A new study published in the journal Antiquity provides new insight into how anthropomorphic figurines from the Viking Age were produced, used, and eventually deposited. Rather than solely viewing these objects as symbolic depictions of gods, warriors, or other mythological beings, the researchers examined them as material bodies that interacted with people and environments across their life courses.

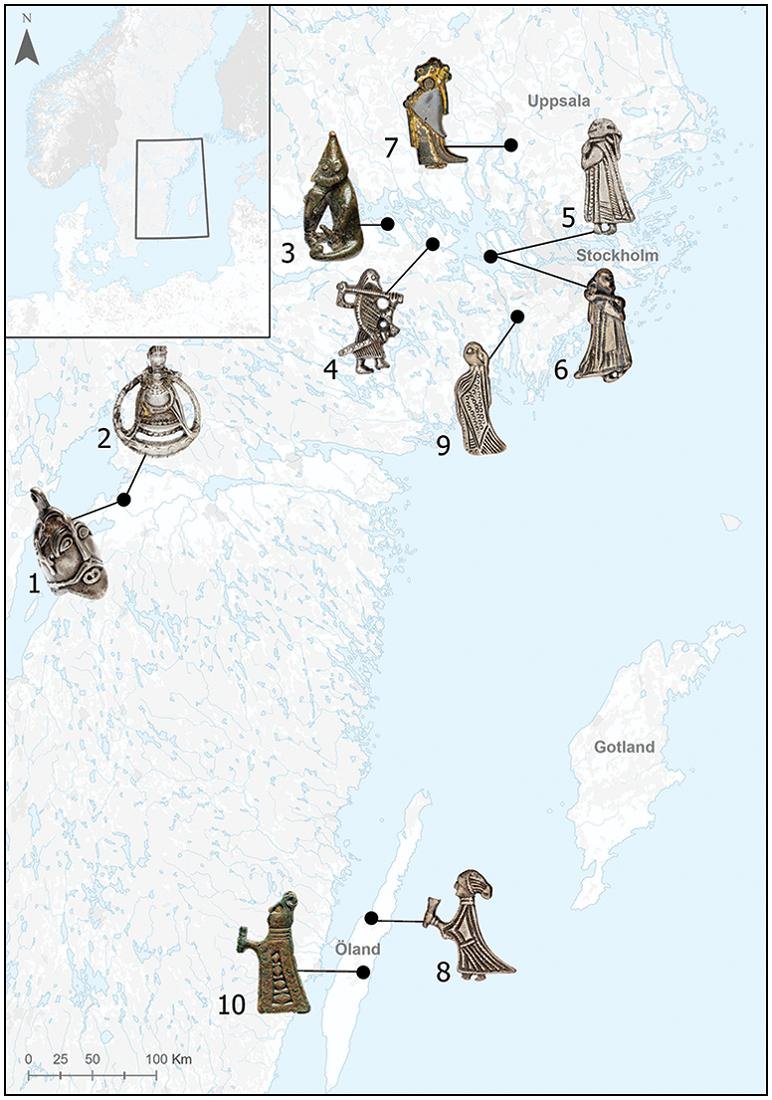

The study focused on ten Viking-Age miniature figurines from Sweden made of bronze or silver, all currently in the collection of the Swedish History Museum. These include the so-called “valkyrie” figures, one seated phallic figure, a rare pregnant form, and a head that was cast separately. To understand how they were handled and altered, the team employed microwear analysis and Reflective Transformation Imaging. These techniques identified surface smoothing, scratches, fractures, and polishing, which enabled them to reconstruct the history of the objects.

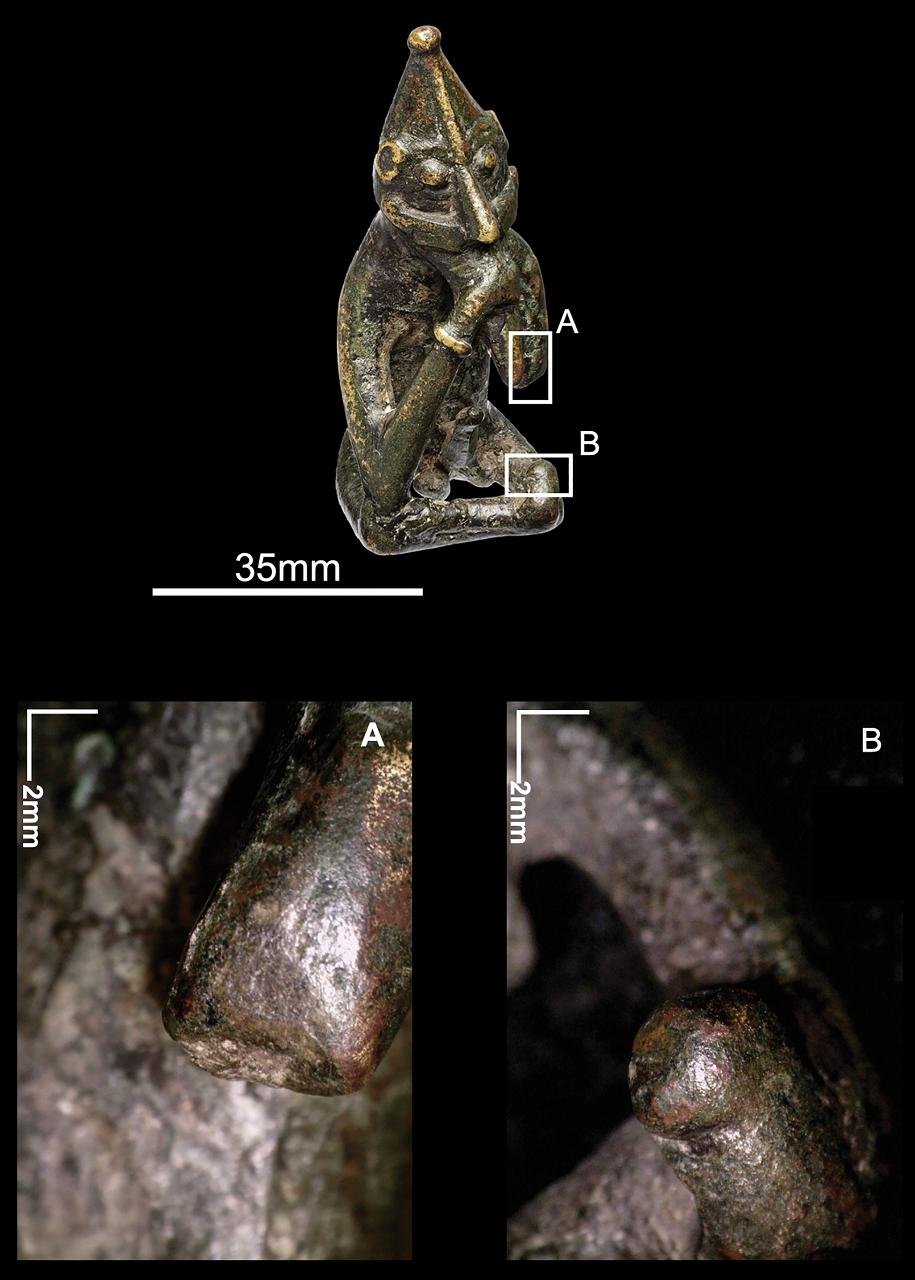

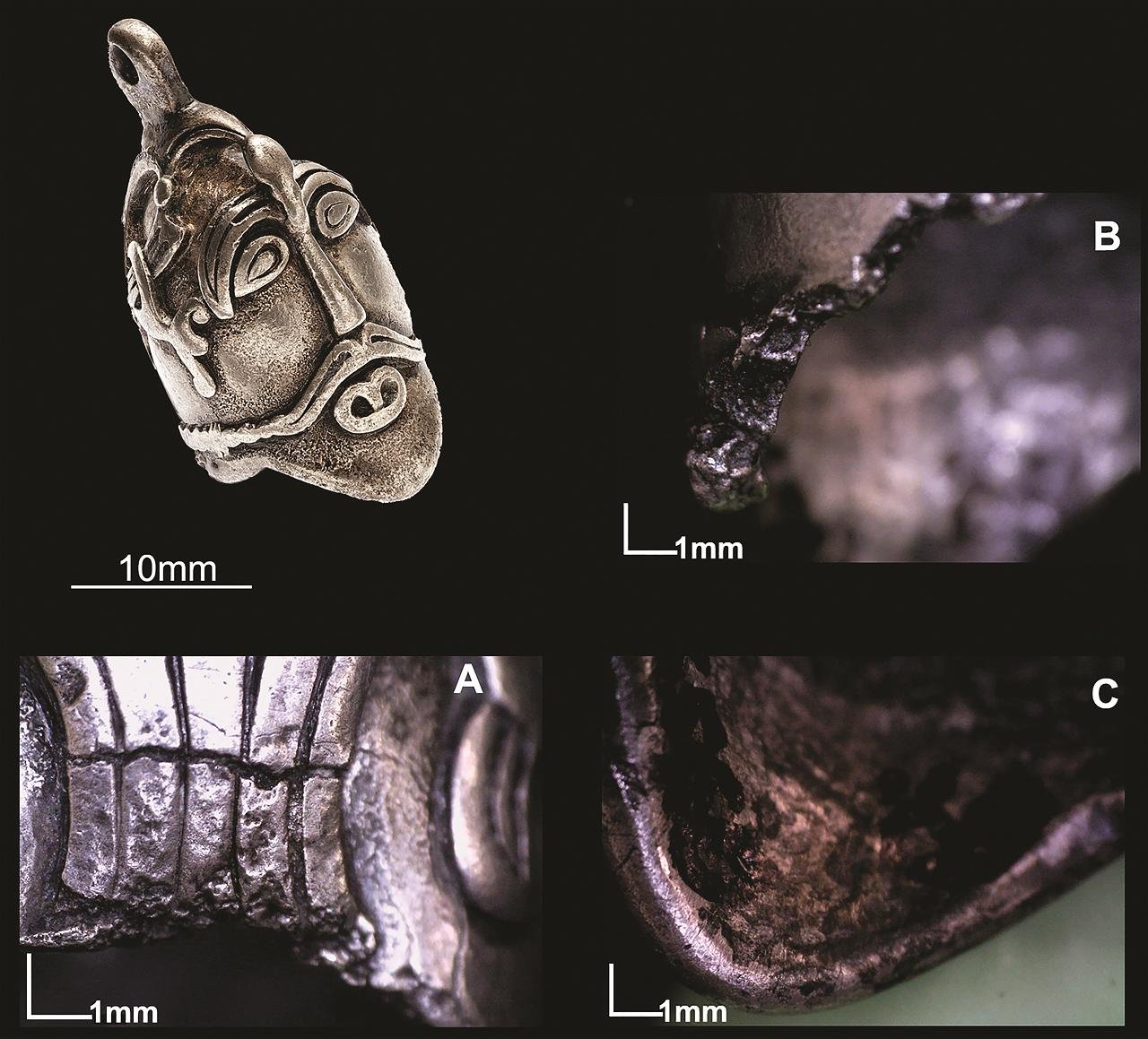

The results demonstrated that many of the figurines had a multistage production process, rather than being formed by a single casting event. Makers cast the metal, then refined, decorated, or reworked different parts, sometimes with uneven detail. This implies that specific features—like garments or weapons—had more importance for their intended function than facial realism.

Nine of the figurines have suspension loops or perforations, indicating that they were designed to be attached to clothing, cords, or other objects. Wear patterns, however, vary considerably: some pieces show heavy rounding that suggests long-term handling or wrapping in fabric, while others remain sharply defined, indicating little use before deposition. This variation suggests that not all figurines circulated in daily life; some may have been created specifically for burial or offering contexts.

Evidence of intentional modification also came to light. The well-known Rällinge figure had its arm broken, and after snapping, the area was smoothed, demonstrating that the object was reshaped after being damaged. The cast head from Aska seems to have been deliberately separated from a larger figurine since percussion marks suggest the removal of the head rather than accidental breakage. Such alterations reflect ongoing engagement with these miniature bodies rather than passive ownership.

The final stages of use of these objects reveal further complexity. Six of the ten pieces were recovered from graves, where they were placed alongside human remains. Others came from hoards or were found as isolated discoveries. These contexts demonstrate that figurines were not simply decorative items; rather, they participated in ritual, identity expression, memory, and mortuary practice.

Emphasizing the traces of use rather than symbolic interpretation, this study challenges established typologies that have classified such objects mainly as amulets, ornaments, or mythological representations. The results indicate that figurines were active participants in the social and ritual life of the Vikings. They were made, worn or carried, sometimes broken or reconfigured, and finally placed in meaningful contexts.

The authors maintain that such objects, understood through their material histories rather than through assumptions based on texts or iconography, offer a more grounded view of how people in the Viking world interacted with the things they created.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.