No animal is as entangled in human history as the horse. The horse’s domestication allowed early humans to settle the vast Eurasian steppe; horses then made new forms of warfare, encouraged long-distance trade routes, and acquired deep cultural and religious significance. Horses eventually gave great power to empires in Iran, Afghanistan, China, India, and, much later, Russia.

No animal is as entangled in human history as the horse. The horse’s domestication allowed early humans to settle the vast Eurasian steppe; horses then made new forms of warfare, encouraged long-distance trade routes, and acquired deep cultural and religious significance. Horses eventually gave great power to empires in Iran, Afghanistan, China, India, and, much later, Russia.

by: David Chaffetz

Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

Publication date: July 15, 2025

Language: English

Hardcover: 448 pages

ISBN: 978-1-324-11033-0

Raiders, Rulers, and Traders: The Horse and the Rise of Empires by David Chaffetz presents a sweeping history of human civilization through the lens of this powerful ally. He explores how horses made rulers, raiders, and traders interchangeable and offers a fresh perspective on the “Silk Road,” suggesting it might be more aptly named the Horse Road. From ancient epics to the games of polo and Buzkashi, horses have symbolized authority, woven into the fabric of diverse cultures. Chaffetz, an astute observer of history, economics, and international relations, draws on fresh research in genetics and forensic archaeology to present a lively history of the great horse empires that shaped civilization.

Author

David Chaffetz is a regular contributor to the Asian Review of Books, a member of the Royal Society for Asian Affairs, and the author of A Journey through Afghanistan and Three Asian Divas. With over forty years of travel experience in Asia, he divides his time between Lisbon and Paris. A graduate of Harvard University, Chaffetz had the privilege of studying with two great scholars of Inner Asia, Richard Frye and Joseph Fletcher.

Reviews

The book received great reviews when it was published last year—it was selected as an Editor’s Choice by The New York Times and was reviewed in The Wall Street Journal, The Economist, The Financial Times, The New York Review of Books, and several other influential publications.

“A dog may be humanity’s best friend, but the horse is certainly the greatest ally. . . . From milking to marauding, David Chaffetz’s Raiders, Rulers, and Traders takes the reader on a well-paced ride through the history of this revolutionary and emotional alliance of human and animal.” — Jack Weatherford, New York Times best-selling author of Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World

“A fascinating, compelling, and scholarly history of horses, raiders, and rulers that brings the great horse-powered empires of Central Asia to life and places the horse at the center of world history where it belongs.” — Simon Sebag Montefiore, New York Times best-selling author of The World: A Family History of Humanity

“Vividly narrated … reads like an enthralling travel memoir…. Chaffetz’s account of how horses and landscapes shaped the distant past glimmers with myriad fascinating insights, seamlessly woven into a cohesive whole.” ― Deborah Hopkinson, BookPage, starred review

“Lively…. Chaffetz brings an authoritative tone to his complex tale, and he includes maps, illustrations, a glossary, and a particularly helpful timeline that runs from 20,000 BCE into the mid-20th century. The result is a consistently engaging and highly informative narrative. Chaffetz ably traces swathes of history across continents, underlining how horses made kingdoms and cultures.” ― Kirkus Reviews

Q&A with David Chaffetz, author of Raiders, Rulers, and Traders (by Pellien Public Relations)

1. How can understanding the role of horses in developing civilizations help us better understand the challenges we face today? Are there lessons for modern economies and states?

Everything depended on the horse. From day-to-day people’s livelihoods to emperors’ powerful cavalries, horses shaped the way people thought about government. Horses connected peoples of different cultures and allowed them to exchange ideas about religion, philosophy, and art. Let’s think about how dependent we are today on the Internet and how much would change if we no longer could use it. Both the horse and the Internet stopped being simply a tool, or a technology, and became a whole way of life.

2. You are best known as a scholar of Asian history – what compelled you to focus on the way horses shaped civilizations?

The great civilizations of Asia are pretty far away from one another, yet there are so many connections between them. They fought wars with one another. They adopted one another’s religions. They copied one another’s arts, and they learned one another’s languages. For example, China had a bureau, solely for the purpose of writing and receiving letters in Persian – for hundreds of years. What was the gearbox that connected these far flung countries? What brought them together in war or in peaceful trade? After many years of thinking about this, it dawned on me that horses played this role.

3. Why do you think the influence of the horse on building civilizations is so poorly known?

Because most histories focus on a single country, like China or India, and try to tell their stories from the inside out. But if you look at Asia as a whole, you see the interactions between these countries and the steppe, with its 10 million horses. Only then do you see that you can’t understand the history of China if you ignore the continuous dialogue between China and the steppe; China, the steppe, and India; China, the steppe, and Iran, and so on.

4. In the prologue, you share your experience riding in Afghanistan. Did this experience deepen your understanding of the relationship between horses and riders?

In 1976, I actually bought my own horse and set out on a ride through the Hindu Kush. This experience taught me what it is like to be completely dependent on your four-legged companion, a good perspective for studying how horses shaped human civilization.

5. In your research, did you find any particularly unique or surprising horse-related traditions that persist today?

It’s quite amazing how many ancient traditions persist. The tradition of the “riderless horse”— a horse with empty boots turned backwards in the stirrups in a funeral procession— as was done for John F. Kennedy, is a very ancient ritual to recognize the loss of a military leader. Horse-hair-topped banners, still common in Central Asia, go back to the time of horse (and human) sacrifices.

6. How do you think the relationship between humankind and horses will evolve in the coming centuries?

There is a new horse age coming, where humans will look to horses for all the aspects that have been squeezed out of modern life: beauty, companionship, unpredictability, vulnerability, danger. Horses are now being used more for therapy and for show than for utilitarian purposes. This is where they still shine.

7. This book spans thousands of years and countless wars, empire formations, and drastic changes to humanity. How did you balance that extreme expanse of time while telling the stories accurately?

The short answer is that I have been selective. A specialist in any one era or country will notice that I have omitted entire dynasties and centuries, because they did not advance the story. Early on, I decided to focus only on specific incidents or episodes that illustrate the importance of horses, and I made sure to research these topics thoroughly, using primary and secondary sources to ensure accuracy.

8. If we had hunted horses to extinction as we nearly did in ancient times, how do you think our society would look today?

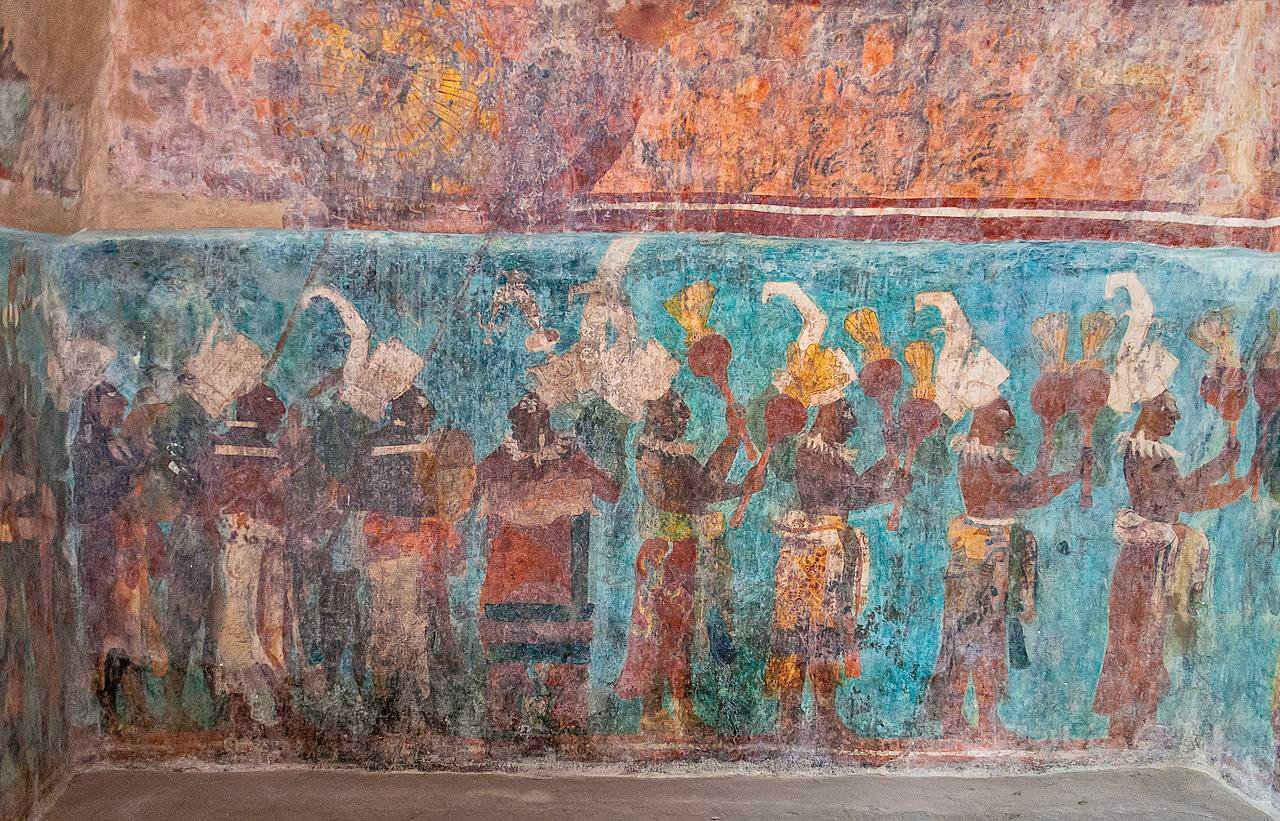

Eurasia would have evolved very much like the Americas and Africa south of the Sahara. In those places, the absence of a reliable means of transport and communication meant that isolated civilizations arose and flourished (think Zimbabwe or the Mayas) but then disappeared and left no heirs. Sea-faring peoples like the Malays or the Scandinavians would have had, relatively speaking, a much bigger impact on history because they would have been the only means of connecting different lands.

9. Your book mentions that captured foals were used as decoys to lure mares. Can you speak more about this early domestication and what it looked like?

It is common among hunters to keep a young animal in order to attract adult targets. Horses are just one instance of this. It took much longer to make the transition from hunting to milking horses than it did for sheep, goats, or cattle, but the process would have been absolutely the same. Over time these captured foals would grow up to become mares. They would have been comfortable enough living among humans to allow us to milk them, and lo-and-behold, the horse becomes the most valuable addition to our livestock. Keep in mind that in those days, horses gave as much milk as cattle.

10. Horses made the long-distance formation of the “Silk Road” possible, bringing together cultures from far reaches of the globe, particularly Central Asia. How did this impact the relationships between societies, and what were some of the most crucial developments?

For China, especially, it opened their eyes to the existence of sophisticated cultures far beyond their immediate neighbors, whom they viewed as pretty primitive. On the back of the horse trade, many foreigners came to China, bringing new religions, including Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and Buddhism, new technologies, fashions, and even music and songs. Later the horse dealers themselves —the Turks and then the Mongols—took charge and ruled empires stretching from China to Rome. Finally, the big empires, India, China and Russia, around the steppe decided to conquer the steppe and bring their frontiers adjacent to one another.

11. How did horses change military strategy and the nature of combat?

Remember that chariots preceded cavalry. The chariot-riding warrior, think Achilles and Hector, appears in the Iliad. They fight in single combat. Then, as empires grow in size, they field massed chariots the way we field tanks today. The difficulty of maintaining a large chariot force opens the door to light cavalry, armed with bows and arrows. Later, as horses get stronger, heavy armoured warriors fight on horseback with lances, maces, lassos, and swords. Finally, as equestrian skills are really developed, the cavalry trooper armed with a sabre emerges. The role of cavalry is always to find the enemy, to harass him, to threaten his flanks, and occasionally, when the time is ripe, to put him to flight with an impressive and irresistible charge.

12. Ghengis Khan’s legacy as a conqueror and strategist remains one of the most significant in history. Can you talk about how he revolutionized steppe statecraft, particularly in his use of horses, to achieve his dominance?

Genghis Khan exploited steppe horsepower with unprecedented rigor. He planned and executed massive movements of cavalry over vast distances, based on accurate intelligence from his spies, as to how much pasture his divisions required for their horses. He deployed his forces over huge fronts, to take advantage of available pasture, but then concentrated his forces at the chosen moment and location, to overwhelm his surprised enemies. This rigorous approach to campaigning made him and his Mongols unbeatable.

13.Readers might be surprised by the outsized economic impact of horses – how did the cost of maintaining warhorses influence the economies of empires such as the Mongols or the Persians?

In agricultural societies, the trade-off between pastureland and farmland was often a costly one. The great empires had to set aside some amount of land for their horses to graze, which meant losing the land tax that would otherwise have been paid by farmers. They also had new expenses to cover, like employing grooms, vets, and trainers. In locations where horses could not graze outside, either because it was too cold, too wet, or too hot, they had to be stabled and fed fodder, at great expense. We can imagine that maintaining the cavalry of a great empire easily consumed half of the annual revenue of the empire.

14. Did the horse trade create economic dependencies between nomadic and agrarian societies?

They depended on one another. Remember that the animal population would normally increase constantly. Nomadic societies wanted to sell excess horses, and agrarian societies needed horses for defense, for transport, and for communications. The problem was, what could the agrarians sell the nomads in exchange for the horses? Originally, the Chinese traded costly presents for the horses. As the trade got bigger, the Chinese paid in raw silk, and still later, in bricks of tea. India developed a number of industrial products, especially cottons, that they sold for silver which was then used to buy horses.

15. You write about the final days of our reliance on horses – as railroads and automobiles took over – what are the lessons from this technological transformation?

It’s striking how fast technological transformations happen. My maternal grandfather and his father-in-law opened a horse farm operation near Redhook, NY, in 1912. This was very bad timing because the horse disappeared from the streets of NY just about then. We often talk about the fate of the buggy whip manufacturers, but technology transitions are more pervasive than that. Stables, carriage houses, blacksmiths, vets, knackers, and all kinds of trades disappeared. We are living through something similar right now with the advent of AI. What is interesting is that in the optimism of the Ragtime era, no one worried about losing these old trades, unlike the angst we are feeling now with AI and its impact on entire industries and job roles.