A new study examines how divine sanctuaries fit into medical practice in ancient Mesopotamia. Troels Arbøll analyzed cuneiform prescriptions from the second and first millennia BCE and found a small group of texts that direct patients to visit the sanctuary of a god before further treatment. The findings appear in the journal Iraq.

Temples rarely appear in surviving medical tablets. Healers known as asû and āšipu usually worked outside temple institutions, especially in earlier periods. Out of a large body of medical material, Arbøll identified only 12 prescriptions across six manuscripts that include instructions to seek a sanctuary. This limited number makes each reference important for understanding how religious practice intersected with healing.

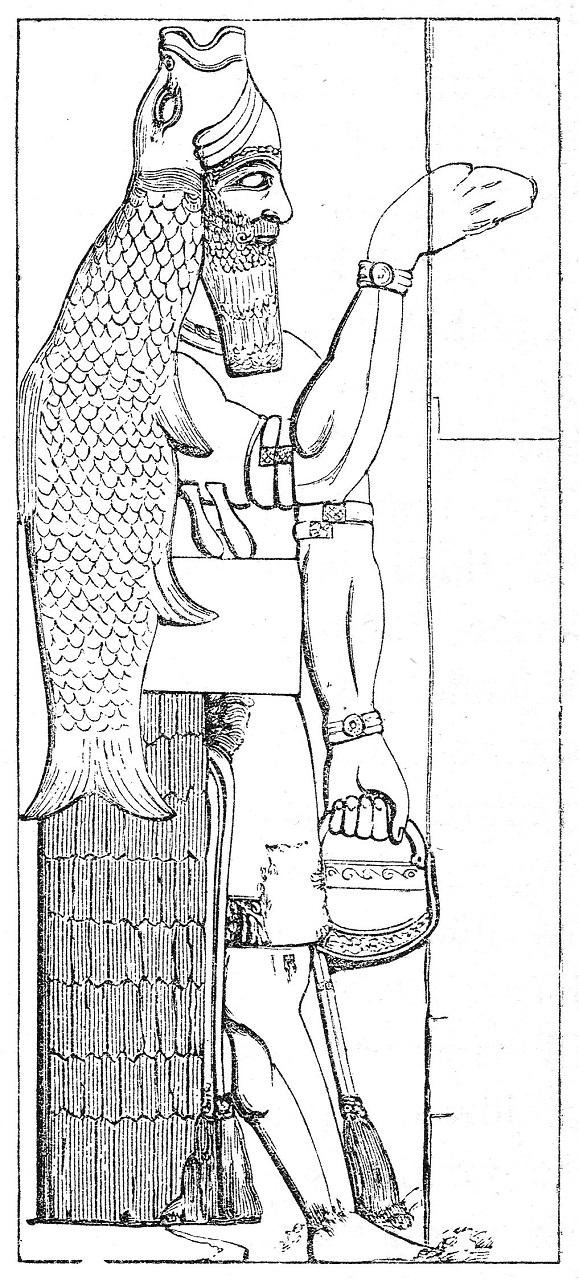

Five of the six manuscripts concern diseases of the ear. The sixth addresses disorders of an organ called ṭulīmu, often linked to the spleen or pancreas. In these cases, the prescription tells the patient to go to a sanctuary of a named deity such as Sîn, Ninurta, Šamaš, Ištar, or Marduk. The term used for sanctuary, aširtu, might refer to a large temple complex or a smaller local or private shrine, possibly inside a home.

The visit formed part of the therapeutic sequence. After reaching the sanctuary, the patient likely recited prayers and performed rituals. Offerings may have been presented. Archaeological finds support this pattern. At the temple of the healing goddess Gula in Isin, excavators uncovered votive figurines linked to illness and recovery. Such objects suggest that sufferers brought items representing their condition and left them as appeals for relief.

The texts state that the patient sought to “see good fortune,” a phrase that points to reversing bad omens tied to disease. Illness in Mesopotamian thought carried prognostic meaning, and unfavorable signs could affect the success of treatment. Gaining good fortune before applying drugs or rituals by a healer appears to have improved the expected outcome.

Several prescriptions mention a period of six days linked to this favorable state. The wording allows two readings, either the sixth day or six days in duration. Arbøll argues that a span of days fits better with instructions in the same texts that repeat treatments over multiple days. The count may have started from the sanctuary visit, from the onset of symptoms, or from formal diagnosis. The tablets do not resolve this detail.

Why ear and ṭulīmu disorders required sanctuary visits remains uncertain. Mesopotamian sources connect the ear with hearing, attention, and obedience, traits tied to receiving divine messages. Ear infections also posed clear medical risks. They could lead to dizziness, severe pain, and extended confinement to bed. In serious cases, infection could spread and threaten life. Such dangers may have prompted extra ritual steps.

A newly identified manuscript from Hama in Syria adds another example of this instruction, strengthening the pattern. The study suggests that sanctuary visits helped patients avoid inauspicious days and reset their prospects before therapy began. These actions did not replace the healer’s work but preceded it.

The evidence shows that temples did not dominate Mesopotamian medicine, yet selective cases called for divine favor as part of care. By assembling scattered references, the study clarifies how ritual movement between home, shrine, and healer shaped treatment for specific illnesses.

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.