Archaeologists in Saxony-Anhalt uncovered a narrow underground passage during excavations near Reinstedt in the Harz district. Fieldwork took place ahead of the planned construction of wind turbines on a low-rise known as Dornberg. The team from the State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology (LDA) first identified a large trapezoidal ditch belonging to the Baalberge culture, a Middle Neolithic group active in central Germany during the fourth millennium BCE.

Earlier activity already marked the area as a burial landscape. Excavators recorded poorly preserved crouched graves from the Late Neolithic and traces of a possible Bronze Age burial mound. Within the southern stretch of the Baalberge ditch, archaeologists noticed an elongated oval pit about two meters long and up to 75 centimeters wide. A heavy stone slab rested near one end, which at first suggested a grave feature.

Closer excavation showed a different picture. The pit fill sloped downward toward the north and continued deep into compact loess soil inside the Neolithic enclosure. Late medieval pottery fragments appeared in the fill along with many stones. Small cavities survived in the upper layers. These clues pointed to a later underground construction known as an Erdstall, a type of man-made tunnel system found across parts of Europe, often in firm soils such as loess.

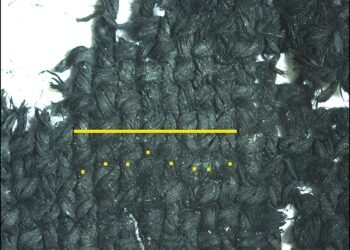

Removal of soil in the northern section revealed a tight passage curving northwest. The corridor measured between roughly one meter and 1.25 meters in height and only 50 to 70 centimeters in width. Parts of the سقroof showed a pointed, gabled form carved from the surrounding soil. A carved step marked the entrance zone, and a small wall niche appeared along one side.

Finds inside the passage included an iron horseshoe, the skeleton of a fox, and numerous bones from small mammals. At the lowest level, excavators documented a thin charcoal layer. Surrounding soil showed hardening but no reddening, which suggests a brief, low-intensity fire rather than a long-burning hearth. Near the tightest point of the entrance, several large stones had been stacked together. Such placement indicates deliberate blocking of access at some stage.

Erdstall tunnels vary in layout, though most share narrow passages and concealed entrances. Scholars have proposed several functions, including temporary refuges during unrest, storage spaces, or locations linked to ritual practice. The Reinstedt example stands out because medieval builders inserted the tunnel into a prehistoric monument. The visible earthwork of the Neolithic ditch may have served as a landmark in the landscape, making the entrance easier to relocate.

Another possibility relates to local beliefs about ancient burial grounds. Sites linked with pre-Christian graves often carried a reputation for danger or taboo during the Middle Ages. Limited everyday traffic in such areas would have offered privacy for anyone seeking a hidden space. Ongoing analysis of finds and soil layers will refine the chronology of use and blocking phases within the tunnel.

The discovery adds a rare stratified example of an Erdstall connected directly to a well-dated prehistoric enclosure. Such associations provide valuable context for studying construction methods, reuse of ancient monuments, and patterns of medieval activity in rural central Germany.

More information: State Office for Monument Preservation and Archaeology Saxony-Anhalt

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.

Historical footprints need to be protected