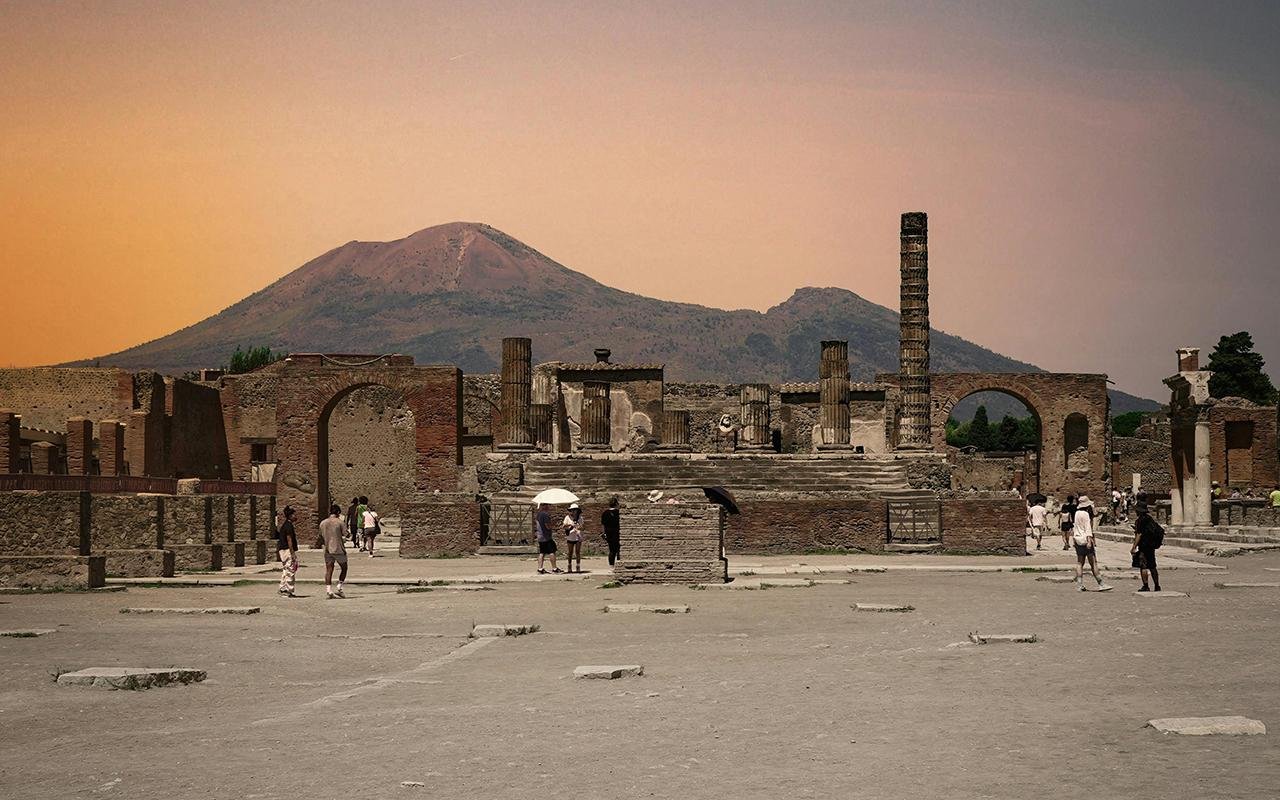

A rare piece of evidence of Roman building practice, frozen in time by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, is revolutionizing current knowledge of ancient concrete. A new study led by researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and published in Nature Communications investigates an incomplete construction site in Pompeii, where Roman engineers were able to produce unusually durable concrete with self-repair properties.

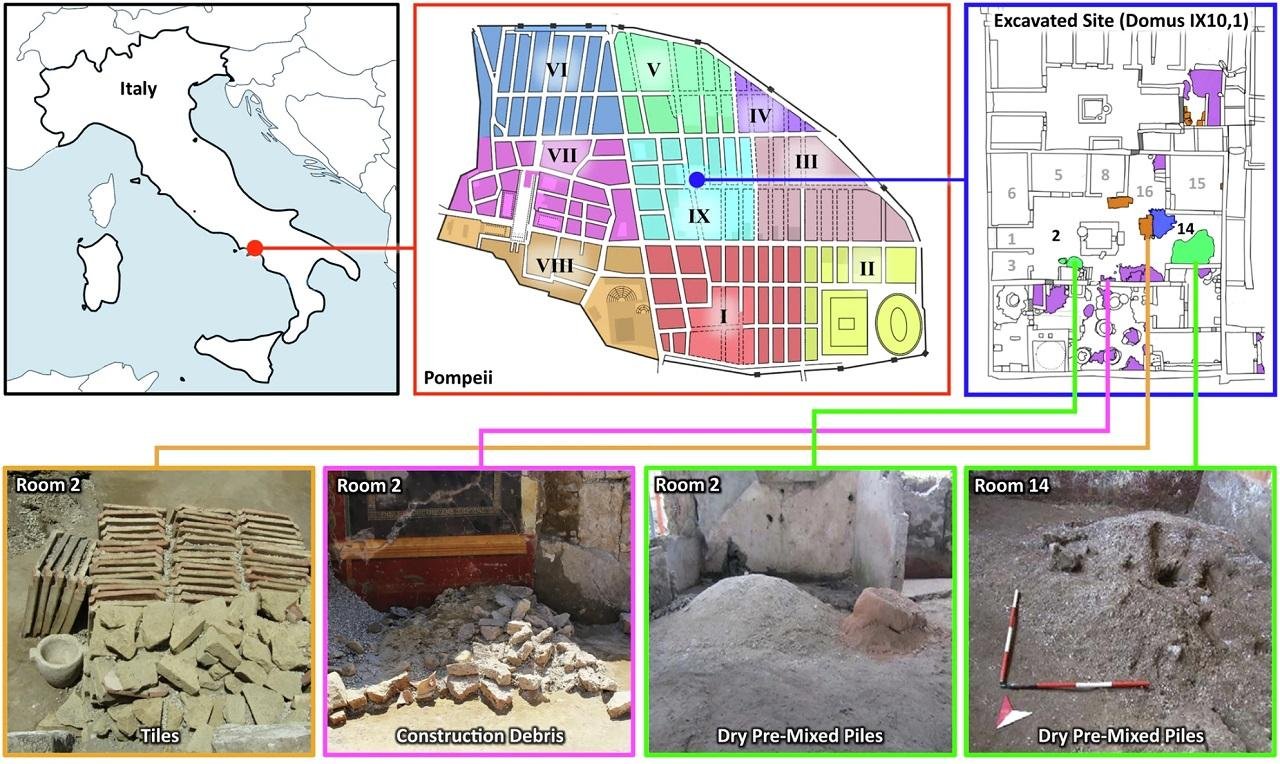

Discovered in Pompeii’s Regio IX, this ancient construction preserves a building in which repairs were underway when the volcano erupted in 79 CE. Builders had left behind stacked tiles prepared for reuse, amphorae used to transport construction materials, masonry tools, and piles of dry construction ingredients ready to be mixed. This combination provided a unique chance to reconstruct the workflow of Roman concrete production, from raw materials to finished walls.

Chemical and microstructural investigations have demonstrated that Roman builders pre-mixed quicklime with a dried volcanic ash known as ‘pozzolana’ before adding water. This process, known as hot mixing, involves an exothermic reaction and produces a high temperature in the mortar. Unlike modern concrete, which is mixed wet from the start, this method produces a distinct internal structure marked by microscopic fragments of partially reacted lime, known as lime clasts.

The presence of these lime clasts in Roman buildings proved to be very important. When cracks form in the hardened concrete and water penetrates the material, the clasts react, and calcium is released to fill these cracks. The study identified reaction rims around volcanic aggregates and evidence of calcium-rich phases such as calcite and aragonite, demonstrating how cracks could gradually heal through mineral growth. Such self-healing in ancient Roman buildings was previously observed in the tomb of Caecilia Metella on the Via Appia, but the Pompeii site gives conclusive evidence of how this capability originated during construction.

The results have also allowed a better understanding of some ancient texts. While Vitruvius described mixing lime with pozzolana, he did not mention hot mixing, which led many scholars to assume a different process. Yet ancient texts written by Pliny the Elder describe the intense heat released when quicklime meets water, which matches closely with what is now identified at Pompeii. The texts and archaeological data suggest that Roman builders experimented with different recipes and techniques, adapting materials to local conditions and structural needs.

However, it is important to note that not all Roman concrete was produced this way. In fact, ancient authors themselves noted that poor-quality mortar caused building failures in Rome. While Pompeii is an example of skilled Roman engineering, it was not a universal rule. Questions remain about how widespread hot mixing was, whether it developed over time, and whether it was a response to frequent earthquakes in the region.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.