A minor genetic difference in one of the enzymes may have helped separate modern humans from Neanderthals and Denisovans, our closest extinct relatives, and may have even contributed to the fact that Homo sapiens thrived while the others became extinct. These are the findings of a new study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), led by researchers at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) in Japan and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany.

The object of the study is the adenylosuccinate lyase (ADSL) enzyme, a protein that is centrally involved in purine metabolism — a biochemical pathway crucial for producing DNA, RNA, and energy in cells. Although the human and Neanderthal versions of ADSL differ by just a single amino acid out of 484, this minor change appears to have had significant effects on brain activity and possibly behavior.

“Through our study, we have gained clues into the functional consequences of some of the molecular changes that set modern humans apart from our ancestors,” said Dr. Xiangchun Ju, a postdoctoral researcher at OIST and first author of the paper, in a statement. The mutation at position 429 substitutes valine for alanine, a difference absent in Neanderthals and Denisovans but present in nearly all living humans.

Earlier studies had shown that this change made the human version of ADSL less stable than its Neanderthal counterpart, causing it to break down faster. In the new study, the scientists tested its effect by introducing the human version into genetically modified mice. The researchers noticed higher levels of ADSL’s substrates, particularly in the brain, which suggested the enzyme was less active. Surprisingly, this reduction seemed to have behavioral effects.

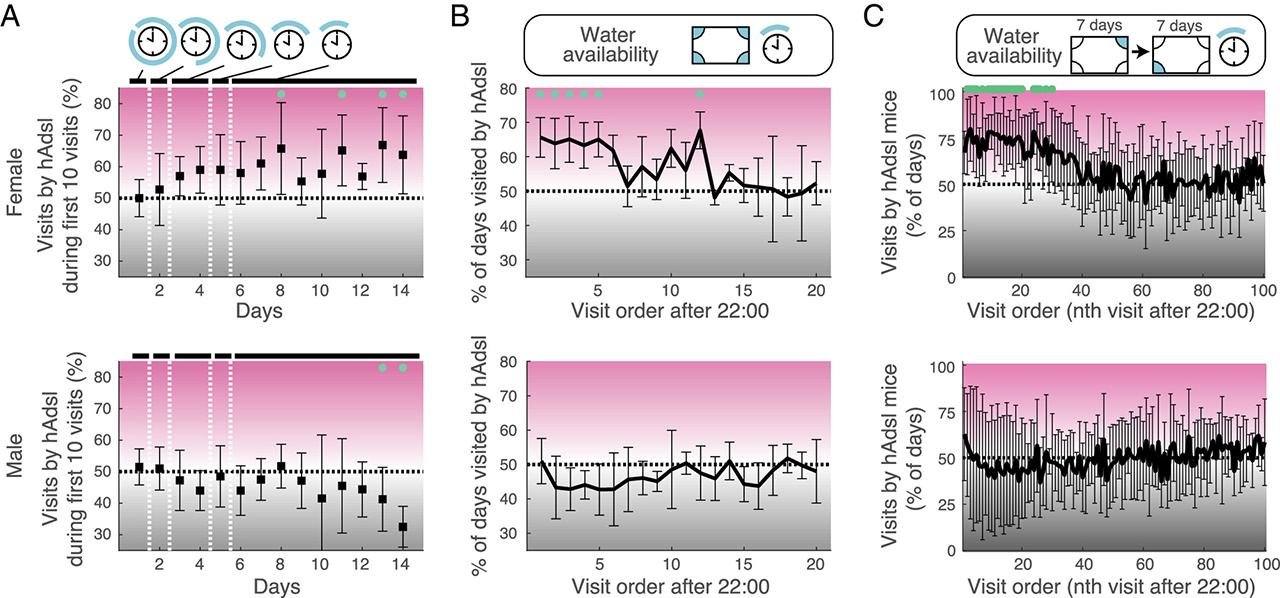

In experiments where mice had to learn to connect visual or sound cues with access to water, female mice carrying the human-like ADSL variant learned faster than their littermates. They were also quicker to access water when they were thirsty, showing a greater ability to adapt or compete for scarce resources. “It’s too early to translate these findings directly to humans, as the neural circuits of mice are vastly different,” cautioned Ju. “But the substitution might have given us some evolutionary advantage in particular tasks relative to ancestral humans.”

The team also discovered other genetic changes within a non-coding region of the ADSL gene, found in about 97% of modern humans. These variants reduced the enzyme’s activity by lowering its RNA expression, primarily in the brain. “This enzyme underwent two separate rounds of selection that reduced its activity – first through a change to the protein’s stability and second by lowering its expression,” said Dr. Shin-Yu Lee at the OIST in the statement. “Evidently, there’s an evolutionary pressure to lower the activity of the enzyme enough to provide the effects that we saw in mice, while keeping it active enough to avoid ADSL deficiency disorder.”

The behavioral effect, though, was only observed in female mice. “It’s unclear why only female mice seemed to gain a competitive advantage,” said Professor Izumi Fukunaga of OIST’s Sensory and Behavioral Neuroscience Unit. “Accessing water involves many brain processes — from sensory learning to motor planning and social interaction. More studies are needed to understand the role of ADSL.”

For Svante Pääbo, the Nobel Laureate and director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, and co-author of this study, the study is a pointer to how small molecular changes may have shaped our species. “There are a small number of enzymes that were affected by evolutionary changes in the ancestors of modern humans. ADSL is one of them,” he told OIST. “We are beginning to understand the effects of some of these changes, and thus piece together how our metabolism has changed over the past half million years of our evolution.”

While the work can’t fully explain why Neanderthals and Denisovans became extinct, it presents intriguing evidence that slight biochemical distinctions may have given Homo sapiens a cognitive edge. These advantages — in problem-solving, adaptability, or competition — may have been decisive for survival as climates shifted and resources decreased.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.

One issue I have with so much science reporting for us general public is illustrated here. Research reveals a genetic change which, when introduced into mice, seems to enable female mice to find water more quickly in an experiment, and the headline extrapolates this to a possible explanation of why Homo sapiens survived and other human species became extinct. Quite a leap in my opinion. At least the scientists pointed out this is an extrapolation.

As mentioned above, this is a science-based website. Since it has a broad audience, some topics may seem simplified or even exaggerated to non-academic readers. However, for us archaeologists, such experiments are quite clear and understandable, as laboratory models and animals with genetic similarities to humans are routinely used in diverse studies with different goals.

Surely at the time of the neanderthals hom.sap.sapientis didn’t look like a contemporary white European — an Australian or Indonesian aboriginal would have been a better choice for your graphic.

“Recent Neuroscience research has revealed a genetic difference between our subspecies and Neanderthals. In 2022, Pinson et al. published their findings about a single amino acid change in H. sapiens sapiens that differs from other early human subspecies, including the Neanderthals and Denisovans.22

The protein created from this gene (TKTL1) is involved in stimulating new neuron production in specific brain regions. In laboratory testing, the team was able to show that the mutated version shared by all modern humans (hTKTL1) caused greater neurogenesis in frontal higher-layer neocortical regions of the brain, as compared to the version of the protein shared by archaic humans [sic such as Neanderthals] and apes (aTKTL1).” – Once in a Species by Jesse Myers. (Comment sections can dislike links, so please just search: Once in a Species by Jesse Myers.

All interested in this topic will enjoy Mr Myers’ paper. He posits that the mutation caused Homo Sapien Sapiens to develop new brain functions that led to greater more abstract thought and attraction to scarcity, which in turn led to beaded shell jewelry, which as a proto-money led to enhanced cooperation between larger and larger groups of Homo Sapien Sapiens who were then able to develop advantageous population densities which out-competed and/or subsumed Neanderthal groups.

Yes. Most homo saps are not blue-eyed, or even “white”; that was a later variation. So I am always doubtful of exemplars that look like someone I know. Even the supposed Neanderthal depicted here reminds me of someone I once knew. Given how little anthropology can inform such depictions, and how much the artist has to fill in (usually from his/her own background)

Hypotheses is just that— hypotheses. Something to do further work on. Keep working.