Until recently, Aguada Fénix had lain hidden beneath the fields and forests of southeastern Mexico for millennia. The vast earthen platform, built more than 3,000 years ago, represents the oldest and largest monumental structure known in the Maya region, placing it almost a millennium before cities such as Tikal and Teotihuacán in age and rivaling both in scale.

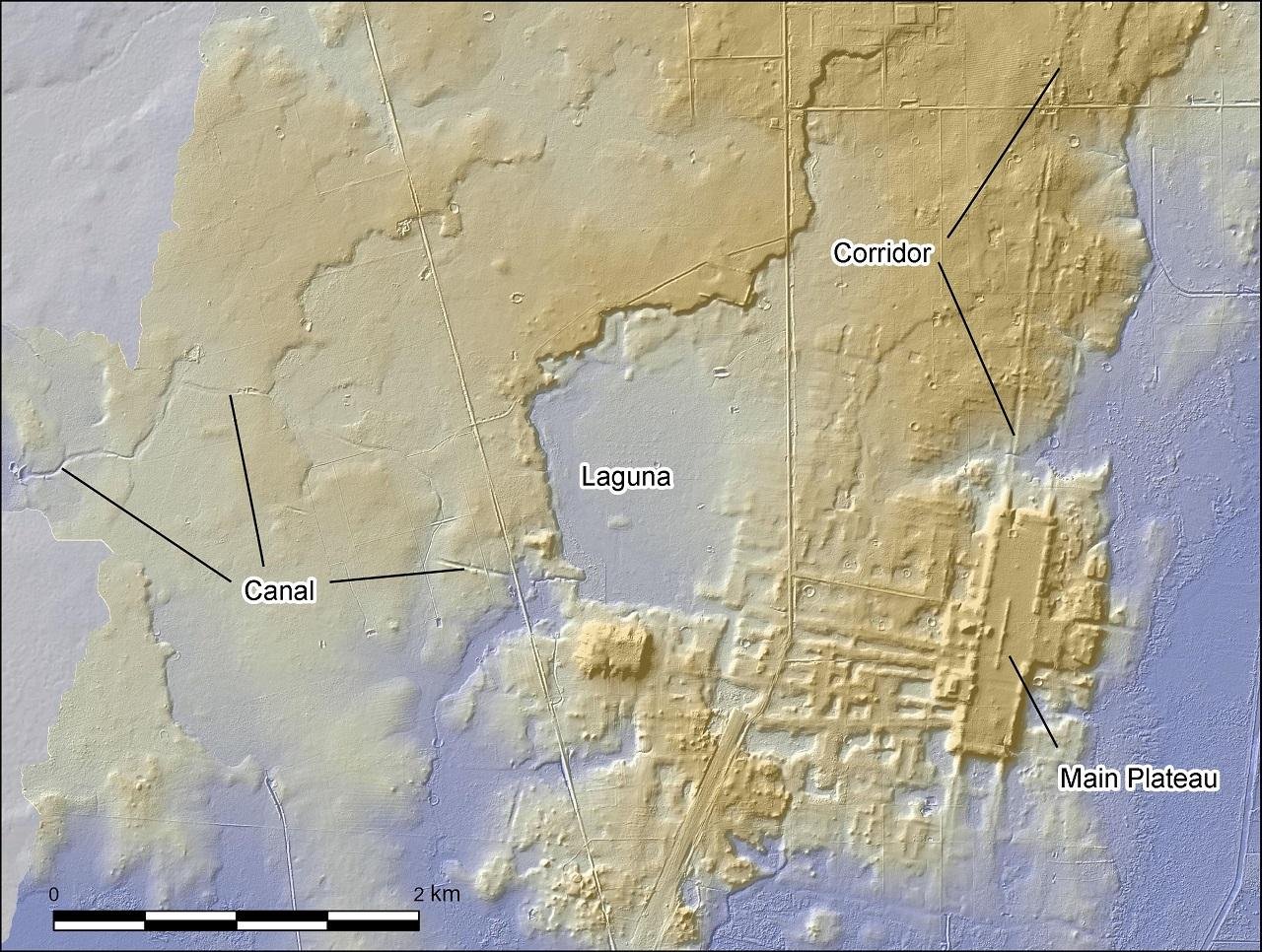

Discovered in 2020 by a University of Arizona team led by Takeshi Inomata and Daniela Triadan using LiDAR technology, the site stretches nearly a mile long, a quarter of a mile wide, and rises up to 50 feet high. The LiDAR scans also revealed hundreds of smaller but related sites scattered across Tabasco’s landscape, suggesting a thriving cultural network at the dawn of Maya civilization.

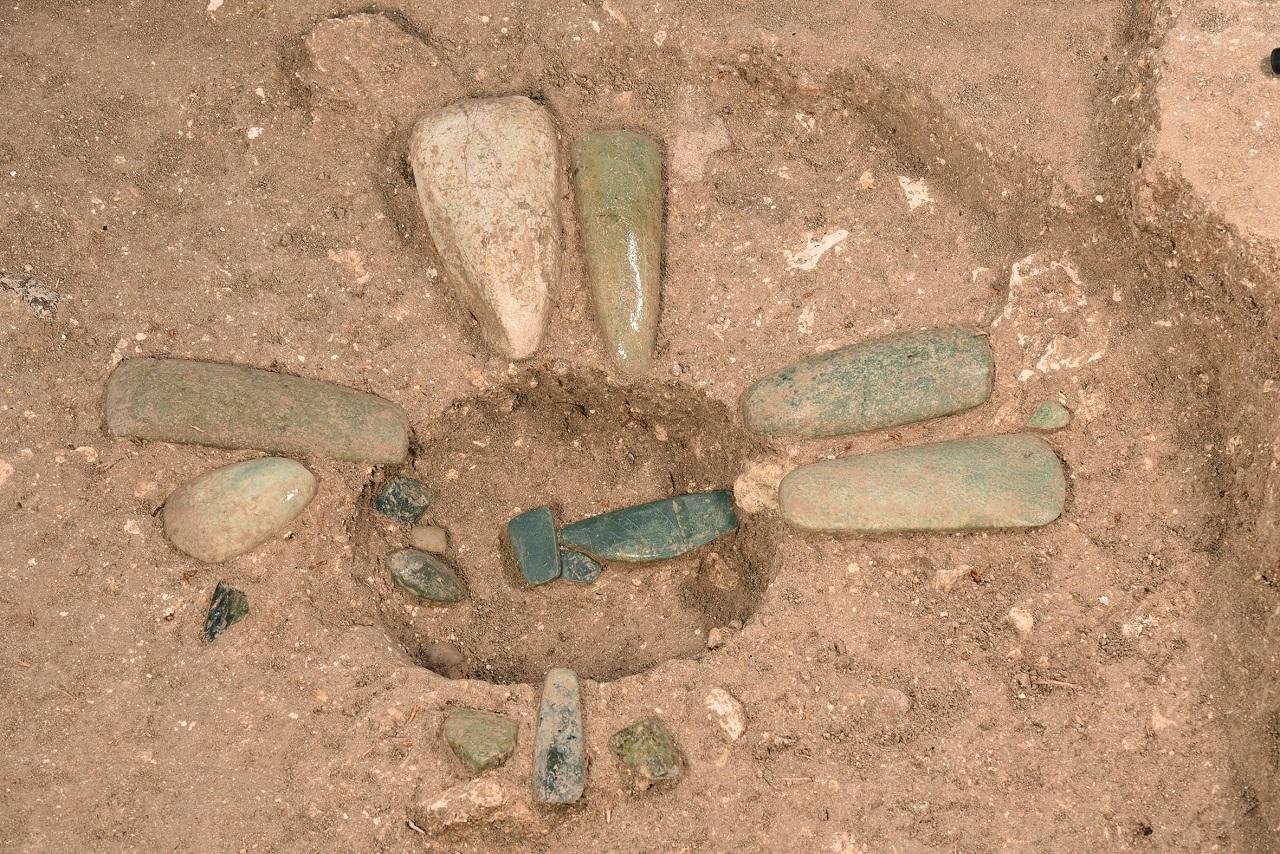

Recent excavations show that Aguada Fénix was much more than an early ceremonial platform—it was a cosmogram, a symbolic representation of the universe. At its center, archaeologists found a cross-shaped pit containing precious jade axes and ornaments carved into forms such as crocodiles, birds, and a woman in childbirth. Beneath those lay a carefully arranged series of blue, green, and yellow pigments representing the four cardinal directions, an early and physical expression of Maya cosmology.

The design of the site also reveals sophisticated astronomical knowledge: the main axis of the monument aligns with the sunrise on October 17 and February 24, dates that divide the 260-day ritual calendar in half. This connection between architecture and celestial movement provides evidence that such complex astronomical and ritual systems were already in place centuries before the rise of Maya kingship.

Aguada Fénix is built entirely out of compacted earth, without stone, and features long causeways, corridors, canals, and a dam that all share the same solar orientation. Radiocarbon dating indicates that construction started around 1000 BCE and that it was used for approximately 300 years as a place of gathering for major communal ceremonies.

Remarkably, there is no trace of any rulers, palaces, or elite residences. Unlike later Maya cities, which were built under centralized authority, Aguada Fénix seems to have been a collective project: a monumental achievement born of cooperation rather than coercion. The archaeologists estimate that more than 1,000 people participated in its construction, contributing seasonal labor during the dry months.

The find has challenged long-held assumptions that social hierarchies were necessary to build large-scale monuments. Instead, Aguada Fénix provides evidence that early Maya communities organized themselves around shared ritual and belief, constructing structures of immense cultural and symbolic significance without kings or forced labor.

This valuable perspective reshapes the way archaeologists understand the origins of Mesoamerican civilization. The builders of Aguada Fénix were fundamentally innovative in using astronomy, ritual symbolism, and communal organization to shape not only their landscape but also their worldview. Their work suggests that monumental achievements can arise from unity and shared vision, not dominance or inequality.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.