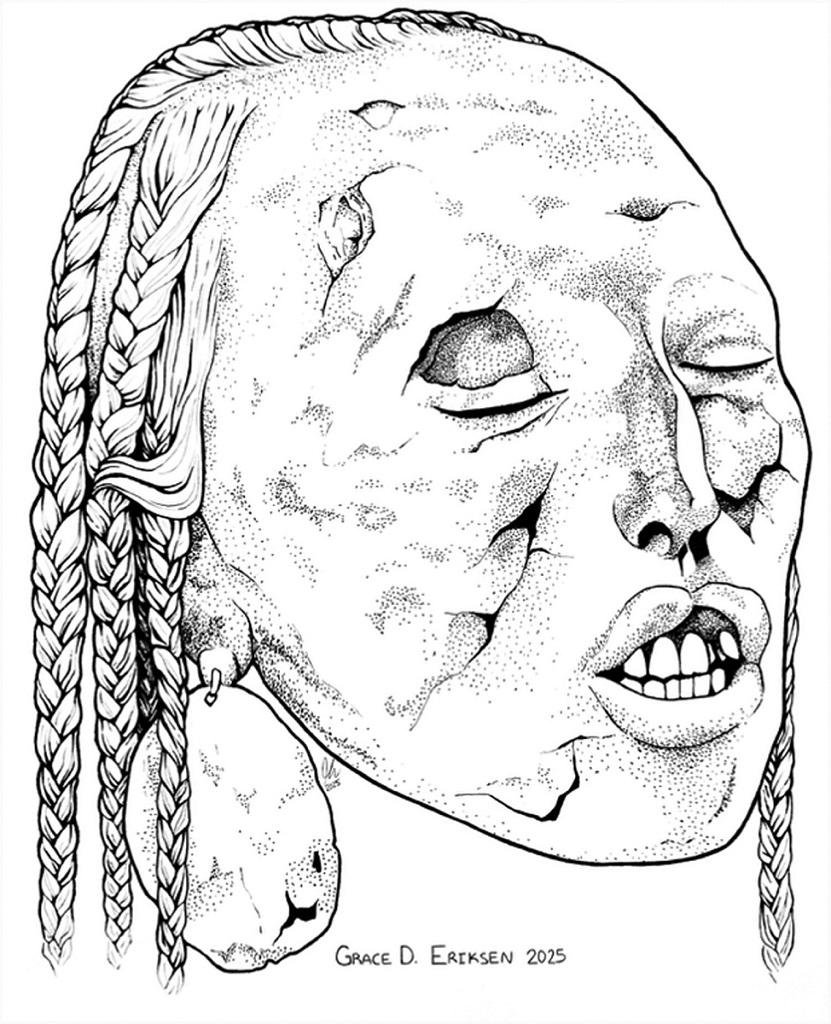

A newly analyzed Andean trophy head from southern Peru is providing new insight into how ancient societies viewed individuals with congenital conditions. Based on photographs in museum catalogs, researchers identified a definitive case of cleft lip and palate (CLP) in a mummified head currently housed in France. It is the first known example of CLP in an Andean trophy head and one of only a few confirmed instances in human remains throughout the region.

Trophy heads, carefully prepared, decapitated human remains, have long been a part of Andean ritual practice. They were collected in warfare, ancestor veneration, and ceremonies that treated the head as a powerful object. Many ended up, over the centuries, in private collections and museums, often with very little documentation. This head was listed in a 2021 exhibit catalog, its origins traced to the Paracas region on Peru’s southern coast. It features a glossy, amber-toned patina and copper earrings, suggesting special treatment in life and after death.

The photographs suggest that the individual was a young adult male with a unilateral cleft affecting the left side of his mouth. Though CLP can sometimes make it difficult to feed during infancy, thus challenging survival to adulthood, he still survived to adulthood. That already puts him in a rare group, as only a few examples of long-lived CLP are known from Andean archaeological contexts.

This case is compared with 30 ceramic vessels showing people with similar facial differences. Such vessels, created in northern Peru and southern Ecuador, illustrate individuals in elite clothing or engaged in ritual activities. Together with early colonial accounts, they indicate that individuals born with CLP frequently had priestly or spiritually important roles. Instead of the stigmatization of congenital facial differences, many Andean societies seem to have regarded them as markers of supernatural protection or sacred power.

In this wider cultural context, the status of this individual is a key question. The braiding of the hair, preserved earrings, and the attention paid to the preparation of the trophy suggest that this was an important person. Even the presence of the cleft may have influenced the preparation of the head, as the usual method for closing the mouth with cactus spines would have been impossible on one side.

Genetic studies and modern medical records in Peru indicate that CLP has ancient roots, especially in coastal regions. Environmental stressors—such as high-altitude hypoxia or exposure to alcohol during pregnancy—may have shaped ancient patterns of CLP occurrence. Often, Andean cosmologies explained congenital conditions as the result of specific maternal experiences during pregnancy. These explanations are comparable to modern understandings of stress and environmental factors influencing fetal development.

Since the study relies on photographs, not a complete physical examination, many details remain speculative. Direct examination of the skull, DNA testing, and isotopic studies of the hair and bones could help tell a more specific story about the individual’s sex, diet, health, and origins. Yet the present case provides a unique opportunity to explore how ancient Andean people treated, interpreted, and honored those born with physical differences.

The trophy head offers more than an anatomical diagnosis. It highlights how cultural perspectives on disability, identity, and sacredness interacted, revealing a world in which a congenital facial condition may have elevated, rather than marginalized, an individual in life and death.

Comments 0