Researchers working with the Central Mediterranean Penal Heritage Project (CMPHP) have used advanced remote-sensing methods to document the rare traces of daily life inside the former castle prison of Noto Antica in southeastern Sicily. Their work focuses on a set of carved gameboards and detailed engravings of galleys, which provide new insight into the ways inmates confronted the hardships of confinement in the Early Modern period.

Noto Antica sits on a plateau that was continuously inhabited from the early first millennium BC until its destruction in the 1693 earthquake. Today, the site is an archaeological park and retains the ruins of a medieval fortress, which once served as the town’s prison. Graffiti from the building has long been familiar to local visitors, but the CMPHP digital documentation provides the first systematic record of the carvings. Initiated in 2023, the CMPHP aims to establish a comparative dataset for sites of imprisonment across the central Mediterranean, spanning the fifteenth to early twentieth centuries.

To create a complete digital record of the interior of the prison, researchers used digital photogrammetry, capturing 747 high-resolution images and processing them in Agisoft Metashape. The resulting 3D model was transferred into Blender, where lighting conditions were digitally altered to enhance surface visibility. Individual frames were then exported and traced in GIMP to create the first detailed drawings of the graffiti.

Preliminary analysis has identified seven nautical engravings, five rectangular carvings interpreted as gameboards, and one carved head. The fact that the same rectangular motifs appear multiple times on horizontal surfaces strongly suggests that they were used as gameboards for a strategy game known as Nine Men’s Morris, which has been documented across Europe and the Mediterranean for hundreds of years. Their presence indicates that prisoners were allowed to pass time through play, an activity that, while not an act of overt resistance, offered a form of psychological opposition to the dehumanizing conditions of captivity. The number of gameboards further suggests that the cell, four square meters in size, would have held ten or more detainees.

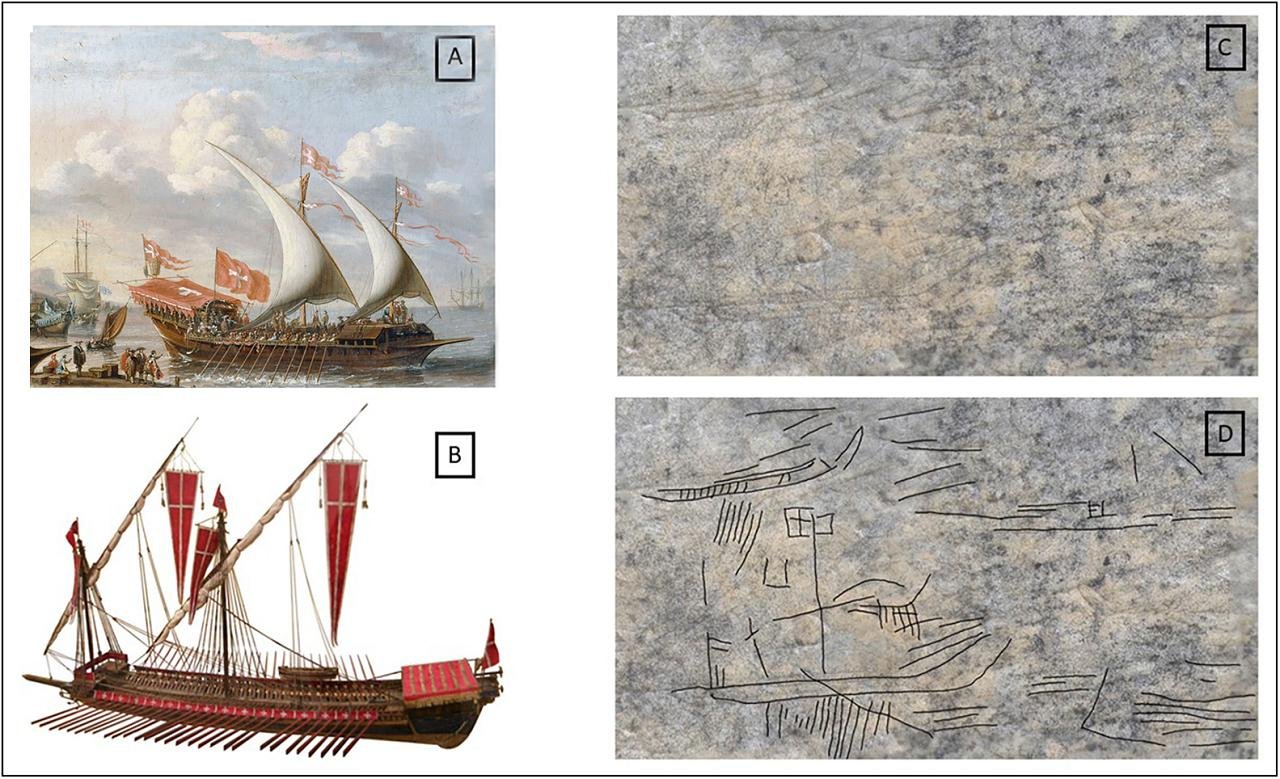

The ship carvings were studied with reference to the Malta Ship Graffiti Project. Three vessels display features characteristic of Mediterranean galleys, including low hulls, lateen sails, and lines representing banks of oars. Two fly flags bearing the cross of the Order of St John. The Knights of Malta, who had been established as rulers of the archipelago in 1530, depended heavily on galley fleets, each requiring around 280 rowers.

In the region, the labor force for these vessels was drawn from enslaved people, criminals sentenced to forced rowing, and debtors—populations numbering some 20,000 even during peaceful periods. The depiction of galleys in the prison may thus reflect the prisoners’ fears of such punishment or their knowledge of maritime warfare and privateering in the central Mediterranean.

The CMPHP’s findings emphasize the importance of digital recording for fragile heritage and shed light on the lived experiences of early modern prisoners. The carvings from Noto Antica reflect moments of storytelling, coping, and memory-making in a system where confinement usually preceded more severe forms of discipline.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.