The faces of centuries-old Colombian Andean mummies have been digitally reconstructed for the first time, providing a remarkable insight into pre-Columbian South America’s funerary traditions. The project, led by Liverpool John Moores University’s Face Lab in collaboration with Colombian institutions, was revealed this summer at the XI World Congress on Mummy Studies in Cusco, Peru.

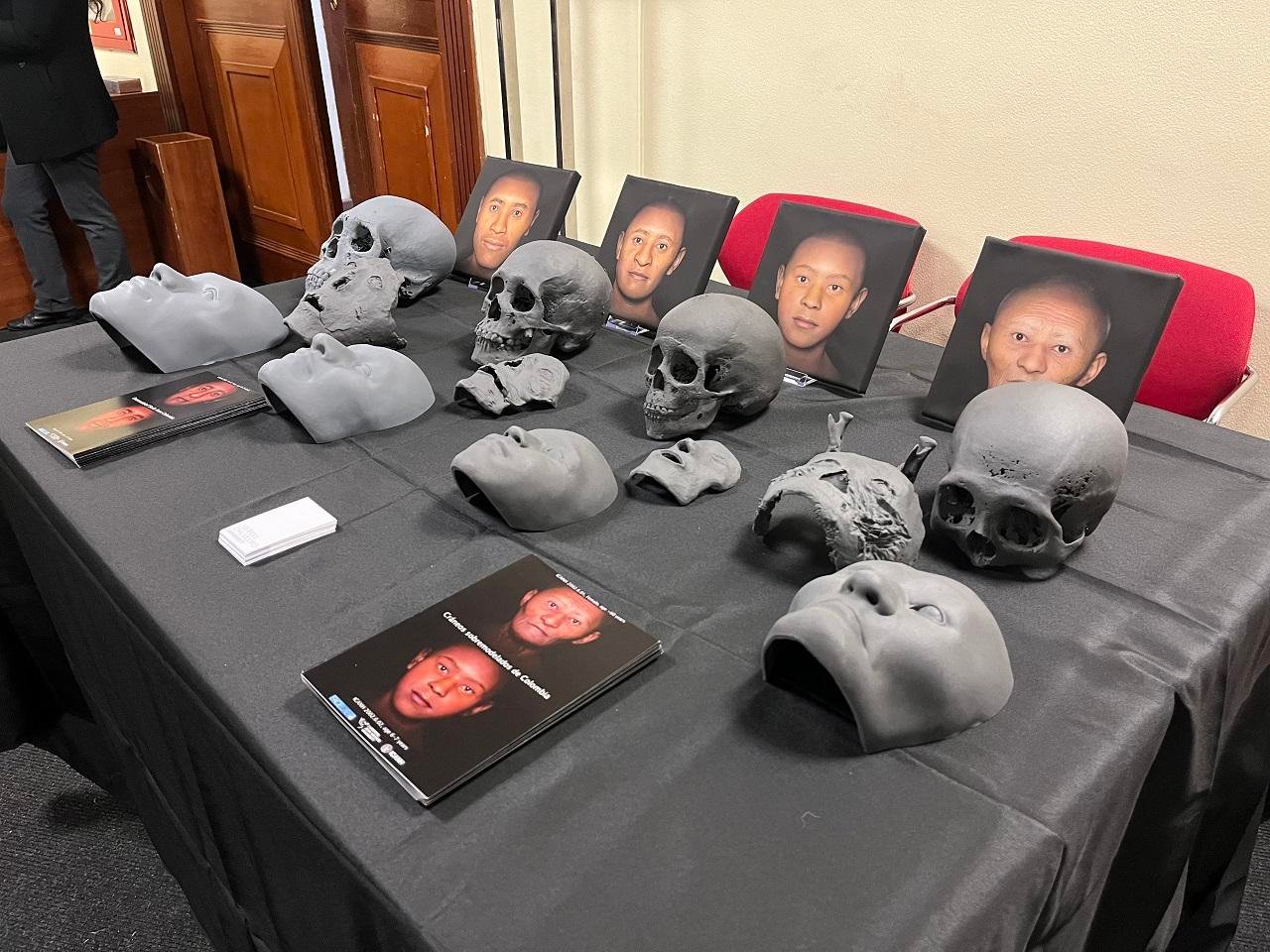

The mummies, dating between the 13th and 18th centuries, were individuals from pre-Hispanic groups in the Eastern Cordillera of the Andes. They were buried with a carefully crafted mask, which was modeled directly onto the skull, wrapping over the face and jaw. While in some South American cultures the use of death masks was common, these four are unique in Colombia and are preserved in the Colombian Institute of Anthropology and History collection.

The individuals included a child who was between six and seven years old, a woman in her 60s, and two young men. Their funerary masks were created from resin, clay, wax, and maize, which were frequently enhanced with beads or ornamental additions. Although damaged—missing noses and broken lower sections—the craftsmanship is still impressive. In some cases, the application of the masks was so exact that the mummified bodies were nearly lifelike.

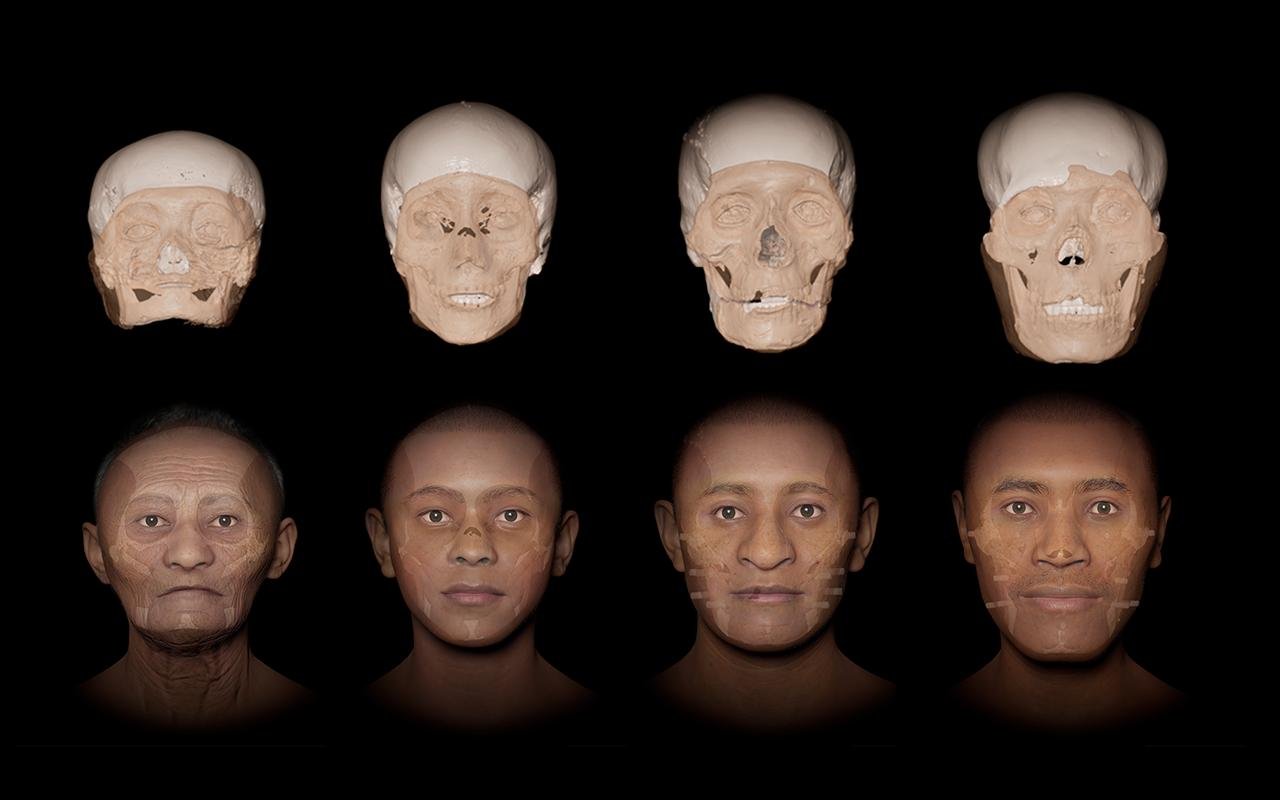

Sadly, looting of the original sites destroyed much of the archaeological context. With limited information about the individuals, researchers turned to digital techniques to learn more. The researchers created 3D virtual images of the skulls beneath the masks by using CT scans. These were then “unmasked” digitally, allowing anatomical analysis.

The reconstruction process combined forensic techniques with artistic interpretation. Researchers layered muscles, soft tissue, and fat onto the 3D skull models and used tissue depth data of modern adults in Colombia to guide proportions. As these do not exist for Colombian children or elderly women, the researchers adjusted features such as fat distribution and muscle shape to model what each would have looked like. The nose was determined through exact measurements of the nasal bones, and skin, hair, and eye color were based on what would have been typical for the region.

The later stages of the project involved meticulous digital sculpting to add texture—eyelashes, pores, wrinkles, freckles—to the reconstructed faces. Unlike stylized masks, the reconstructions present the people with neutral expressions, providing a more realistic view of how they may have appeared in life.

Beyond the technical achievement, the reconstructions are significant on a cultural level. The presence of decorated masks, sometimes incorporating gold or other valuable materials, reflects the complex beliefs and artistry of the communities that created them. The funerary practices signify not only a spiritual dimension but also technological progress in the management of diverse materials.

At Face Lab, established in 2015 as a pioneering hub of craniofacial research, the project demonstrates the power of bringing together science, technology, and heritage studies. While Face Lab often assists law enforcement in forensic identification, its heritage endeavors have helped museums and scholars reconceptualize the human past.

The unveiling of these digital reconstructions marks the first time the Colombian mummies’ faces have been revealed to the public. By virtually removing the funerary masks, scholars have restored individuality to people who lived more than five centuries ago, ensuring their cultural legacy continues to be recognized.

The unveiling of the virtual reconstructions marks the first time that the Colombian mummies’ faces have been revealed. By digitally removing the funerary masks, scientists have restored individuality to people who lived more than five centuries ago, ensuring that their cultural legacy is still remembered.

More information: Liverpool John Moores University / Face Lab

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.