New genetic research from southern Spain is shedding light on how prehistoric monuments retained their significance long after their construction. A recent study examining medieval burials at the Menga dolmen in Antequera, Málaga, reveals that this iconic Neolithic structure continued to play a symbolic role almost four millennia after it was built.

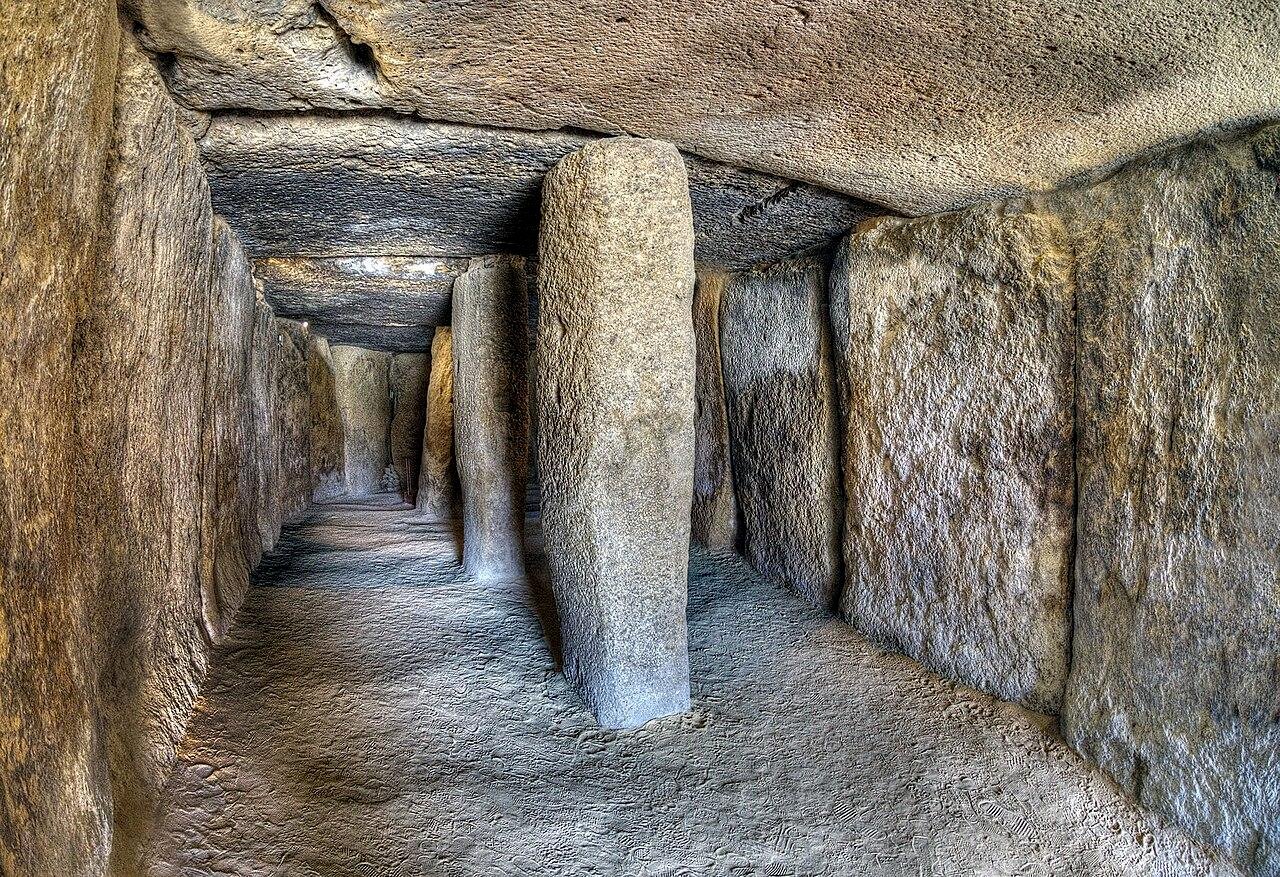

The Menga dolmen, erected around the fourth millennium BCE, is one of the largest and best-known megalithic tombs in Europe today, forming part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site. While it was originally erected as a communal burial monument, archaeological evidence has long suggested that the site was later reused by subsequent societies. The new study, bringing ancient DNA analysis together with archaeology and historical context, provides the clearest picture yet of this later phase.

Researchers focused on two adult individuals found in the dolmen’s atrium during the 2005 excavations. Radiocarbon dating places their burials between the 8th and 11th centuries CE, a time when this region was part of Al-Andalus during the early medieval period. Without grave goods, both individuals were buried face down, with their bodies carefully oriented in relation to the monument’s central axis. This broadly fits Islamic funerary practice; however, the deliberate alignment with the dolmen itself sets these burials apart from typical Islamic cemeteries in the area.

Poor preservation in the Mediterranean climate meant that recovering ancient DNA from the remains proved difficult, and of the two individuals, only one, an adult male, called Menga1, produced genetic data of sufficient quality to analyze. The results, however, were remarkable. His genetic profile reflects a mix of ancestries related to Western Europe, North Africa, and the eastern Mediterranean. While his paternal lineage was common in Europe, aspects of his maternal lineage are closely related to modern North African populations. His ancestry at the genome-wide level resembles that observed in other Iberian individuals of Roman and medieval times, reflecting many hundreds of years of mobility, trade, and migration across the Mediterranean.

These results are in good concordance with historical documents reporting intensive contacts between Iberia, North Africa, and the Levant, particularly during the period following the Islamic expansion into the peninsula in the early 8th century. Simultaneously, however, the study emphasizes that genetic ancestry cannot be equated directly with religious or cultural identity.

More than individual origins, the research highlights the persistence of the relevance of the Menga dolmen itself. The reutilization of such a monumental prehistoric structure implies that medieval communities did not consider it simply to be an ancient ruin. Similar examples of reuse in other parts of the Iberian Peninsula demonstrate that megalithic monuments may have been reused as burial sites during the Islamic period, possibly because they were perceived as sacred, powerful, or linked to ancestral memory.

Rather than being a point of termination in prehistory, the Menga dolmen emerges as a locale with an extremely long biography. Genetics, archaeology, and history together indicate how it is possible for sacred landscapes to transcend cultures and religions, remaining meaningful across thousands of years.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.

It deserves a visit since I live in Portugal… what I don’t know is if it’s accessible for people like me…