level (UAL).

The LAL shows a high density of manuports, suggesting intense hominin activity, while the UAL contains numerous remains of megaherbivores, particularly the extinct elephant species Mammuthus meridionalis. This level also preserves many hyena coprolites, indicating significant scavenger activity.

The researchers noted that the fine and very fine sands in the UAL, deposited near a prehistoric lake, likely functioned as quicksand. The substantial weight of megaherbivores would cause them to become trapped, attracting scavengers like hyenas and early humans. These predators fed on the trapped animals, leaving behind lithic tools and coprolites as evidence of their presence.

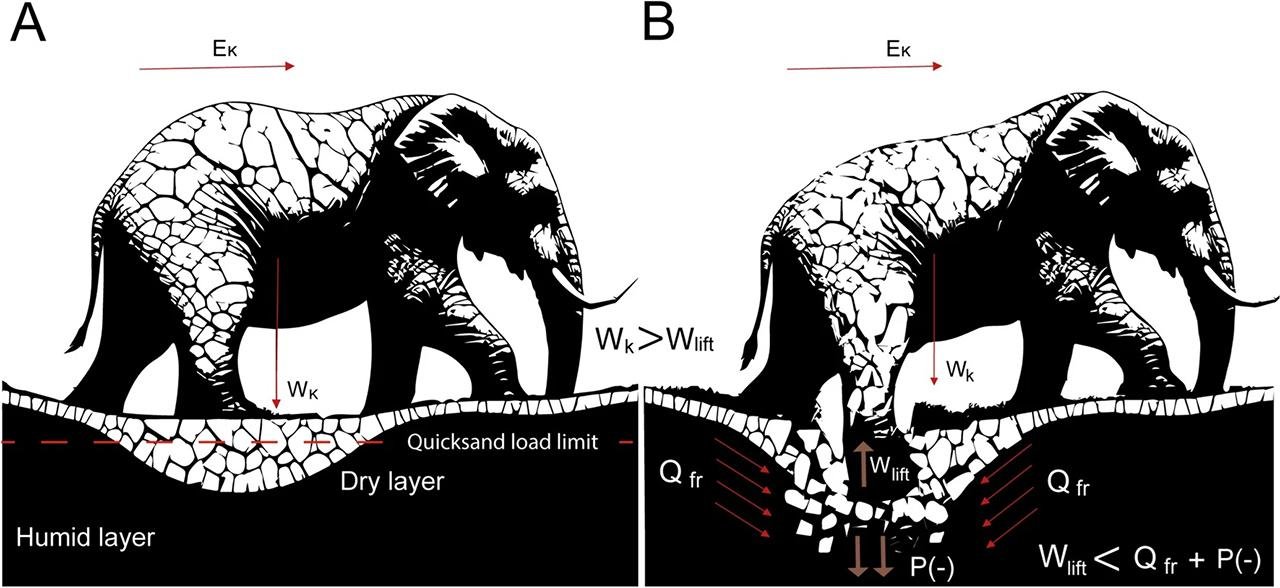

Quicksand can be a lethal trap for wildlife due to its unique properties. When an animal steps into quicksand, the sediment separates into a water-rich phase and a sand-rich phase, increasing viscosity and making escape difficult. “Quicksand can potentially be a deadly trap for wildlife,” the study’s authors wrote. “In such an environment, viscosity can reach such high levels that an animal may require a force up to three times its weight to free itself from the sediment.”

While megaherbivores like elephants were vulnerable to quicksand, smaller animals and scavengers, including hyenas and early humans, could navigate the surface without risk of sinking.

The researchers drew parallels between prehistoric quicksand traps and modern-day incidents where large mammals become mired in mud. For example, in Zimbabwe’s Mana Pools National Park during the 2019 dry season, a mother elephant and her calf became stuck in a muddy water hole. The calf was eventually eaten by hyenas, and the mother died from dehydration days later.

These findings shed light on early human subsistence strategies and their competition with hyenas for carrion. The study marks a significant milestone in understanding the behavior of early Europeans. “It is the first time a natural trap with these characteristics has been described in a fossil deposit of special interest to human evolution,” the UMA researchers stated.

The team plans to conduct further studies to differentiate the upper and lower archaeological levels in greater detail and to characterize other important sites in the Orce region, such as Barranco León, which also provides evidence of early human presence.