Over 1,200 new archaeological sites were uncovered in Sudan’s Bayuda Desert by a Polish team of archaeologists, establishing the prehistoric and historic significance of the region once again. A six-year research mission by scholars from the University of Wrocław, the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology at the University of Warsaw, and the Archaeological Museum of Gdańsk has unearthed a trove of discoveries spanning from the Paleolithic period to the medieval period.

Among the most striking findings was a saline paleolake near Jebel El-Muwelha, which means “Salt Mountain,” at the heart of the Bayuda Desert. It was an ancient lake that served as a natron source, a rare mineral used in the past for mummification, as well as for the production of glass and ceramics.

The Bayuda Desert, which lies in central Sudan and is bordered by a bend of the Nile, remains one of the least explored areas in the country. While sporadic archaeological work began around the middle of the 20th century, systematic exploration only gained momentum in the 21st century. In the Polish-led National Science Centre (NCN) project Prehistoric Communities of the Bayuda Desert in Sudan – New Boundaries of the Kingdom of Kerma, researchers identified 448 new sites and re-examined 126 previously known sites. Excavations were conducted at 88 sites, of which 36 were cemeteries and 55 settlements.

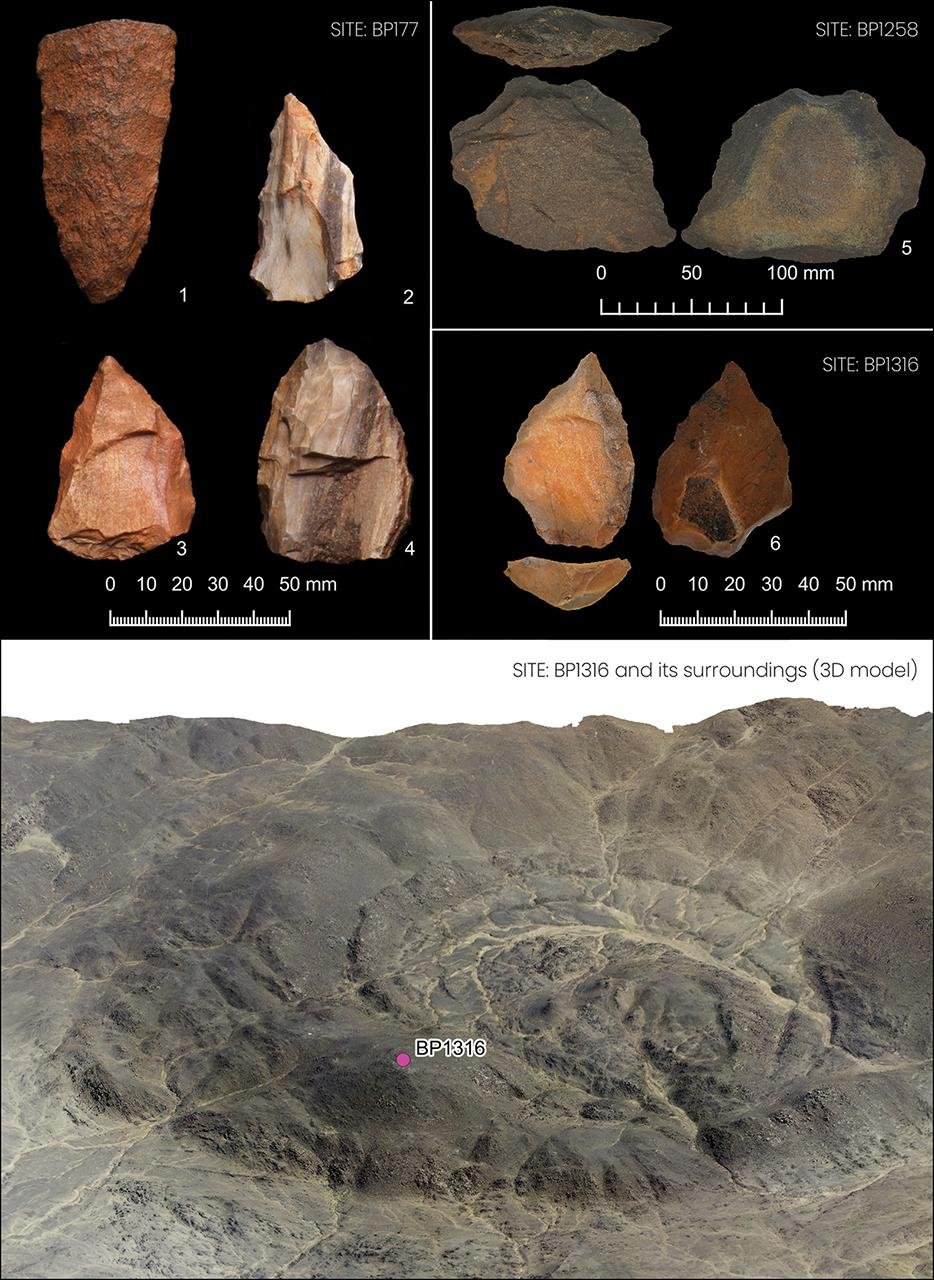

The discoveries span a broad range of history, including Oldowan stone tools that date between 2.6 and 1.7 million years ago and represent the world’s earliest known tool industry, through to medieval settlements and cemeteries. The earliest sites, discovered in the northwestern and southeastern parts of the desert, included Acheulean industry artifacts, renowned for large, bifacial hand axes and flakes.

Evidence of Middle Stone Age activity was also found. The Levallois technique, a sophisticated method for creating flakes that requires the careful preparation of stone cores, was found. This technique has been associated with early Homo sapiens. “Its use involved the need to perform many intermediate steps to shape the core in a way that allowed the removal of a single flake of the intended shape,” explained Prof. Paner. “This indicates the early presence of Homo sapiens in this part of Africa.”

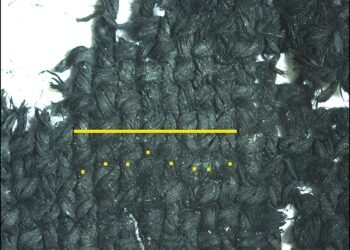

Among the discoveries related to the climate are the remains of savannah species and beetles discovered inside a clay vessel at a cemetery belonging to the historic Kerma culture (c. 2500–1500 BCE). The remains suggest a much more humid climate during the early centuries of the Kerma Kingdom.

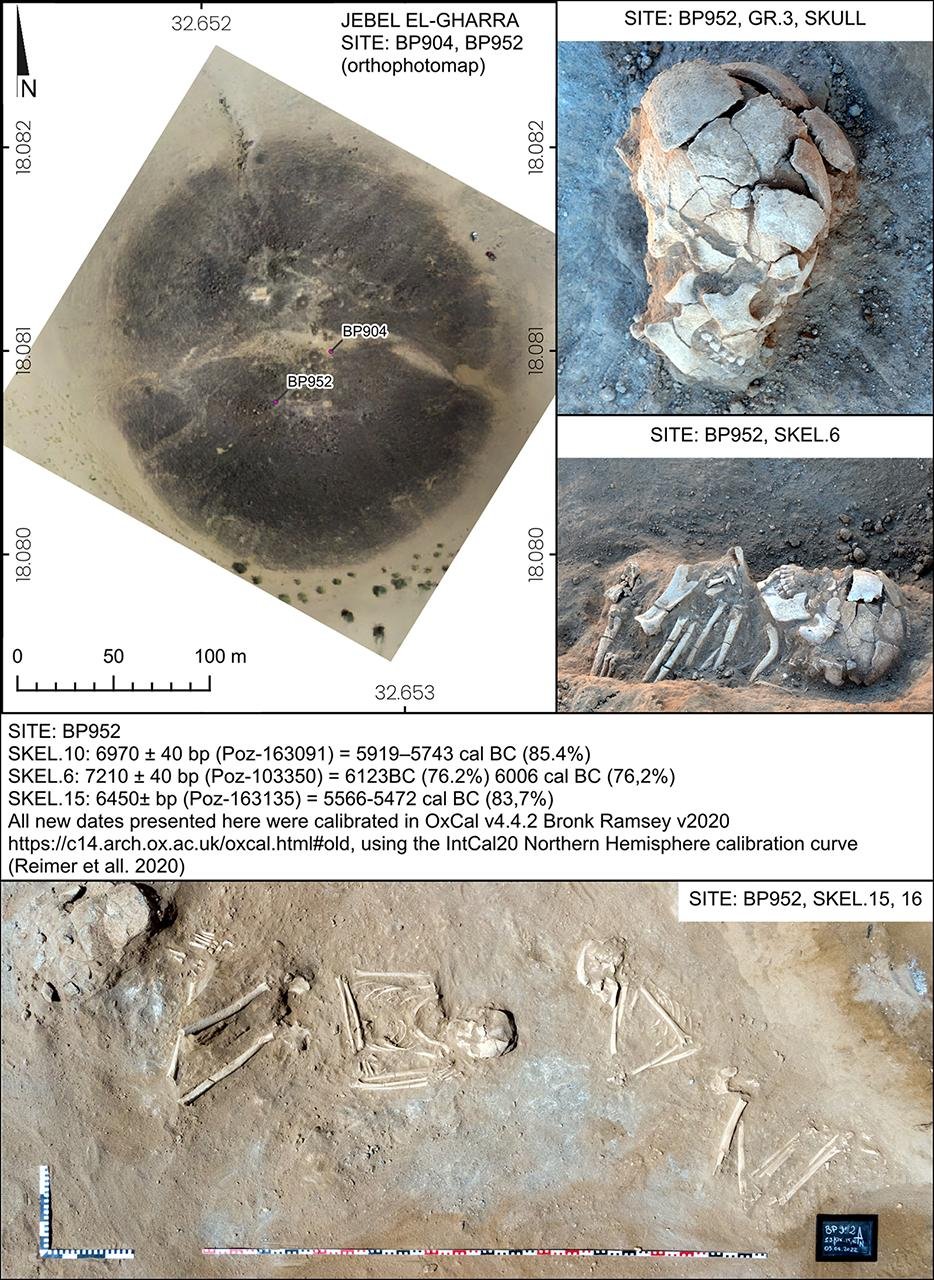

The researchers also uncovered the only known Mesolithic cemetery in the Bayuda Desert, on the Jebel El Gharra slope. There are at least 16 adult burials in multiple layers at the site, dated to the 7th–6th millennia BCE. The burial offerings included ostrich eggshell beads, shells, and a stone pendant.

Another significant site, dubbed the “Hunters’ Settlement,” lies at the foot of Jebel El-Fuel in the eastern desert. There, almost 300 fragments of animal bones, over 3,400 stone tools, and approximately 2,000 pieces of pottery were discovered, all dated to around 6000 BCE. All the bones were of wild animals, which implies that the site was likely used by hunter-gatherers.

The extensive findings were published in Antiquity.