A circular stone labyrinth that has been found in the Boramani grasslands in the Solapur district in Maharashtra has been discovered to be the largest in the country. The discovery is not only significant in terms of the size and complexity of the structure but also for what it reveals about the trade routes that linked inland India to the Mediterranean world nearly two thousand years ago.

It is approximately 50 feet by 50 feet in size and has 15 concentric circles formed from small stone blocks. The rings guide movement inward toward a tightly coiled spiral at the center, creating a design that reflects both precision and symbolic intent.

Before this discovery, the largest known circular labyrinth in India had 11 circuits, making the Solapur example unprecedented in terms of circular complexity. Although there is a larger square labyrinth in Tamil Nadu, this newly documented site is the largest circular stone labyrinth identified in the country to date.

The labyrinth was discovered not as the result of excavation but through the work of locals who were part of a conservation group that monitored wildlife within the Boramani grassland sanctuary. This site is famous for harboring creatures such as the Great Indian Bustard and the Indian wolf. After documenting the stone formation, the conservationists alerted archaeologists.

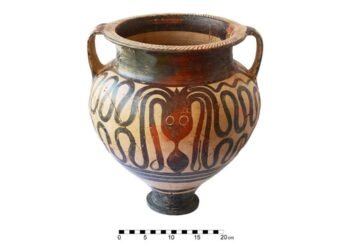

Primary analysis indicates that this labyrinthine structure dates back around 2,000 years, placing it in the Satavahana period, a time characterized by extensive internal and overseas trade. The presence of soil accumulation between the stone rings shows that this structure has remained untouched for several centuries. In fact, its design resembles classical labyrinth forms found in Mediterranean cultures, including motifs seen on Roman-era coins, while also incorporating a central spiral associated in India with the concept of the Chakravyuh.

It is also believed that the labyrinth might be linked to the commercial networks that connected the Deccan region with Roman traders operating along the western coast of India. There is historical evidence that goods such as spices, silk, and indigo were exchanged for gold, wine, and luxury goods, with trade routes extending far inland. Similar labyrinths have also been found in other districts, on a smaller scale, along these routes, suggesting they formed part of a broader cultural landscape shaped by movement, exchange, and interaction.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.