Scientists have unveiled a detailed account of the life and death of a baby boy who lived around 17,000 years ago in southern Italy during the Ice Age.

The child’s remains, discovered in 1998 in the Grotta delle Mura cave near Monopoli, Puglia, have provided a rare glimpse into the health and ancestry of ancient populations. A recent study, published in Nature Communications, reveals details about the boy’s physical traits, genetic heritage, and the challenges faced by him and his family.

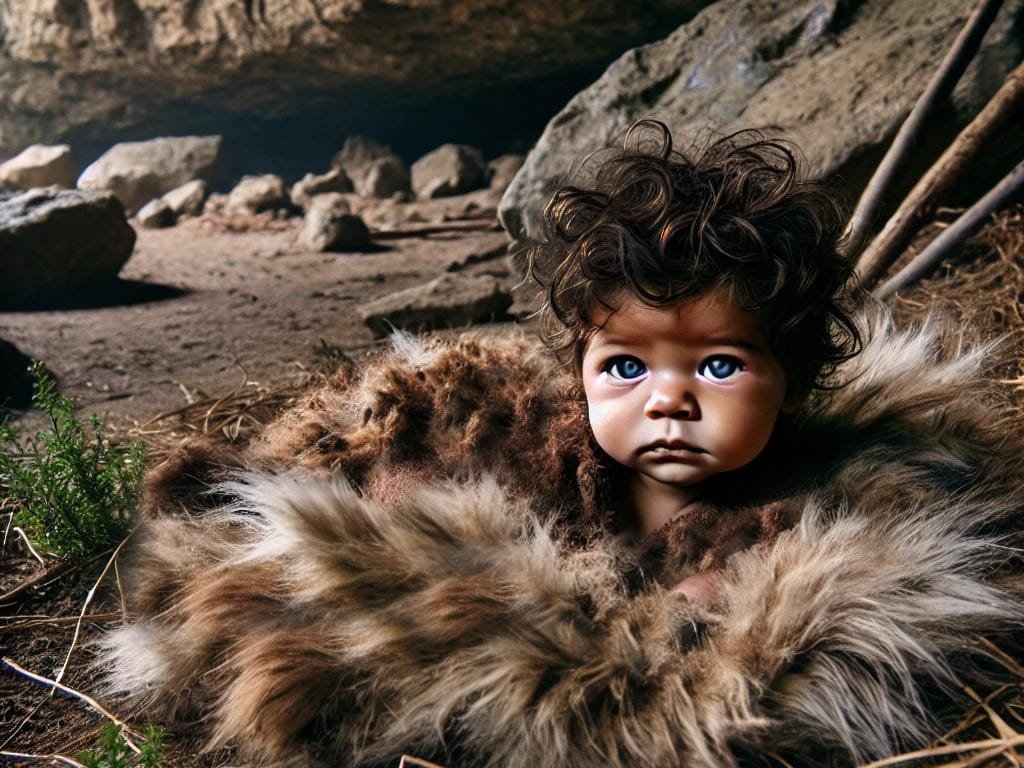

The child, believed to be around 16 months old at the time of his death, was found buried under two large rocks in the cave. The skeleton was largely intact, allowing researchers to perform a detailed analysis. DNA tests revealed that the boy likely had blue eyes, dark skin, and curly dark-brown hair. His remains also suggested a genetic predisposition to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a condition that thickens the heart muscles and likely contributed to his death, as reported by researchers Alessandra Modi from the University of Florence and Owen Alexander Higgins from the University of Bologna.

The DNA analysis also revealed that the boy was an ancestor of the Villabruna cluster, a group of post-Ice Age people who inhabited southern Europe. His genetic lineage offers new evidence that groups like the Villabruna were present in Italy before the Ice Age ended, confirming that these populations had already settled the region.

The child’s dental remains provided further insights into his life, including evidence of nine physiological stress events, likely stemming from his mother’s malnutrition during pregnancy. Strontium isotope analysis of his teeth indicated that his mother likely stayed in one area during her pregnancy, which may have been due to poor health.

One notable finding was that the child’s parents were likely cousins, as revealed by genetic testing. Although inbreeding was not common among most Paleolithic populations, it was more prevalent in small, isolated groups like those in southern Italy during the Ice Age. This, along with the child’s genetic heart condition, likely contributed to his premature death.

The boy’s burial was simple, with no grave goods accompanying his body. However, the discovery of his remains, the only grave found in the cave, has provided researchers with crucial information about the living conditions and challenges faced by ancient populations in the region.