Archaeological research from the Templo Mayor Project offers new evidence for the long-debated practice of animal captivity in the ancient Mexica capital of Tenochtitlan. The study focuses on zoological remains recovered from ritual offerings linked to the Huei Teocalli, the main ceremonial complex dedicated to Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc. Tenochtitlan stood on an artificial island within Lake Texcoco, at the location of present-day central Mexico City, and functioned as the political and religious center of the Mexica state.

The research examines 28 animal skeletons recovered from eight offerings. The identified species include golden eagle, harpy eagle, quail, jaguar, wolf, and roseate spoonbill. Archaeologist Israel Elizalde Méndez conducted a detailed paleopathological study of the bones, focusing on joint degeneration, healed fractures, infections, and stress related skeletal markers. Such conditions allow reconstruction of living conditions experienced by each animal before ritual use.

Many skeletons display advanced joint disease, severe infections, and healed traumatic injuries. Several of these pathologies would have limited movement, hunting ability, or flight. Survival under wild conditions with such impairments appears unlikely. Sustained human care, controlled feeding, and confinement provide a stronger explanation for the observed bone changes. Dietary residue analysis from birds of prey supports regular provisioning with prepared food rather than hunting.

These findings support historical accounts describing an animal enclosure within Tenochtitlan, often called the Totocalli. Spanish sources from the early sixteenth century mention a facility housing birds, large predators, and aquatic species. Archaeological excavation within the presumed area remains limited due to dense urban development, and no architectural remains of such an enclosure have been identified. Osteological evidence from the Templo Mayor offers indirect support for captive management described in early colonial texts.

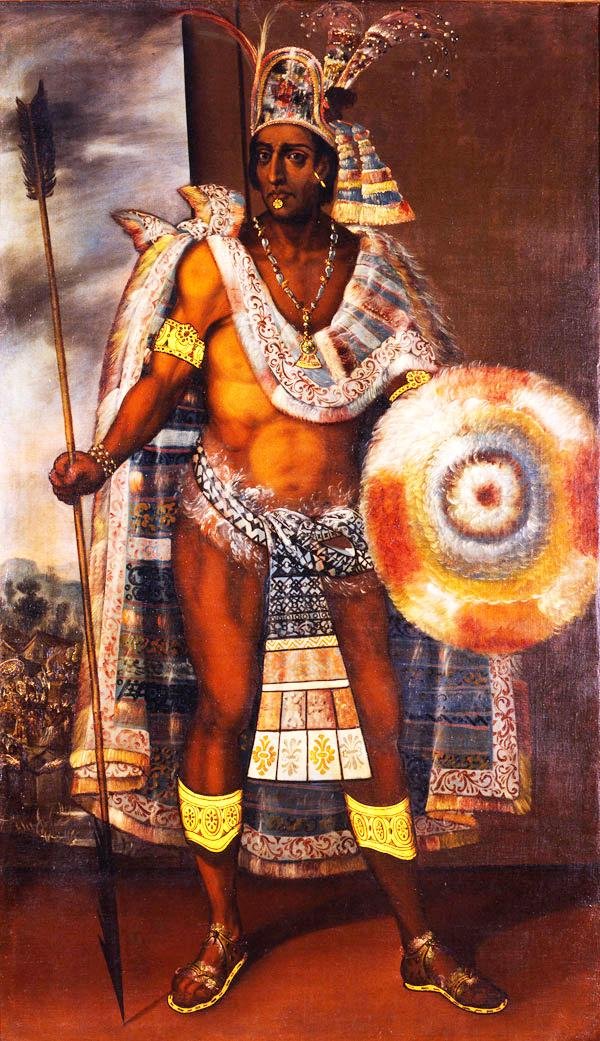

A map of Tenochtitlan attributed to Hernán Cortés place the animal enclosure behind the sacred precinct near the royal palace. The recovered animals come from offerings dated to the Late Postclassic period, consistent with the reign of Moctezuma II. Evidence from wolves suggests controlled breeding, which implies long term planning and specialized care. The presence of aquatic birds such as roseate spoonbills aligns with descriptions of an aviary linked to water symbolism.

Within Mexica religious thought, animals held defined roles connected to cosmic order. Birds represented the sky, aquatic species symbolized water, and terrestrial predators reflected the earth. Ritual offerings required living representatives of these domains. Maintaining animals inside the city before sacrifice reinforced religious authority and ritual precision. Captivity therefore served a ceremonial purpose rather than public display.

The study presents a methodological framework for identifying captivity in pre-Hispanic contexts through bone pathology and contextual analysis. Results strengthen the interpretation of organized animal management within Tenochtitlan and place animal care at the center of Mexica ritual practice.

More information: INAH

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.