Archaeologists have identified a tool dating to around 500,000 years ago made from elephant bone, at the Boxgrove site in southern England, which presents the oldest known tool made of elephant bone in Europe. The fragment, with dimensions reaching 11 cm in length, 6 cm in width, and 3 cm in thickness, shows signs of having been used repeatedly as a soft hammer for refining stone tools. Analysis using 3D scanning and electron microscopy revealed embedded flint fragments and impact marks, which indicate it was used as a retoucher, a tool used to resharpen and shape stone handaxes and other items made of flint.

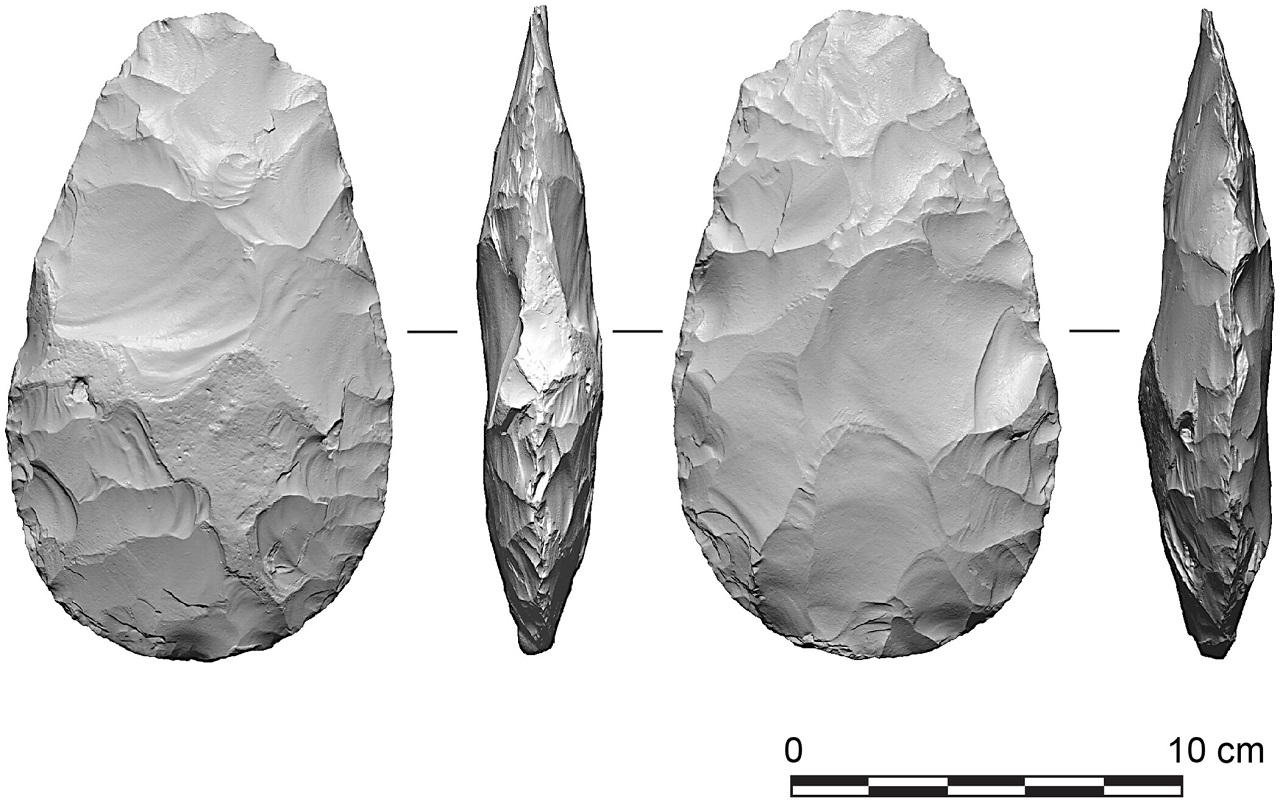

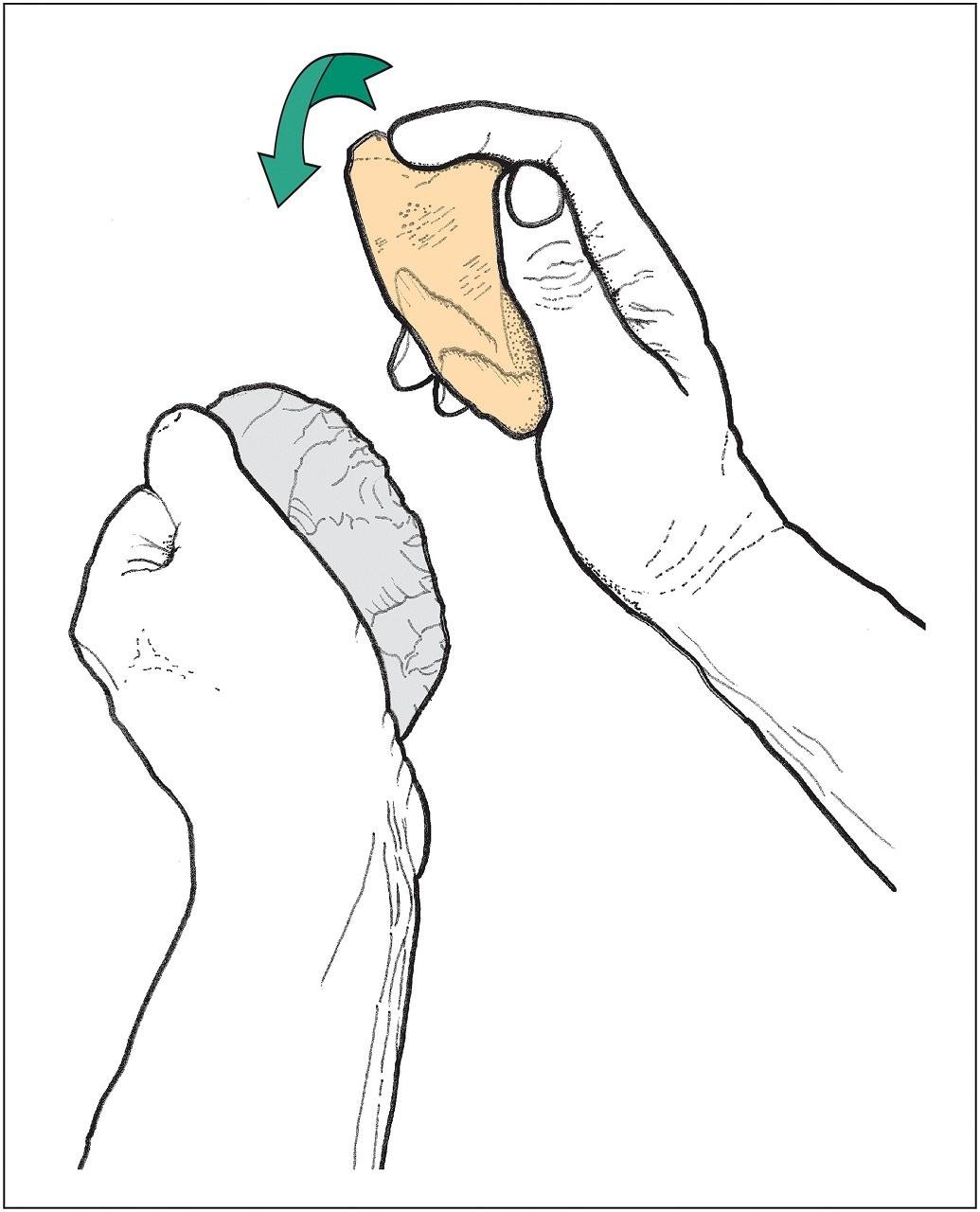

The Boxgrove site has yielded much evidence of Lower Palaeolithic human activities, but this fragment of elephant bone is exceptional. The dense cortical tissue of the bone made it particularly suitable for delicate knapping tasks, offering more precise control than stone hammers. The precision enabled the shaping of highly symmetrical handaxes, which are characteristic of later phases of the Acheulean industry at Boxgrove, showing sharper edges and greater refinement than those found at other sites in Eurasia.

This discovery also demonstrates the technological planning abilities and sophistication of Middle Pleistocene hominins. The selection of elephant bone also demonstrates an appreciation for material properties and access to scarce resources. These species, mammoths and elephants, were uncommon in southern England, and no other elephant remains were found at Boxgrove, meaning that this bone was intentionally brought to the site for tool production. The tool’s modification while the bone was still relatively fresh points to deliberate preparation rather than opportunistic use.

The hominins to whom this tool belonged are also not known with certainty, with both Homo heidelbergensis and Neanderthals being likely candidates. Their ability to employ soft hammers and retouchers reflects advanced cognitive skills, including planning, abstract thinking, and technological foresight. The use of organic tools such as bone, antler, and wood alongside flint hammers facilitated complex knapping techniques, including platform preparation and tranchet flake removal, enabling the production of refined ovate handaxes.

Comparative evidence indicates that elephant-bone tools existed in East Africa as early as 1.5 million years ago, but European examples older than 43,000 years are rare, with the majority from warmer southern regions. The Boxgrove tool proves that advanced lithic strategies spread to higher latitudes during the Lower Palaeolithic, pointing to the ability of humans to survive in challenging northern climates. It also raises questions about the distribution of technological knowledge across prehistoric populations in Europe.

The example of the Boxgrove elephant-bone retoucher shows the ingenuity of early humans. By selecting durable, scarce materials and employing them to enhance the efficiency of stone tool production, these hominins achieved a level of craftsmanship previously unrecognized in northern Europe. The study also provides insight into Middle Pleistocene toolkits and the role of organic materials in the development of refined Acheulean technologies.

The research, published in Science Advances, highlights both the preservation challenges of organic tools and their significance in reconstructing the behavioral and technological capabilities of early human populations.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.