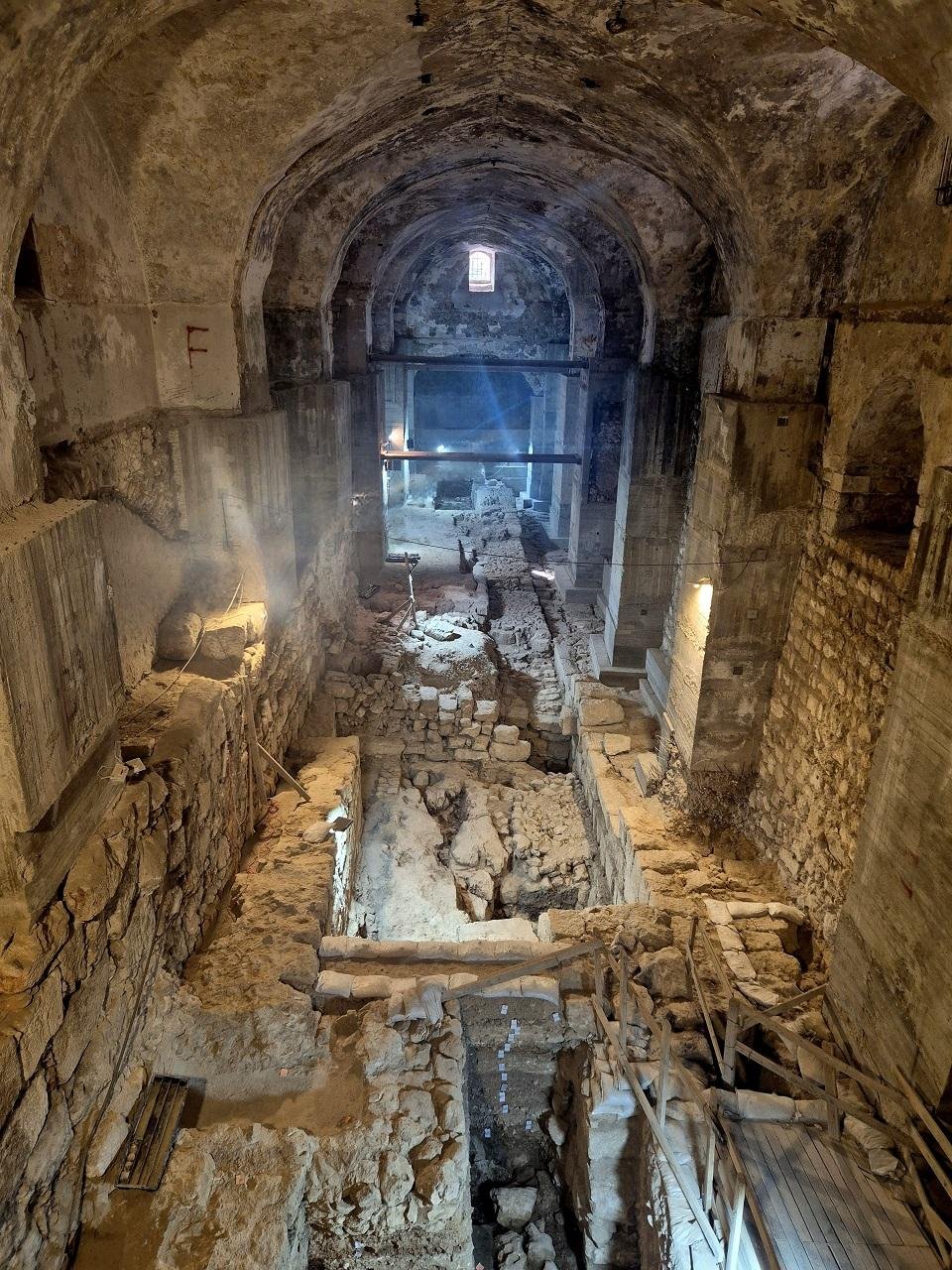

Archaeologists in Jerusalem completed the exposure of a remarkably well-preserved segment of a city wall dating to the late 2nd century BCE, in the Hasmonean-Maccabean period. Unearthed within the Kishle complex at the Tower of David, adjacent to the historic citadel, it represents one of the longest and most intact fortification sections ever found within the city. Excavation work was done by the IAA as part of preparations for the future Schulich Wing of Archaeology, Art, and Innovation at the Tower of David Jerusalem Museum.

The newly uncovered wall is identified with the so-called “First Wall” familiar from ancient historical sources. Well over 40 meters long and about five meters wide, the fortification was built from massive stone blocks that were finely dressed with a distinctive chiseled boss, typical of the Hasmonean period.

Researchers believe the wall stood over ten meters high in its original state. Similar sections of the defensive system have been uncovered around Mount Zion, the City of David, the courtyard of the citadel, and along parts of the western boundary of Jerusalem, but none is as extensive or as well-preserved.

The first-century CE ancient historian Josephus described this city wall as a powerful and almost impregnable defense, reinforced by dozens of towers. Archaeological evidence from the Kishle, however, suggests that this wall did not simply disintegrate over time. Rather, remains suggest deliberate and systematic dismantling, raising questions as to who ordered its destruction and why.

Researchers propose two different historical scenarios. One explanation links the demolition of the wall to events surrounding the Seleucid siege of Jerusalem by Antiochus VII Sidetes in the 130s BCE. Historical sources tell of how the Hasmonean ruler John Hyrcanus I negotiated an agreement to end the siege, which might have entailed the removal of Jerusalem’s fortifications as one of the conditions of peace. The section of the dismantled wall may constitute the physical evidence of that political compromise.

One alternative possibility places responsibility decades later, during the reign of King Herod. In seeking to distance himself from the Hasmonean dynasty that he supplanted, Herod might have deliberately erased their monumental building projects. The systematic nature of the wall’s destruction is consistent with broader Herodian policies aimed at reshaping Jerusalem’s urban and political landscape.

Excavations nearby give further context to the turbulent period in which the wall stood. In the 1980s, archaeologists discovered a large cache of Hellenistic weapons at the foot of the First Wall: catapult stones, arrowheads, slingstones, and lead projectiles. This is generally interpreted as remnants of the failed assault of Antiochus VII, with heavy siege weapons accumulating at the foot of defenses they could not breach.

The exposed wall will remain as the centerpiece of the new wing of the museum, with the stones to be viewed from above through a glass floor. The project aims to integrate archaeology with contemporary artistic interpretation in such a way that allows the public to engage in a direct and tangible encounter with the ancient defenses.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.