Archaeological excavations at Parco delle Acacie in the Pietralata district of eastern Rome have revealed a long and complex history of settlement outside the ancient city walls. Work led by the Special Superintendency of Rome documents activity from the fifth or fourth century BCE through the first century CE, with weaker traces during the second and third centuries CE. The results challenge older views of Rome’s eastern outskirts as marginal zones with limited historical depth.

The investigation began during the summer of 2022 as part of preventive archaeology connected to an urban development program. Excavations across roughly four hectares exposed an area of concentrated remains covering about one hectare. At the center of this context lies an ancient road aligned northwest to southeast, laid across terrain shaped by a watercourse flowing toward the Aniene River. One stretch of the route near Via di Pietralata consisted of compacted earth, while another section closer to Via Feronia was cut directly into tuff bedrock. Cart ruts preserved in the rock surface point to sustained traffic during the Republican period. Formal construction along this axis started during the third century BCE with a large retaining wall built of tuff blocks, replaced a century later by masonry in opus incertum. During the first century CE, new paving and flanking walls in opus reticulatum kept the route in use until gradual abandonment, marked by modest pit graves dating to the second and third centuries CE.

Along this road stood a small quadrangular sacellum measuring about 4.5 by 5.5 meters. The building featured walls in tuff opus incertum with traces of interior plaster. A square plastered base aligned with the entrance served as an altar, while a rear projection likely supported a cult statue. Excavation beneath the structure exposed a disused votive deposit with terracotta heads, feet, female figurines, and two bovine figures. Combined with the site’s position near the Via Tiburtina, these finds link the shrine to the cult of Hercules, a protective deity widely honored in Republican Rome. Bronze coins date construction of the sacellum to the late third or second century BCE.

Nearby, a single funerary complex contained two elite chamber tombs accessed through parallel corridors. Tomb A, dated to the fourth or early third century BCE, held a peperino sarcophagus and three cremation urns, accompanied by fine ceramic vessels, black glazed cups, and a bronze mirror. Tomb B, probably slightly later, contained benches for inhumation and the remains of an adult male skull bearing evidence of surgical trepanation. The scale and architecture of both tombs point to ownership by a wealthy Roman gens controlling this territory during the Republican era.

The most imposing features at the site are two monumental basins. The eastern basin measured about 28 by 10 meters and reached a depth of just over two meters. Built during the second century BCE in opus incertum, the structure included vaulted niches, a dolium set into concrete, and a ramp descending partway into the interior. Channels supplied water from the nearby stream and hillside. Architectural terracottas and inscribed ceramic fragments recovered from the fill suggest ritual activity, although productive functions also receive consideration. Decline began during the first century CE, with final closure by the end of the second century.

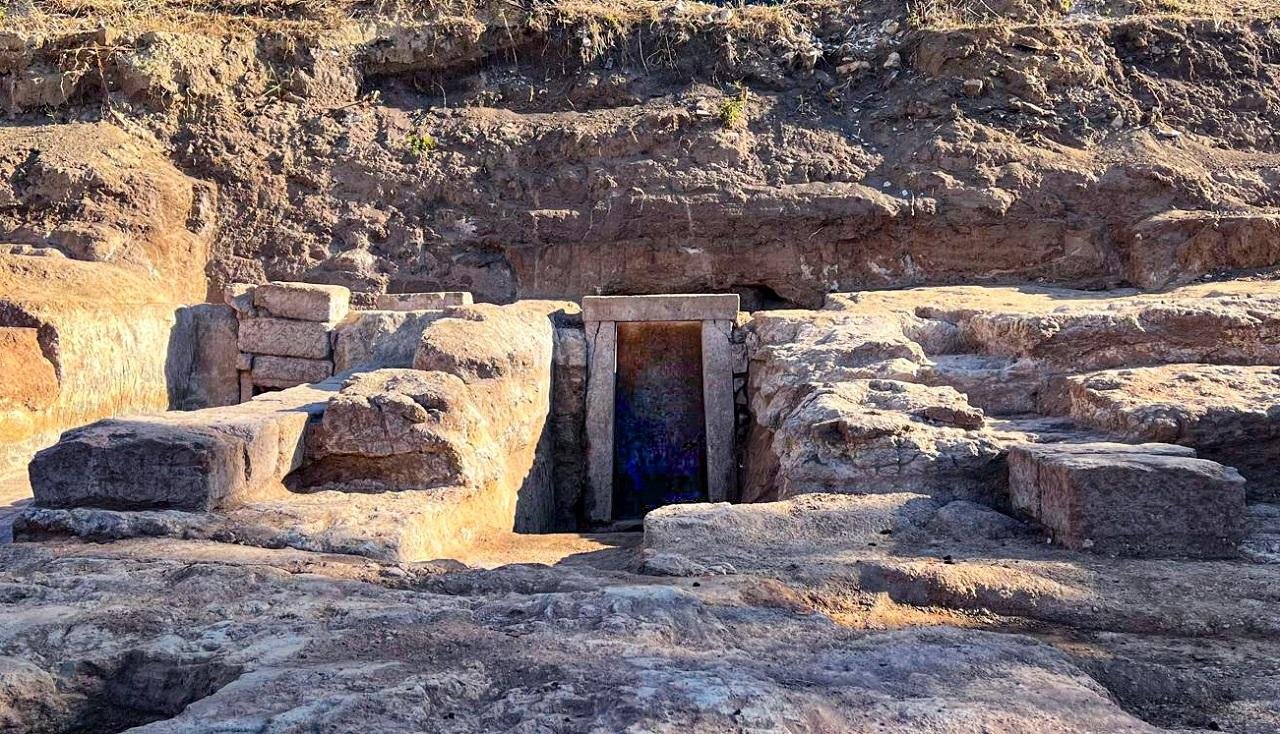

A second basin to the south was cut directly into tuff bedrock and reached a depth of about four meters. Walls of squared blocks lined the exterior, with later additions in opus reticulatum and opus quadratum. Access involved two descending ramps paved with large stone blocks and concrete slabs. No clear inlet or outlet channels have appeared, leaving function unresolved. Similarities with a third century BCE basin excavated at Gabii, interpreted as sacred, support a ritual explanation. Ceramic material within the fill places abandonment during the second century CE.

Together, the road, shrine, tombs, and basins portray Pietralata as an active zone shaped by ritual, burial, movement, and water management across several centuries. Continued study aims to integrate these findings into a broader understanding of Rome as a dispersed city whose growth relied on peripheral areas as much as on monumental centers.

More information: Italian Ministry of Culture

Disclaimer: This website is a science-focused magazine that welcomes both academic and non-academic audiences. Comments are written by users and may include personal opinions or unverified claims. They do not necessarily reflect the views of our editorial team or rely on scientific evidence.

Comment Policy: We kindly ask all commenters to engage respectfully. Comments that contain offensive, insulting, degrading, discriminatory, or racist content will be automatically removed.