Archaeological research at Manot Cave in Galilee, Israel, has unveiled extraordinary evidence of ritualistic gatherings dating back 35,000 years, marking the earliest such discovery on the Asian continent.

Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the findings highlight the cave’s dual role as a dwelling and a site for profound spiritual and social activities. The project, led by Israeli researchers and supported by international collaborators, provides critical insights into early modern human behavior and the interactions between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals.

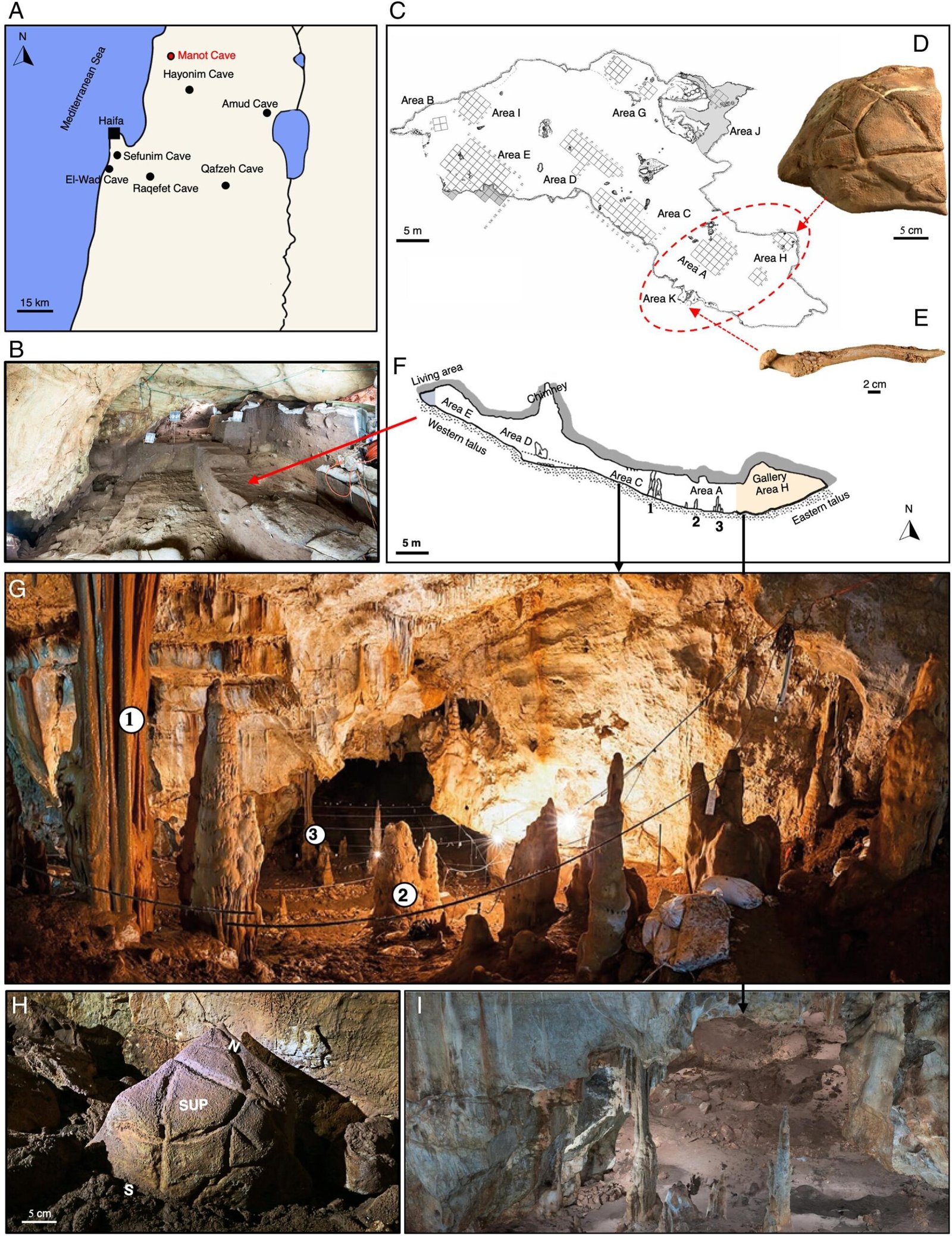

Manot Cave was discovered in 2008 by construction workers near Israel’s border with Lebanon. Researchers from Case Western Reserve University’s (CWRU) School of Dental Medicine joined the project in 2012, contributing expertise in identifying ancient human remains.

Dental students from CWRU leveraged their anatomical expertise to identify bone fragments. “Teeth, being harder than bones, are often the best-preserved elements in ancient skeletons,” explained Mark Hans, professor and chair of orthodontics at the dental school. “This makes dentistry an invaluable tool in anthropological studies.”

Recent studies reveal that the cave’s entrance housed daily activities, but its deepest chamber, located eight stories below, held significant ritualistic importance. This cavern, characterized by its acoustics conducive to large gatherings, contained an engraved rock with a turtle-shell design, dubbed the “turtle rock.” Deliberately placed in a niche, the carving’s symbolic placement suggests it served as a spiritual totem.

Traces of wood ash on nearby stalagmites suggest prehistoric humans used torches to light the chamber. This meticulous effort, combined with the site’s acoustics, underscores its significance as a gathering place.

The research brought together institutions such as the University of Haifa, Tel Aviv University, the University of Vienna, and the Leakey Foundation. Financial support came from organizations including the Dan David Foundation, the U.S.-Israel Binational Science Foundation, and the Irene Levi Sala CARE Archaeological Foundation. This collective effort has significantly advanced understanding of early human rituals and social structures.