New research by Cambridge criminologist Professor Manuel Eisner has revealed the horrific murder of a priest nearly 700 years ago, uncovering a complex web of betrayal, noble defiance, and revenge that unfolded at the heart of medieval London. The killing of John Forde in 1337 is among the hundreds of killings that have been documented by the Medieval Murder Maps project, which examines patterns of violent death in 14th-century English cities such as London, Oxford, and York.

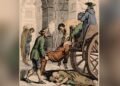

John Forde was a clergyman who had served as rector at Okeford Fitzpaine before being killed in what appears to have been a planned and symbolic assassination, according to Eisner’s research. The murder took place in Westcheap, a bustling market district and well-known hotspot for homicides, as crowds moved outside St. Paul’s Cathedral in the evening of May 3, 1337. Forde was first approached by a priest, Hasculph Neville, who engaged him in friendly conversation and allowed four men to assault him. Hugh Lovell, a brother of noblewoman Ela Fitzpayne, slit Forde’s throat with a 12-inch dagger. Two servants from the Fitzpayne household, Hugh Colne and John Strong, stabbed him in the belly.

Eisner’s findings, based on archival letters and coroner’s rolls, suggest the murder was premeditated by Ela Fitzpayne, a noble who had a past relationship with Forde. A letter from Archbishop Simon Mepham in 1332 denounced Ela for multiple adulterous affairs, including one with Forde, and imposed harsh public penance, including walking barefoot across Salisbury Cathedral with a wax candle. Despite these punishments, Ela appears to have refused compliance and even went into hiding. Her relationship with Forde came to an end, especially after speculation that Forde may have informed the Archbishop about her conduct.

Adding to the legend, a 1322 royal indictment revealed that Ela, her husband Sir Robert Fitzpayne, and John Forde participated in a raid on a Benedictine priory linked to a French abbey. The group is said to have stolen livestock and damaged church property—a threatening act when English-French relations were growing tense.

Professor Eisner argues that Forde’s murder was not just personal revenge but also a message: “We are looking at a murder commissioned by a leading figure of the English aristocracy… a brutal show of strength.” He added that the fact that it happened in public—carried out in daylight and in an open area—was similar to political murders in modern authoritarian regimes.”

The Medieval Murder Maps project situates Forde’s case within the broader context of urban violence in medieval times. Homicides in 14th-century cities tended to occur in central, denser areas like markets and church squares, particularly on weekends and evenings, when guild, apprentice, or rival faction tensions would be likely to rise. In contrast to modern cities, homicide was not highly correlated with impoverished neighborhoods, suggesting that violence was more likely to be the result of social friction than deprivation.

Only one of Forde’s killers, Hugh Colne, was ever charged—five years later, in 1342. The others seemingly evaded justice, due to a justice system influenced by class and connections. “Despite naming the killers and clear knowledge of the instigator, when it comes to pursuing the perpetrators, the jury turned a blind eye,” said Eisner.

Ultimately, John Forde’s case is an example of how violence, space, and social power converged in urban medieval cities. It also serves to show the role of humiliation as a driver of revenge. “Humiliation creates emotions of anger and shame,” said Eisner, “and soon after, this can harden into a desire for violence.”