According to a recent publication, archaeologists working at the medieval fortress of Zorita de los Canes in central Spain unearthed an unusually striking skeleton: a middle-aged man with an exceptionally long, narrow skull whose remains tell a tale of both a demanding life and a violent death. The subject, unearthed from a cemetery used between the 13th and 15th centuries, may have belonged to the military-religious Order of Calatrava, a group of warrior-monks active at this time.

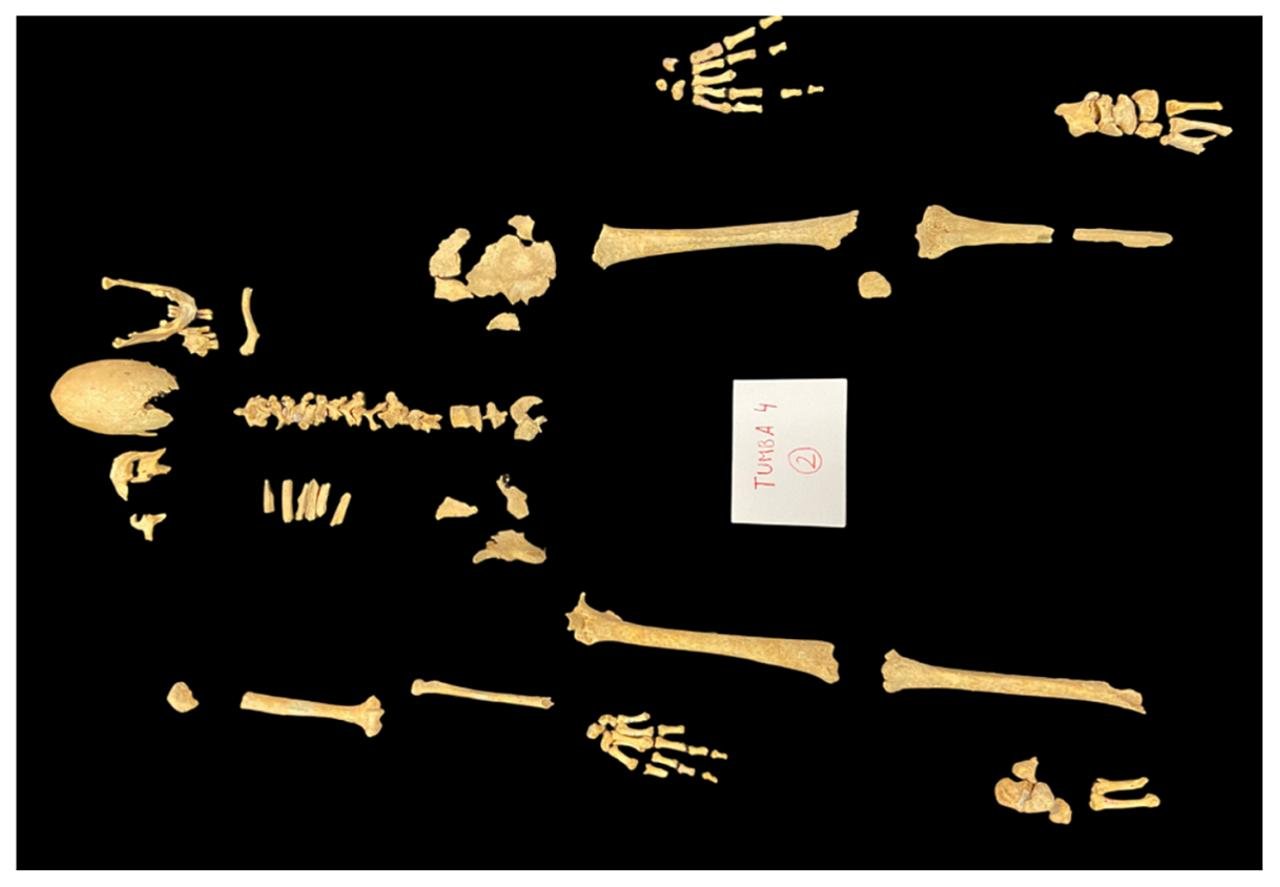

The man’s skull was immediately notable for its extreme elongation. Measurements of 230 millimeters in length and 122 millimeters in width classify it as ultradolichocephalic, well outside normal ranges. Detailed examination revealed that a number of cranial sutures—sagittal, squamosal, and sphenofrontal—had fused prematurely. This condition, called craniosynostosis, interferes with the normal growth of the skull and can place pressure on the developing brain. Nowadays, it can be treated with surgery, but such interventions did not exist in medieval Europe.

The pattern of fused sutures and the narrowed base of the skull suggested a form of syndromic craniosynostosis, probably Crouzon syndrome, caused by genetic mutations affecting the development of the skull and facial features. Other features include a long, projecting lower jaw and an underdeveloped cranial base, although the study notes that only genetic testing could confirm it. Adult cases of the syndrome are extremely rare in an archaeological context because many affected infants in the medieval world would have died in early childhood.

Despite all of these challenges, the man survived well into his mid-to-late 40s. The postcranial skeleton reflects strong muscle attachments and suggests consistent activity. Dental remains reveal a striking contrast between the two sides of the mouth: heavy calculus coating the teeth on the left side and, on the right, tooth loss with minimal build-up that may indicate long-term asymmetry in function or development.

The circumstances of his death appear to have been violent. Two sharp-force injuries—one at the back of the skull and another at the left temple—show no signs of healing, indicating they occurred at or near the moment of death. A blunt-force injury on the left tibia also lacked remodeling. These wounds are consistent with battlefield trauma, similar to injuries found on other men buried in the same cemetery, many of whom are thought to have been Calatrava knights.

This is noteworthy not only because of the condition that it reveals but also due to the life that it implies. Despite a congenital disorder that could have caused serious complications, the man survived decades, and his bones reflect the routine demands of a physically active existence. This combination of cranial deformities, advanced age, and combat-related injuries makes this one of the rarest documented examples of an adult with probable Crouzon syndrome in medieval Europe.

The study marks a remarkable intersection of hereditary disease, long-term survival, and martial identity. It offers a rare view into how someone suffering from an extreme craniofacial condition might have lived and fought within the rigid and often dangerous world of medieval military orders.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.

More more thank you..,