Archaeologists working at Guatemala’s Tikal National Park have unearthed a lavishly painted altar that reveals new information about the past relationship between Tikal, an ancient Maya city, and the central Mexican metropolis of Teotihuacan. The altar, situated in a private complex mere steps from the heart of Tikal, has been characterized by scientists as a rare and revealing artifact that points to cultural exchange and a dramatic political upheaval that unfolded more than 1,600 years ago.

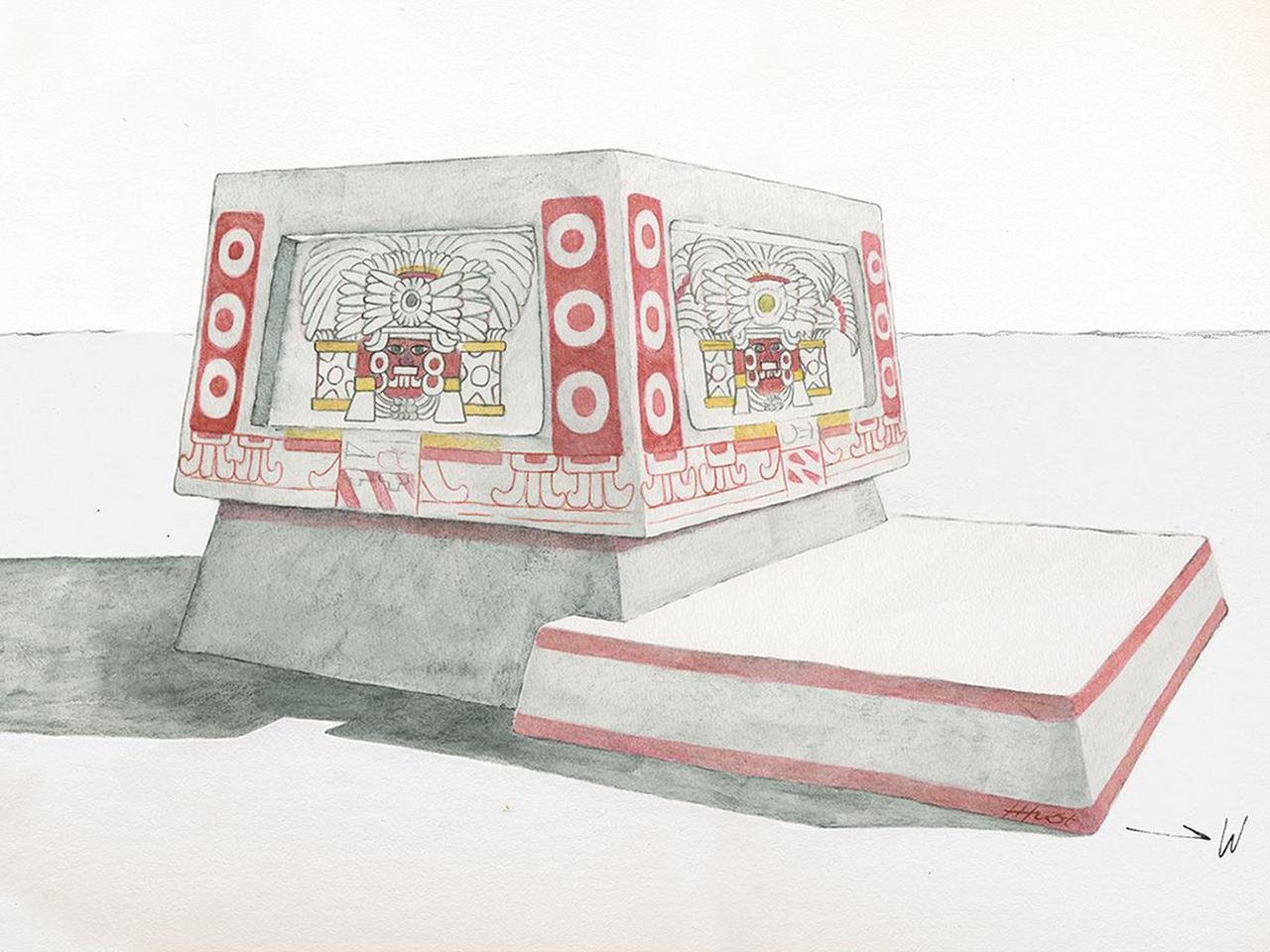

The altar, dating from the late 4th century CE, features intricate painted panels in yellow, black, and red, depicting a figure with almond-shaped eyes, a feather headdress, a nose bar, and a double earspool. The imagery is extremely close to central Mexican depictions of the “Storm God,” a god who was worshipped in Teotihuacan, some 630 miles northwest of Tikal.

The altar was likely constructed not by Maya hands but by a Teotihuacan-trained artisan, says a study published on April 8 in Antiquity and co-authored by researchers from Brown University and Guatemalan institutions. “It’s increasingly clear that this was an extraordinary period of turbulence at Tikal,” says Stephen Houston, a professor of anthropology and history of art and architecture at Brown University. “What the altar confirms is that wealthy leaders from Teotihuacan came to Tikal and created replicas of ritual facilities that would have existed in their home city.”

Excavation director Edwin Román, head of the South Tikal Archaeological Project, explained that the find demonstrates intense sociopolitical and cultural interaction between the two civilizations during the CE 300 to 500 period. Román added that the find verifies Tikal’s position as a cosmopolitan center at that time, hosting visitors and influences from distant regions.

The location of the altar, a two-yard-by-one-yard structure covered in limestone, had other features typical of Teotihuacan ritual practice as well. Human remains were present along with the altar, such as a child burial in a posture unusual for the Maya but common at Teotihuacan. A green obsidian dart point found with an adult buried nearby also matched Central Mexican weapon styles, testifying to the foreign presence.

Andrew Scherer, a Brown professor of archaeology and co-director of the project, stated that the altar was intentionally buried and the surrounding area was never reused. “The Maya regularly buried buildings and rebuilt on top of them,” Scherer said. “But here, they buried the altar and surrounding buildings and just left them, even though this would have been prime real estate centuries later. They treated it almost like a memorial or a radioactive zone. It probably speaks to the complicated feelings they had about Teotihuacan.”

The discovery of the altar also lends weight to long-standing speculation of a coup that reshaped Tikal’s leadership around CE 378. Decades of research show that Teotihuacan forces overthrew the local king and installed a puppet ruler in his stead, one who was aligned with their interests. Houston explained, “They removed the king and replaced him with a quisling, a puppet king who proved a useful local instrument to Teotihuacan.”

Additional proof of this theory is offered by earlier LiDAR (light detection and ranging) surveys taken by the Brown University team that revealed what appears to be a scaled-down replica of Teotihuacan’s central citadel buried near Tikal’s center. This structure, which had been mistakenly identified as natural hills, implies an extended and potentially permanent occupation or surveillance presence.

Despite the disruptive record of Teotihuacan’s intervention, Houston posited that the event might have paradoxically increased Tikal’s regional power in the long run. “There’s a kind of nostalgia about that time,” he said. “Even when they were in decline, they were still thinking about local politics in the context of that contact with central Mexico.”